1

Historical Geography

A close reading of the biblical materials makes it possible to establish some aspects of the spatial perspective of the Hebrew prophets. However, since very few modern readers of the Bible have an intimate knowledge of the historical geography of the ancient Near East, it is important to begin this survey of the world of the Hebrew prophets with a brief examination of the topography and climate of these lands. Keep in mind that when the prophets mention a geographic site or feature, they are generally describing a place that they and their audience know intimately. They have walked over each field, climbed the nearby hills, seen the foliage, and smelled the various aromas associated with herding sheep or with cultivating an olive orchard or vineyard. Because their frame of reference is that of a geographic insider, they do not have to go into great detail to conjure up a picture in the minds of their listeners. And because ancient Canaan is a relatively small place, certain place-names or landmarks will reappear over and over again in the text. Even at that, modern readers often become lost amid the strange-sounding place-names and descriptions of places that are either unknown or so foreign that they cannot even be imagined. In order to acquaint modern readers with this unfamiliar world, I provide here a basic description of the major geographic regions of the ancient Near East and their significance to the Israelites. Additional comments on geography or climate, when necessary to describe the words of a particular prophet, will be given in each chapter.

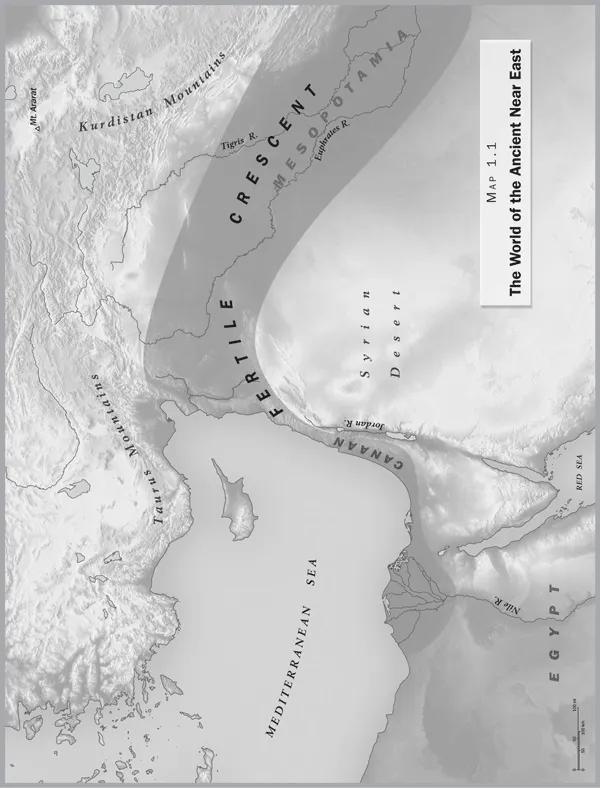

The ancient Near East can be divided into three primary areas: Mesopotamia (modern Iraq), Egypt, and Syria-Palestine. Adjacent to these regions are the Anatolian Peninsula (modern Turkey), Persia (modern Iran), and the island of Cyprus. Each of these subsidiary areas will figure into the history and the development of Near Eastern cultures during the biblical period. For instance, the Hittite Empire in Anatolia and portions of Syria and northern Mesopotamia provided a firm cultural link to the Indo-European nations of Europe and also influenced the political development of Syria-Palestine just prior to the emergence of the Israelites in Canaan. Cyprus and the Syrian seaport city of Ugarit functioned as early economic links with the burgeoning Mediterranean civilizations based on Crete and in southern Greece during the second millennium. For example, the epic literature from Ugarit (dating to 1600–1200) provides many linguistic and thematic parallels to the biblical psalms and the prophetic materials. The island of Cyprus, located just off the western coast of northern Syria, was also a prime source of copper, a metal essential to the technology of the Near East for much of its early history. Finally, Persia developed in the sixth century into the greatest of the Near Eastern empires just as the Israelites were emerging from their Mesopotamian exile. Persian religion (Zoroastrianism) and administrative innovations, including coined money, would contribute to the development of the postexilic community and Judaism both in the Diaspora and in the new Persian province named Yehud, centered on Jerusalem.

Travel between and within the various segments of the ancient Near East and the eastern Mediterranean required a willingness to face the dangers of the road, political cooperation among nations, and technological advancements that allowed for heavier loads. Early shipping hugged the coasts, but by 2000 ships were making regular stops at the Mediterranean islands as well as up and down the coasts of the Red Sea, Persian Gulf, and Indian Ocean. Evidence for such far-flung travel can be seen in the list of luxury items and manufactured goods found in Mesopotamian and Egyptian records and in the speeches of the Hebrew prophets (e.g., the depiction of the Phoenician port city of Tyre in Ezek. 28:11–19).

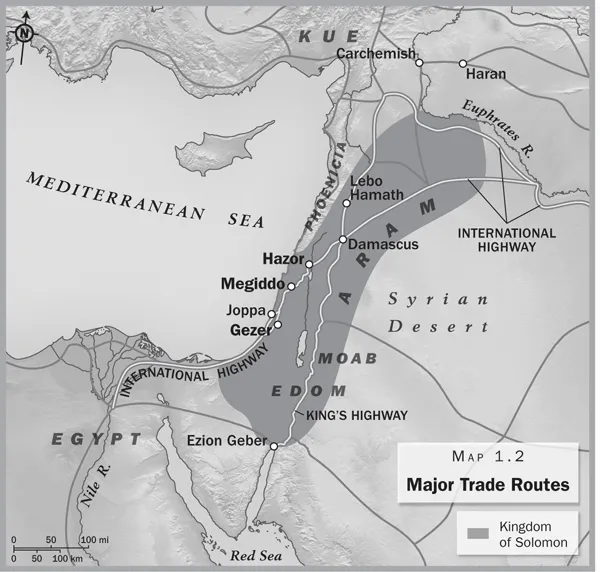

Overland trade routes generally gravitated toward the coasts, where seaports (Tyre, Sidon, Aqaba) could take raw materials and grain to far-flung markets. In Syria-Palestine, two highways linked Mesopotamia and Syria to the Palestinian coast and on to Egypt: the Via Maris and its extension, the Way of the Philistines, which provided a coastal route; and the King’s Highway, which extended from Palmyra to Damascus and south through Transjordan to the Gulf of Aqaba. Caravan routes also followed the Arabian coastline and made it possible for traders to carry frankincense, myrrh, and other exotic goods (ivory, gold, animal skins) from Africa and India up the Red Sea and into the heart of the Near Eastern civilizations.

Mesopotamia

The Tigris-Euphrates River valley is the dominant feature in the area known as Mesopotamia. Today this region contains the nation of Iraq and parts of Iran and Syria. The dual river system flows over an increasingly flat expanse of land as it travels from north to south. There is little rainfall in much of this land, but the melting snows in the mountains of eastern Turkey feed the rivers. Life therefore was often precarious, dependent on the little rain that fell and the volume of water available from rivers and wells. In fact, the river system comprises a vast floodplain that could be inundated when water overflowed the riverbanks. Disaster also could strike very quickly in such a fragile environment, where life-giving winds and rain could be replaced by the drying effects of the desert wind, the sirocco. The epic literature of this land attests to the inhabitant’s dependence on water sources and the capricious character of their gods: “Enlil prepares the dust storm, and the people of Ur mourn. He withholds the rain from the land, and the people of Ur mourn. He delays the winds that water the crops of Sumer, and the people of Ur mourn. He gives the winds that dry the land their orders, and the people of Ur mourn” (“Laments for Ur,” OTPar 252).

Given these environmental conditions, cities and towns could be established only close to the rivers, and only the introduction of massive irrigation projects made possible population growth and an increase in arable land. The cooperative efforts necessary to construct and maintain irrigation systems eventually served as a major factor in the political development of the region. City-states and monarchies appeared very early in Mesopotamian history, while the formation of empires encompassing all or most of Mesopotamia did not occur until the eighteenth century.

No major geographic features provide natural barriers or defenses for Mesopotamia. As a result, waves of invasions by new peoples and the rise and fall of civilizations mark the history of the entire area from as early as 4000. The land also lacked an abundance of natural resources. What forests may have existed in antiquity did not survive into historical times. Mineral resources were found to the north and east of the Tigris-Euphrates valley, but less so within it. To make up for their lack of natural resources, the city-states of Mesopotamia established a brisk river trade to transport goods and large quantities of grain downriver very early in their history. The Mesopotamians also sent caravans into the Arabian Peninsula and east into Persia and the Indus valley of northwestern India. Such widespread trade links brought a further degree of cultural mixing and created a more cosmopolitan culture.

The first civilizations to appear in Mesopotamia were in the extreme southern area and became known as Sumer (ca. 4000). These people took advantage of the wetlands and trade links associated with the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers as they flowed into the Persian Gulf. The city-states of Ur, Kish, Lagash, Nippur, and Uruk dominated this region and were responsible for the invention of the cuneiform writing system, the development of complex irrigation systems, the use of ziggurat towers as part of their temple complexes for their many gods, and the development of strong monarchies, although not empires.

Invaders from the steppes of Central Asia brought the first Semitic culture into the area around 2500. This also led to a spread of the population north into the region known as Babylonia. Babylon, located at the point where the Tigris and Euphrates almost meet as they travel south from the Caucasus Mountains, became the center of this new culture and eventually formed the seat of one of the first Mesopotamian empires, led by Hammurabi (1796–1750).

The Old Babylonian Empire did not survive for long, however. Hammurabi’s successors were weak: they were plagued by a corrupt or complacent military, or the ever-present danger of natural disaster could damage an administration and leave it open to the next wave of invaders. Thus, from 1500 to 1000, no nation or city-state was able to dominate the whole area. Instead smaller kingdoms such as the Mitanni in northern Mesopotamia and the Hittite Empire in Anatolia controlled portions of the area. This fragmentation ended with the rise of the Neo-Assyrians about 1000, who occupied the northern reaches of the Tigris River. They took advantage of the petty kingdoms too busy fighting among themselves to resist an organized and ruthless opponent. Gradually, by 800, Assyrian hegemony came to dominate all of Mesopotamia and then expanded west to the Mediterranean Sea. At its height in 663 the Neo-Assyrian kings were even able to briefly conquer Egypt. In this case, an empire of this size, stretching across more than 1,000 miles and many different geographic regions, was held together by a policy of systematic terror and immediate retaliation for acts of rebellion: “The hunter cut open the wombs of the pregnant. He blinded infants. He slit the throats of warriors. . . . Whoever offended Ashur was executed. Sing of the power of Assyria, Ashur the strong, who goes forth to battle” (“Annals of Tiglath-pileser I,” OTPar 166; compare 2 Kings 8:12; Hosea 13:16). When the Assyrian leadership began to fight among themselves and failed to maintain this strict policy throughout the far-flung districts, their empire was doomed, and they were supplanted after 605 by the Neo-Babylonians (also called the Chaldeans) under the leadership of Nebuchadnezzar.

It is possible, however, that the model of empire established and maintained for two hundred years by the Assyrians served as the impetus for another imperial power: the Persians from east of the Tigris. After pushing aside Nebuchadnezzar’s weak successors, King Cyrus captured Babylon in 539. The Persians addressed the problems created by Assyrian and Babylonian administrative policies and chose to accommodate their style of empire to the realities of distance and time. They invented a “pony express” system that allowed communication to flow over an area of two thousand miles in five days. The Persians also recognized that terror is effective only when constantly in use. As a result, they chose a more benevolent and bureaucratically based form of administration, allowing freedom of religion and appointing local leaders as Persian representatives whenever possible (Neh. 2:1–8). Only the rapacious ambitions of Alexander of Macedon and the decadence of its rulers could end the Persian Empire (ca. 325).

Egypt

While the Egyptians were able to create an advanced civilization at least as early as that in ancient Sumer (ca. 3500), it was very different in character. The differences arise from the more isolated nature of Egypt in relation to the rest of the Near East. To the east, the Red Sea and the wastelands of the Sinai Peninsula provide an effective barrier to invaders. Once the pharaohs established a line of fortresses to bar the narrow strip of land that connects Egypt and the Sinai, they were able to almost completely control the entrance of armies, migrant peoples, and caravanners. Only the Hyksos invaders (1750–1550) were able to establish themselves as foreign rulers over Egypt, and they too were eventually supplanted by a native Egyptian dynasty. The Libyan and Saharan deserts protected the western border. Although more open to invasion from Nubia in the south (especially after 900), Egypt, for much of its history, was protected by the cataracts, which limited navigation of the southern reaches of the Nile River.

Nearly all of Egypt’s culture and history has developed in and been sustained by the predictable inundations of the Nile River valley. The Nile flows north amid arid wastes and rocky desert outcrops, where farmers had to rely entirely on the river for irrigating their fields. As it enters the Mediterranean, the Nile spreads over the land into a fan-shaped delta and is dominated by papyrus marshes. It is customary to refer to the two regions of Egypt as Upper and Lower Egypt. But because the Nile flows from south to north, Upper Egypt is the southern area, from Thebes to Memphis, and Lower Egypt comprises the northern region, including the delta and eastern desert along the Mediterranean coast.

The natural flow of the Nile is interrupted south of Thebes by a series of rocky cataracts that makes river traffic nearly impossible. As a result, caravans bringing goods from Arabia, Nubia, and other African kingdoms were forced to disembark and march alongside the Nile rather than travel upon the river. This gave the Egyptians the opportunity to control the influx of people and products and, of course, to tax them. Although smuggling almost certainly occurred, it would have been much more difficult than along the more open borders of Mesopotamia.

Unlike the Tigris-Euphrates system, which could flood without warning or shift its channel, the Nile was a fairly consistent waterway. Its annual flood cycle was measured early in Egyptian history, and as a result the people and their rulers were able to plan their agricultural and economic activities with greater certainty than was possible in Mesopotamia. The constancy of life from year to year contributed to a culture that built for the ages and assumed a continuity of existence beyond this life into the next. Just as the Nilotic floods brought new layers of rich topsoil to fertilize and reinvigorate the fields each year, the ma’at (“peace”) of Egypt was believed to come from the goodwill of the gods and their god-king, the pharaoh.

The Egyptian climate is hot and arid. Daytime temperatures range into the upper 90s F nearly year-round, and this is magnified by the cloudless, sunny skies. It is no wonder, therefore, that the sun god Amon is one of the most powerful of the Egyptian deities. The extreme temperatures moderate somewhat in the evenings, with cooling breezes coming off the Nile and from the desert. In fact, in the desert it can be quite cold at night. Throughout the region, architectural and clothing styles are based on accommodation to the extreme ranges in temperature.

The small annual rainfall meant that the people were forced to rely on the Nile and on wells for their water. As a result, waterwheels and other forms of irrigation technology were developed to move the water into channels that could flood the field. The river also served as a travel link facilitating the transport of goods, building materials, and armies. Familiarity with travel on the Nile and its various characteristics also became a common feature in their literature:

Metaphors involving the marshes, where birds roost and crocodiles and hippopotami are hunted, appear in genres as diverse as love poetry and the teachings of sages.

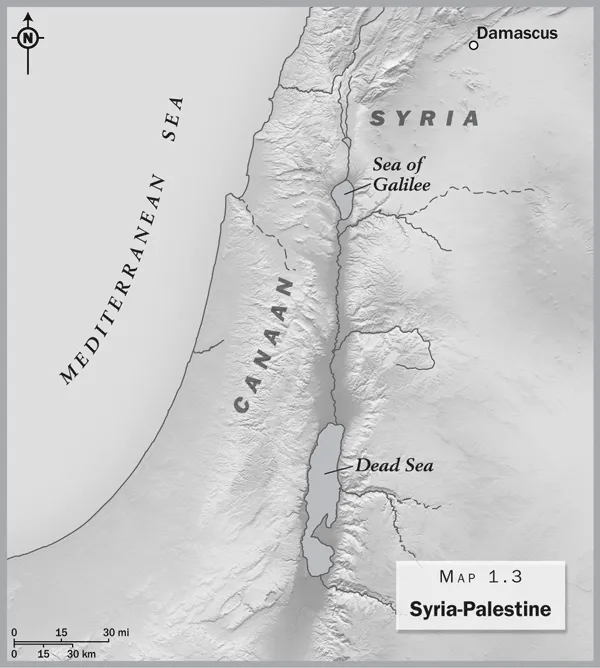

Syria-Palestine

Even though Syria-Palestine is the smallest of the Near Eastern regions, it is characterized by a much wider variety of topographic features, climatic zones, and population centers than either Egypt or Mesopotamia.

Syria

The northern range of this area includes Syria, the other Aramean states, and Phoenicia (modern Lebanon). From 1500 to 1200, the Hittite Empire dominated much of this northern area, stretching its hegemony beyond the boundaries of Anatolia (modern Turkey) and even challenging the Egyptians for control over Canaan. A significant economic power during this period was the port city of Ugarit, which controlled the carrying trade in the eastern Mediterranean. Ugarit is also responsible for the development of an alphabetic cuneiform writing system that would dramatically increase literacy and promote cultural identity within the smaller nations throughout the Near East. Its epic literature has many parallels in the Psalms and prophetic books:

In fact, the images of Yahweh as the master of the storm, the “Cloud Rider” (Ps. 68:4; Isa. 19:1), and the transcendent creator God (Isa. 40:28) were probably borrowed from or influenced by Ugaritic or Canaanite literature and their depictions of the gods El and Baal.

After 1200 a major political and cultural break occurred in the Near East when a mixed invasion force collectively known as the Sea Peoples challenged the power of the major cultures along the Mediterranean coastline. When the dust settled, the seaport city of Ugarit, which had dominated the Mediterranean carrying trade, had been destroyed and was never rebuilt. In subsequent centuries, the Phoenician seaports of Tyre and Sidon followed Ugarit as masters of Mediterranean ...