1

The Roman Near East

LINCOLN BLUMELL, JENN CIANCA, PETER RICHARDSON, AND WILLIAM TABBERNEE

Introduction

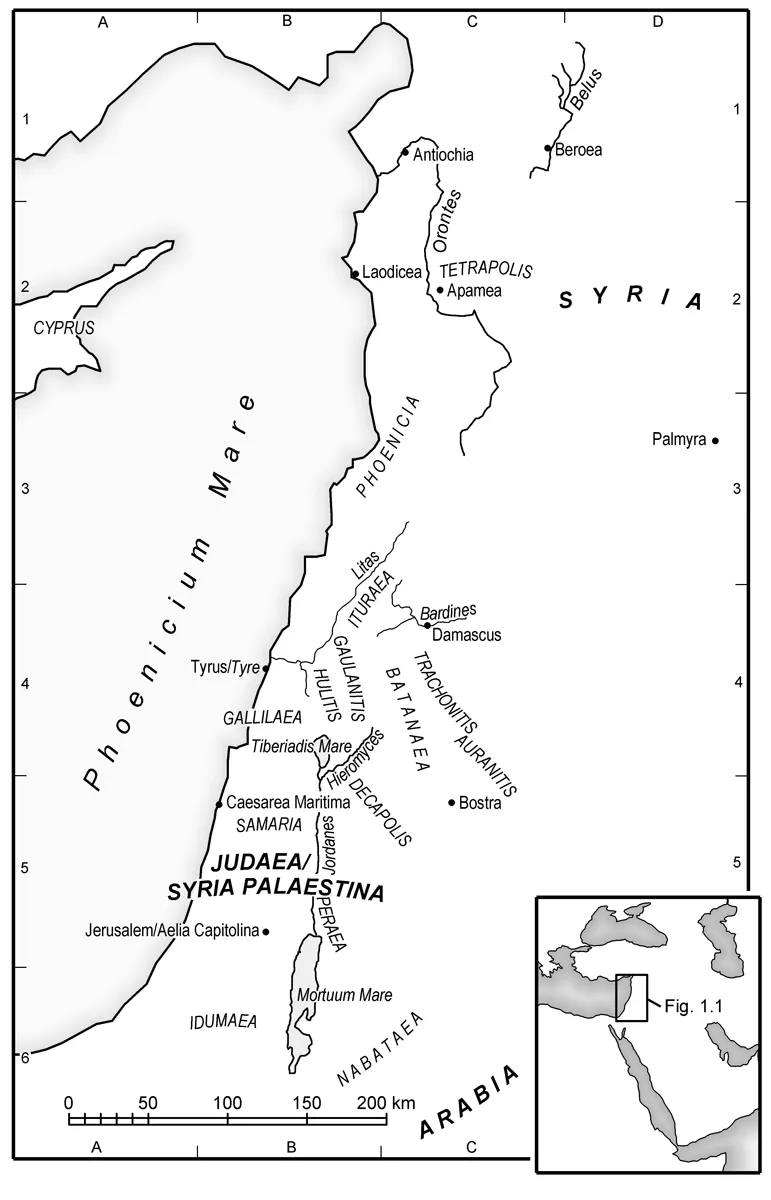

Rome first intruded into the Near East in 64–63 BCE during conquests by Pompey the Great (106–49 BCE). Initially, only Syria (including Phoenicia) was governed through Rome’s provincial system. Twenty years later the senate chose Herod the Great (r. 37–4 BCE) to rule Judaea, Samaria, and Galilee as a client kingdom (Richardson 1996), while Nabataea and Arabia were left alone. The earliest Christian communities developed in Jerusalem, Judaea, and Samaria (Acts 1:8) in the first century CE, and believers were soon found in Caesarea, Tyre, and Antioch. Christianity entered a difficult period with the Jewish Revolts of 66–74 and 132–135 CE. Though there was no formal parting of the ways (Richardson 2006)—Judaism and Christianity maintained a symbiotic relationship theologically, liturgically, architecturally, and ethically—the tensions led to Christianity developing independently and, ultimately, separating (S. Wilson 1995).

The Near East within the Roman Empire

Pompey’s organizational solution did not last, partly because the region was ethnically complex and historically convoluted. Syria in the north and Judaea in the south included various subregions, while semiautonomous cities survived from earlier Hellenistic foundations: along the Mediterranean coastline were cities such as Gaza, Dor, Tyre, Sidon, and, while inland, a Decapolis (ten cities) included centers such as Pella, Gadara, Hippos, and Gerasa.

Herod’s death in 4 BCE brought change. Galilee and Peraea went to Herod Antipas (r. 4 BCE–39 CE), while Hulitis, Gaulanitis, Batanaea, Auranitis, and Trachonitis were ruled by Herod Philip II (r. 4 BCE–33 CE). Judaea (including Samaria and Idumaea) was given to Herod Archelaus (r. 4 BCE–6 CE), but it was made a minor Roman province in 6 CE after he was deposed. Judaea was reunited and nominally autonomous between 41 and 44 CE, under Herod Agrippa I (r. 39–44 CE). It was briefly under direct Roman control, but Herod Philip’s territories passed to Agrippa’s son Marcus Julius Agrippa II in 48, with an imperial procurator responsible for taxes and peace. Following the Jewish Revolt of 66–74, Judaea was expanded to include most of Herod’s old territories; when Agrippa II died (ca. 90–100), Rome assumed direct control.

In 106 Trajan (r. 98–117) absorbed Nabataea and created the province of Arabia, whose capital was Bostra. Some Decapolis cities were transferred to the new province (Millar 1993, 95), some to Judaea, and some to Syria. Hadrian’s plan to make Jerusalem the new Roman colonia Aelia Capitolina, among other factors, triggered the Bar Kokhba Revolt of 132–135; in the aftermath Hadrian (r. 117–138) changed the province’s name to Syria Palaestina. Under Diocletian (r. 284–305) the region was divided into Palaestina Prima (Judaea, Samaria, Idumaea, Peraea, coastal plain) with Caesarea as administrative center, Palaestina Secunda (Galilee, Gaulanitis, the old Decapolis areas) with Scythopolis (Beth Shean) as capital, and Palaestina Tertia (the Negev, Nabataea) with Petra as center.

Syria’s divisions were similarly complex. Pompey had united Phoenicia, historically a collection of independent cities with extensive maritime trading contacts, with Syria; soon the “official use of the Phoenician language” died out (Millar 1993, 286). Syria Coele (Hollow Syria), an ambiguous geographical designation, once referred to the Decapolis region (Millar 1993, 423) but came to be used of the areas around and between the Lebanon and Anti-Lebanon Mountains (Strabo, Geogr. 16.2.1–2, 16, 21). Confusing matters, Septimius Severus (r. 193–211), when he split Syria, named the southern portion Syria Phoenice, though it included more than ancient Phoenicia, and the northern portion Syria Coele, though that term once applied to areas in southern Syria. Theodosius I (r. 379–395) divided Syria in four: Syria Coele became Syria Salutaris and Syria Euphratensis; Syria Phoenice became Phoenice and Phoenica Libanensis.

Fig. 1.1. Map of the Roman Near East [Richard Engle]

Geography and Ecology

Three tectonic plates—Africa, the Arabian plateau, and Asia Minor—collide within the Levant, generating earthquakes and volcanoes, rifts and uplifted mountains. Because it is an important hinge, there have always been substantial movements of humans, wildlife, and armies in the region. The mountains and rifts of the Levant run mainly north and south, but there are complicating transverse features, such as the hills of Upper Galilee and the Carmel range. Four rivers arise between the Lebanon and Anti-Lebanon ranges: the Orontes runs north and the Litani runs south from the Bekaa Valley before they both turn west to the Mediterranean; the Barada runs east from the Anti-Lebanons, evaporating in the desert; and the Jordan runs south from Mount Hermon (2814 m), creating the Sea of Galilee (ca. 200 m below sea level) and the Dead Sea (ca. 400 m below sea level). The paucity of permanent rivers ensures that springs and oases acquire extra importance. The climate is generally hotter and drier to the south and east, though there are dramatic variations. Soil has formed from decomposed geological formations, mostly limestone; even where soil nurtures shrubs and trees, settlement pressures and military actions (especially by Romans and Crusaders) have denuded the hills of vegetation, resulting in serious erosion. The land’s suitability for settlement, herding, and agriculture is varied, though the valley bottoms are usually fertile.

The Euphrates River, which marks the eastern limit of the Roman Near East, forms, along with the Tigris River, a “fertile crescent” that includes northern Syria and the coastal areas. This Fertile Crescent has indelibly stamped the region as a cradle of human civilization. The crescent’s interior is largely desert, while the Sinai Peninsula is a wilderness appendage. Trachonitis, Auranitis, and Gaulanitis include extensive volcanic areas.

Peoples and Religions

Settlements follow water, whether rivers and lakes (Apamea, Tiberias), oases (Palmyra, Jericho), permanent springs (Jerusalem, Petra), or aqueducts from mountain springs (Caesarea Maritima, Laodicea). Easily cultivated areas were settled early, less hospitable areas had small farmsteads, while desert areas supported nomadic or seminomadic groups who herded sheep and goats (Strabo, Geogr. 16.2.11), though the contrast between “the desert and the sown” (the title of Gertrude Bell’s 1907 book) is less sharp than sometimes thought. In the first century the Near East was a hodgepodge of local peoples interspersed with Greeks and Romans. In his Geographica Strabo mentions groups on the margins, such as Scenitae (“peaceful” [16.1.27]); Ituraeans and Arabians (“all of whom are robbers” [16.2.18]); Idumaeans (“shared in the same customs” with Jews [16.2.34]); “tent-dwellers and camel-herds” (16.4.2); Sabaeans (“beautifully adorned with temples and royal palaces” [16.4.2–3]); Ichthyophagi (“fisheaters” [16.4.4]); Spermophagi (“seedeaters” [16.4.9]); and Creophagi (“flesheaters” [16.4.9]).

PHOENICIANS

A sense of ethnicity and religion continued for some time in Phoenician city-states, including Tyre, Sidon, and Byblos. Their influence depended on commerce (notably purple dye) and exploration, together with their coinage (especially the Tyrian shekel) that was widely used until the second century CE. Phoenician deities were assimilated to Greco-Roman gods: Melqart, for example, was equated with Rome’s Heracles and Greece’s Hercules. Phoenicia practiced a northwest Semitic religion, adopting customs such as sacrifice (whether this included human sacrifice is still debated), offerings, prayer, purity concerns, and festivals (Schmitz 1992, 359–62). Berytus (Beirut) was not a Phoenician city, having been founded as a Roman colonia in 15 BCE.

ITURAEANS

Appearing desultorily in the historical record (Strabo, Josephus, New Testament, coins, inscriptions), Ituraea centered on Mount Hermon and extended into the Bekaa Valley, Trachonitis, Gaulanitis, Hulitis, and Upper Galilee. Widely dispersed inscriptions name Ituraeans as a Roman auxiliary unit noteworthy for archery; this auxiliary role continued after the ethnic group itself had virtually disappeared (E. Myers 2010). Nothing is known of their origins and very little about their religious activities, though they had cult centers on Mount Hermon (Dar 1993). Josephus (Ant. 13.11.3) claims that they were forcibly converted to Judaism by the Hasmonean Aristobulus I (r. 104–103 BCE), but he may exaggerate (Kasher 1988).

PALMYRENES

A distinctive culture emerged at Palmyra’s desert oasis by the first century BCE, with worship focused on Semitic deities, such as Baal Shamim and Bel. Family or clan burials were often in tower tombs, incorporating distinctive grave sculptures. Its architecture blended Roman and indigenous traditions: the Temple of Bel, for example, had a Palmyrene naos (inner sanctuary) within a Roman temenos (sacred enclosure) that included an altar, banqueting hall, and a ritual pool (Richardson 2002, 25–51). Palmyra prospered from the late first century BCE through the third century CE, reaping tariff income through trading via the Euphrates, the Silk Road, and transdesert routes. After revolting against Rome under Queen Zenobia (r. 270–272), Palmyra only partially recovered.

NABATAEANS

By the second century BCE, Nabataeans had displaced Edomites (Idumaeans) from east of the Dead Sea to west of it. By the next century, Nabataeans formed a prosperous kingdom stretching from southern Syria to the Mediterranean and the Red Sea (Strabo, Geogr. 15.4.21–26), which often conflicted with Jews. They were famous for sophisticated management of limited water resources and a magisterial skill in contructing rock-cut buildings whose details were indebted to Hellenistic architecture (Markoe 2003). Nabataean religion focused on Semitic divinities such as Dushara, al-Illat, and Atargatis. As wealthy middlemen in international trade between the Mediterranean and the East, the Nabataeans joined Rome in a military expedition to Arabia Felix under Aelius Gallus in 25–24 BCE, but they lost their separate identity when Rome created the province of Arabia.

Fig. 1.2. Temple of Bel, Palmyra [Peter Richardson]

SAMARITANS

When the northern kingdom of Israel was destroyed in 722 BCE, the continuing peoples were known as Samaritans. Following its revolt against Alexander the Great (r. 336–323 BCE), Samaria was again destroyed, and the main city (also called Samaria) was moved nearer Mount Gerizim. Augustus (r. 31 BCE–14 CE) made Samaria part of Herod’s kingdom. Herod built there extensively, including an imperial cult center at Samaria, which, in honor of Augustus, he renamed Sebaste (Sebastiya). Under Hadrian, a temple to Zeus Hypsistos (Highest) was built on the slopes of Mount Gerizim. Samaritanism, like Judaism, included animal sacrifice, ritual purity, and Torah (the five books of Moses). Samaritan synagogues were spread widely, in places such as Delos, Thessalonica, and Caesarea.

JEWS

During the Persian period, following the Babylonian exile of 587 BCE, Jews were loyal to Persia but restive under the Seleucids, until the Hasmonean Revolt (167–164 BCE) freed them from Syrian control. Dynastic conflicts led to Roman domination (63 BCE) and ultimately to an offer of the kingship to Herod. Though Herod was ethnically half Nabataean and half Idumaean, his grandfather had converted to Judaism (Richardson 1996). Herod rebuilt and extended the temple in Jerusalem, on which Jewish religion focused. Jews were found everywhere in the Roman Empire (possibly 10–15 percent of its population), worshiping in local synagogues (Richardson 2004, 111–85). Three revolts between 66 and 135 CE strained relations with Rome.

Trade, Commerce, and Roads

As Rome pursued extensive trade networks following Augustus’s Pax Romana (Roman peace), the Levant became an important transportation hub. Trade followed traditional routes across the Syrian and Arabian deserts and up from the Red Sea,...