1

What to Do and Why

Four Contemporary Views on Development

One day Alice came to a fork in the road and saw a Cheshire cat in a tree. “Which road do I take?” she asked. “Where do you want to go?” was his response. “I don’t know,” Alice answered. “Then,” said the cat, “it doesn’t matter.”

Lewis Carroll, Alice in Wonderland

Always be prepared to give an answer to everyone who asks you to give the reason for the hope that you have. But do this with gentleness and respect.

1 Peter 3:15

One thing I’ve learned is how important worldviews are. We must learn to evaluate worldviews, because they are so basic to what people do in life.

Hayden Hill, development worker in East Africa, 2007–9

An Illustrative Case

There are some things in development work that everyone agrees on. Children dying for lack of food is absolutely unacceptable. Young people being trafficked for sexual slavery is a terrible violation of human dignity that must be stopped. We cannot stand by when child soldiers, senses deadened by drugs and violence, are taught to torture and kill. Reckless and environmentally destructive deforestation cannot be tolerated. Christians, Muslims, liberals, and conservatives all agree on the above points. Agreement becomes much more difficult, however, when we try to identify the causes behind the world’s pain and determine exactly what must be done to fight evil and promote the good.

Economist Jeffrey Sachs, one of today’s most prominent development thinkers, argues in The End of Poverty that development is a lot like health and poverty a lot like sickness. He likens development workers to doctors who diagnose problems before treating them. Sachs points out that the symptoms of illness (fever, pain, listlessness) and the symptoms of unhealthy societies (hunger, infant mortality, violence) are indications of deeper maladies that must be diagnosed accurately before being treated. This is a helpful point, but there is another issue that Sachs does not address. He seems to assume that all doctors have the same understanding of health. He does not mention how significant which school of medicine the doctor attended is in determining the approach taken for treatment (e.g., medical, osteopathic, chiropractic, homeopathic). Just like in medicine, in development too there are distinct, prominent, and competing theoretical schools where today’s development “doctors” go for training. Depending on which school development workers attend, they will understand human development in distinct ways and will treat recognized diseases quite differently. In deference to the famous Cheshire cat, if we want to know what road to take, we must know where we want to go and how we want to get there.

Consider the following story and ask yourself what the malady is, what the causes are, and what treatment would be most effective:

You would probably need more information to have complete confidence in your diagnosis, but based on what you know, what do you see as the problems, and what treatment plan would you recommend? To spur your thinking, here are four ideas.

A The basic cause is poverty, which is in turn caused by the lack of access to functioning markets. Therefore, we should encourage Chabekum and/or Babul either to start a business by joining the loan group or to migrate to Dhaka to look for jobs.

B The basic cause is that Chabekum and Babul are oppressed and powerless, so we should help them organize protest movements that can fight against injustices like Babul’s land being taken away.

C The basic cause is that foreigners come in with all their strange ideas and their NGOs and mess things up. It would be best to leave Babul and Chabekum to work things out in the context of their own culture, their own beliefs, and their own ways of life.

D The basic cause is that Babul and Chabekum are both so beaten down that they cannot participate in making choices about their own future. We should help provide education, food, and health services, as well as protect their rights, so that they can participate and decide for themselves what will make their lives better.

You probably noted right away that this question is like those on annoying college tests that seem to offer several good answers for each question, all of which you could reasonably mark down as being the best one. You might also notice that some possible good answers are missing. Why, for example, are gender issues left unmentioned when they seem to be a big part of Chabekum’s distress? How about the role of faith? Maybe they are plagued by disempowering religious beliefs. But you are left to guess which answer your professor prefers. Personally, I hate when that happens. Those tests are supposed to be “objective,” but so much depends on one’s perspective.

In this case, the question and answer are not “objective” in the least, because the “best” answer would definitely depend on your professor’s views on development. If your professor were a modernizationist, the answer would be A; if a dependency theorist, then B; if from the postdevelopment school, C; and if a proponent of the capabilities approach, then D would be the best answer.

Four Contemporary Perspectives on International Development

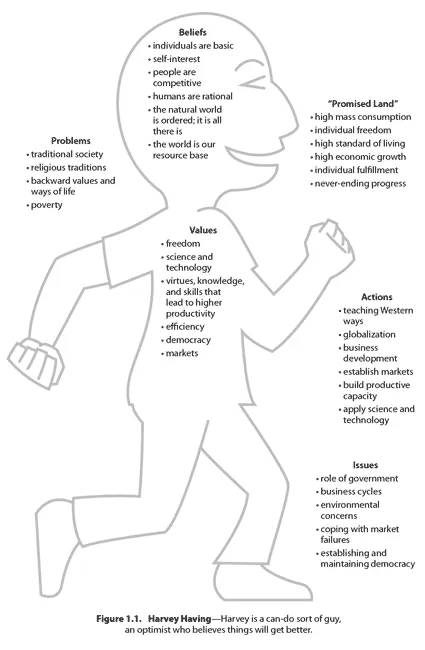

These are the four secular perspectives that dominate the world of development thought and practice today. Each is thoughtful and reasonable, and each is associated with distinct ways of engaging in development work. To help us understand these views and prepare the way for thinking about development in a Christian context in chapters 2 and 3, I will summarize these four perspectives by highlighting key features of their particular ways of thinking. In each case, I personify the perspective with a character whose name may help you remember the big ideas. Get ready to meet Harvey Having, Libby Liberating, Betty Being, and Charles Choosing. Each person/perspective we encounter here is complex and multifaceted, with many surprising and subtle traits, but I will resist doing a deep psychoanalysis of each one. As you are introduced, ask yourself whether you like them and whether you would like to attend the same development school where they are professors.

Modernization—Meet Harvey Having

Harvey is an optimistic, cheerful, can-do sort of fellow from the modernization school. What really motivates him is a high standard of living and the freedom to enjoy life. When you have access to goods and services, you can do the things that bring joy to your life. If you have food, then you can eat; a boat, and you can go sailing; a book, and you can read; a car, and you can travel. Services are also important. Harvey can go to school to learn a productive skill, thus giving him the potential of higher income in the future. If his income allows it, Harvey can hire others to do things he would rather not do himself, like mow his lawn or do his taxes, thus giving him more time for leisure activities. Having goods and services raises the standard of living, extends life expectancy, and generally makes life more enjoyable.

For modernizationists there is a synergistic relationship between economic well-being and individual freedom, so much so that Harvey sometimes wonders which comes first and which is more important. Harvey will debate this with his friends, but the happy conclusion is that they generally go together.

Harvey grew up in the West where he and others like him have a lot more stuff than their ancestors did. How much more is measured by the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita. Harvey looks back and sees how far he and his nation have come; he thinks that if poor countries want to change for the better, they must follow in the tracks of the West. Just as Harvey and his forebears worked their way to progress, poor countries can also overcome their poverty by expanding individual freedom, becoming more productive, and generating economic growth.

If we want to help poor nations develop, we must learn the lessons of wealth creation in successful societies. Thankfully, Western democratic capitalist societies are blessed with a several-hundred-year history of discovering the secrets of wealth creation, so what the poor really need to do is learn these secrets and put them into action. If poor countries want to be rich, then they must build market economies and structure their politics, families, personal values, and ways of life around the characteristics of successful market economies. These are comprised of individual property rights; personal freedom; an entrepreneurial culture; limited government; private markets; reliance on science, technology, and industry; and openness to trade and finance on global markets.

If Harvey were to feel a call to development work, what could he do to help? There are any number of ways, but they can all be boiled down to helping poor nations become more like Western societies while also helping them integrate into the global market system. Here are a few typical strategies:

Teach Western ways of medicine.

Teach about and help structure private markets so they are well regulated but free from unhelpful government interference.

Promote Western business practices through teaching and mentoring.

Provide investment capital for major industrial investments as well as the microenterprise and small- and medium-business sectors.

Educate children to read and to love math and science and to adopt such Western values as punctuality, competitiveness, and a need for achievement.

Teach productive skills, such as agriculture or urban trades.

Influence political and justice systems to be more democratic and fair.

Teach Western values such as responsibility, saving, stewardship of property, and respect for private property through religious and cultural missions.

Were Harvey to advise Babul and Chabekum, he might encourage them to apply Western business practices in their local settings (financial lending, investment, production, sales), which could be achieved through a microfinance/microenterprise program like the one the NGO is offering. It would also be reasonable to suggest migrating to the city and working in a factory that is integrated into the global market. As developing economies industrialize, it is natural and important for poor rural people to migrate to the cities in search of work. Either of these two strategies takes advantage of markets to generate higher incomes that allow them to buy food and medicine and further their education in ways that make them ever more productive. Babul and Chabekum will thus take some first steps onto what Jeffrey Sachs calls the “ladder of development.” If they use their higher incomes to send their children to school, the children’s productivity in the future will outstrip that of their parents, and they will climb still higher up the ladder.

To reach these conclusions, beliefs and values matter a great deal. Many of the modernizationist’s foundational beliefs originate in Enlightenment philosophies that center on individual freedom, to the point that individuals decide on their own what their purposes in life are. Because science cannot tell us what the ultimate destination of life is or why we are here, and because religion is seen as a vestige from primitive, superstitious societies, persons decide for themselves what brings happiness. That is why freedom from government or religious imposition is so highly valued.

Some modernizationists, especially the economists, believe that humans are by nature highly self-interested and competitive. Other modernizationists, including Lawrence Harrison, believe people must (and can) be taught to be like this. Ideally, through something like Adam Smith’s famous “invisible hand,” self-interested individuals in competition are necessary foundations of harmonious, democratic, peaceful, and wealthy societies in which standards of living are high for everyone and in which progressively higher standards of living are achieved by every new generation. In a memorable phrase, W. W. Rostow, one of the early modernizationists, identified the goal of development to be a “high mass consumption society.”

Lest you think modernizationists have everything figured out, they are fully aware that there is still much to be learned and that there are many life problems yet to be addressed. For example, they are still working on the best way for governments and markets to complement each other and how to resolve growing environmental issues, harmonize individual striving with social harmony, distribute foreign aid and development assistance, initiate business growth in developing countries, avoid financial crises, and ensure adequate and low-cost health care for everyone. None of this is easy, but the broad outlines of the good society and how to achieve it are nevertheless clear. Harvey is happy and optimistic in part because no other way of organizing society has come close to achieving the wealth of Western market societies but also because, as problems arise, he is confident that rational, scientifically and technologically inclined people will solve them.

I have drawn a sketch of Harvey (see fig. 1.1) that may help you remember some of his key characteristics. As with the other persons we will meet in the next few pages, beliefs are assigned to the head, values are located in the heart region, actions are associated with the hands, and issues are what Harvey walks through to get to the “promised land” of development. Notice that Harvey is walking away from what he understands to be life’s major problems and toward what he sees as progress.

Dependency Theory—Meet Libby Liberating

For many years the strongest challenger to modernization came out of the intellectual tradition of Marxism, a philosophy of life and society that arose as a reaction to the failings of the economic system that Karl Marx called “capitalism.” Marx, a German, witnessed the same horrible consequences of industrialization that his English contemporary Charles Dickens did (e.g., workhouses for the poor, people being forced into the cities and the mills through the enclosure movement, etc.). Instead of writing novels depicting the horror, however, Marx created a whole philosophy of social and economic progress. At the root of Marx’s ideas, which were also rooted in Enlightenment thinking, is the notion of human beings as workers, as persons who can make things to improve their own lives. This quality is what distinguishes humans from other animals. As human history unfolds, it is our ability to work that leads to the oppression of some people by others, as those with power look for ways to take what weaker people make. Over time, however, it is this same aspect of human character that will one day lead to liberation for everyone from both material want and exploitation.

To see how this history proceeds, think of poor people in traditional societies. If hunting and gathering are no longer enough, they can build plows to farm. Having enough food allows the pursuit of other constructive projects such as making fishing equipment, writing books, and making medicines. Such pursuits allow humans to gradually beat back the material limitations of life in an ever-improving, ever-evolving process. For Marx, the expansion of production through the use of technology and science was a part of the process, but his goal was not just to have more stuff; it was for humans to use the products of their hands to become better people, to be liberated for what they might become.

Such progress would come through historical evolutio...