This is a test

- 414 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Provides a model for examining the beliefs folk religions around the world and suggests biblical principles missionaries can use to deal with them.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Understanding Folk Religion by Hiebert, Paul G., Shaw, R. Daniel, Tienou, Tite in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Christian Ministry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Theology & ReligionSubtopic

Christian MinistrySECTION TWO

FOLK RELIGIOUS BELIEFS

All religions are rooted in deep beliefs about the nature of reality. This is also true of folk religions. When Western scholars and missionaries first encountered traditional religions around the world, they branded these as illogical superstitions because they did not pass the tests of formal Western logic. They assumed that people would leave their old beliefs when they saw the superiority of reason. Secular scholars went further. They saw Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism, and other formal religions as proto-logical because they did not meet the empirical tests of science.

The chapters in this section examine the logical foundations of folk religions, and seek to show that they help people make sense of the existential crises of their everyday lives. These religions do so by answering the key existential questions all humans must face. Four of these are studied. The first is finding meaning in this life and explaining the devastation death leaves behind for those who remain alive. The second is defining the good life and accounting for the crises that are very much a part of human experience, including sickness, barrenness, drought, floods, earthquakes, and failures. The third is planning and controlling one’s life and overcoming the problem of the unknown. The fourth is longing for justice and morality, and accounting for the presence of evil and oppression as a daily experience. After seeking to understand the answers given by traditional religions, we suggest guidelines for biblically informed Christian responses to these questions.

SECTION OUTLINE

Section Two examines folk religious beliefs, particularly as these relate to four central questions people seek to answer, and offers Christian responses to these questions. The approach is phenomenological—to try to understand the world as the people see it without passing judgment on their beliefs.

Chapter 5: How do people find meaning in life on earth, and how do they explain death?

Chapter 6: How do people try to get a good life, and how do they deal with misfortune?

Chapter 7: How do people seek to discern the unknown in order to plan their lives?

Chapter 8: How do people maintain a moral order, and how do they deal with disorder and sin?

5

THE MEANING OF LIFE AND DEATH

Is there meaning in human lives, or are people animals who die meaningless deaths? If there is no meaning, there is no need for them to give themselves to others or to live moral lives. Clifford Geertz points out that the search for meaning is a fundamental human craving, and that meaninglessness is worse than death (Geertz 1979). Many people have gone willingly to their deaths for the sake of their beliefs.

In formal religions, meaning is given by answering questions of ultimate reality—what are the cosmic origins, nature, purpose, and end of the universe, humankind, and the individual? Folk religions give people a sense of meaning by answering the existential questions of everyday life, and by providing the living a sense of place and worth in their society and world.

THE MEANING OF LIFE

All humans seek to make sense out of their lives. Two types of explanation are widely given: synchronic ones that help explain who humans are—the nature and structure of their being; and diachronic ones that tell where people came from and where they are going—the stories of their lives. Taken together these provide a bifocal view that helps people make sense of their lives as they live in a wide array of cultural contexts and belief systems around the world. Both synchronic and diachronic approaches need to be examined to see how folk religions give meaning to humans in their everyday lives.

SYNCHRONIC MEANINGS

Synchronic explanations give people a sense of meaning by showing them that their lives are structured and orderly. Disorder and chaos are commonly associated with meaninglessness, for if there is no order, things have no explanation. Synchronic meaning is given to life in five ways: (1) showing people who they are, (2) charting the progression of their lives, (3) assigning them a community to which they belong, (4) providing them a home in the world, and (5) giving worth to what they do and have.

MEANING IN BEING

Who am I? Most folk religions answer this question, in part, by giving people a sense of their theological identity—a definition of what it means ultimately to be human. This identity assigns them great worth, and sets them apart from animals and other earthly creatures. For example, each Alaskan tribe identifies itself as “the Human Beings.“ Tlingit means “the people.“ Yup’ik and Sugpiaq mean even more: “the real People.“ Regarding their beliefs, Michael Oleksa writes,

When the world was made, or more importantly, when the first human beings appeared, they were given their own way to live appropriately, in harmony with the forces, spirits, and creatures with whom they share the cosmos. The beginning of each child’s education is marked by this sense of self and collective identity. We are the human beings. We are the real people. Our ways are the ways human beings were from all eternity meant to follow. Any deviation—due to forgetfulness or carelessness—threatens to bring imbalance, and therefore catastrophe to the universe. To forget is to perish (1987, 8).

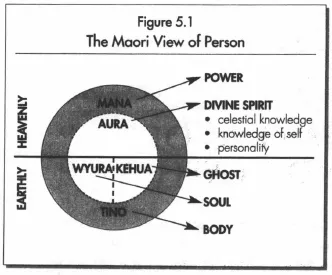

Folk theologies define humans, in part, by describing their component parts. Like many people around the world, the Maoris of New Zealand believe that people are made up of two components—a spirit that goes to the heavens at death, and a body that belongs to the material world. The Maoris divide these two parts into segments (Figure 5.1). The aura or divine spirit is self-aware and capable of celestial knowledge. It shapes a person’s personality, and survives in the other world after death. The aura is surrounded by mana, a shield of supernatural power that the person can create by rituals or acquire from people who have much of it. On earth a person also has a wyura or soul, and a tino or body. In death the wyura leaves the body and becomes a ghost or kehua, roaming the earth seeking food and shelter.

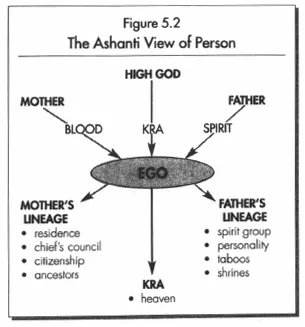

The Ashanti of Ghana believe that humans have three souls (Rattray 1923, 140ff.; Figure 5.2). From their mother they get their mogya, or blood and natural life. In earthly matters, therefore, they belong to their mothers’ matrilineage, which gives them their land, residence, citizenship, and earth-bound ancestors. They live with their matrilineal kin, and are ruled by its chief and his council. From their fathers they get their ntoro, or spiritual substance that gives them character, genius, temper, and personality. They belong to his spirit group, worship at his patrilineage shrines, and observe his spiritual taboos. From the high God each person receives an okra, or divine spirit, that is their conscience. Such theological understandings of humans give the Maori and Ashanti a sense of their special worth by showing them that they are more than animals.[1]

Scripture clearly establishes the identity of humans in their being—in the fact that they are created in the image of God. That image was tarnished by the fall in the Garden of Eden, and the whole of Scripture can be viewed as God’s re-creation of his image in human beings.

MEANING IN BECOMING

Meaning for individuals, in part, has to do with the progression of their lives. They start as infants—as nobodies, without titles or achievements. They become full humans—fathers and mothers, warriors, businesswomen, priests, presidents, and many other persons of importance. They end life as respected elders and honored saints.

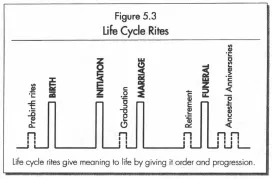

Most societies divide the progression of life into stages, and mark transitions by rituals. These “life cycle rites” transform persons from one level of identity to another, and, in so doing, give them a growing sense of worth and importance (Figure 5.3). The unborn become children, children become young adults, young adults marry and become parents, parents become elders, and elders become ancestors. The main rites celebrated in many societies around the world include birth, initiation, marriage, and funerals, but there are many others specific to different societies. For example, in the West baptisms, graduation ceremonies, and retirement parties mark transitions from one stage in life to another.

BIRTH RITES

Why are humans here? To be human requires an answer to this question. In the West, animals are simply born and plants grow from seeds. No explanations for their presence as individuals need be given because animals and plants do not have purposeful lives. To explain human births, on the other hand, is to turn newborn creatures into humans, and so to give meaning to them.

One question associated with birth the world over is “where do we come from?” The answers often given rise to ‘origin myths.’ The Samo of Papua New Guinea believe that an ancestral spirit enters a baby’s body at birth, thereby giving it life. The term kogooaiya, ‘to get an ancestral spirit,’ is used for births. The Aborigines of Australia believe that the spirits of the unborn live in holes in the earth. When a young woman carelessly walks over one of these, one of the spirits jumps into her body to be born. Moreover, the unborn spirits reside in particular geographic territories. By way of analogy, Americans might think of the spirits living in Minnesota as Minnesota spirits and those in Wisconsin as Wisconsin spirits. If a Minnesota woman is traveling in Wisconsin when she becomes pregnant, it is obvious that her child is a Wisconsinite. Consequently, the same family may have different territorial ‘spirits’ in it, somewhat in the way modern children obtain citizenship from the nation in which they are born, and one family may have children with different passports.

The Baoule of Côte d’Ivoire believe that there are three possible origins to babies. They may be strangers who come from the spirit world without any prior involvement in the family; they may be reincarnations of an ancestor (children are examined to see if they resemble any ancestor); and they may be gifts from God or from the genii of the forest due to the request of parents or the kindness of the spirits. Parents must determine at birth which type of child they have in order to treat it properly when it becomes sick.

A second question is when a person becomes human. Normally this occurs when the baby is given a name. A nameless child is not fully human—it is not a he or she but an “it.” To give it a name is to turn the baby into a member of the society. Many people wait to give a name until they are sure the life will remain. Among the Samo a child is not considered fully human until she or he has teeth and can walk and talk. This takes about three years, allowing family members time to determine which ancestor has returned to energize this life. Once determined, the child is given that ancestor’s name and joins the household as a functioning member (Shaw 1990, 81).

In most societies, names are not arbitrary labels. Frequently they are selected to reflect or create the personality of the child. Native Americans give names to their children that both reflect their budding personalities and are hoped to shape them—Eagle, Lovely, Warrior. Among the Eskimo, to call a person’s name is to call his or her spirit. Consequently, the living do not mention the dead by name for that will call back their spirit. The Akamba of Kenya name their children after the seasons, time of day, and other circumstances surrounding the birth. One father named his three sons after the morning, afternoon, and evening. Another named his son Mutisya—postponed—because his birth was delayed, and caused the father to be late for work.

A third question at birth has to do with paternity, for this often determines the child’s place in the community. There is seldom any question who the mother is, but the identity of the father is not always clear. This must be established socially for the child to have an identity in the community. In polyandrous societies the father must be chosen from among the husbands, and a ritual of paternity conducted. Among the Todas of South India, the first husband can claim the child by putting a small bow and arrow in a nearby tree. If he does not, the second husband can claim the child. This continues on down the line until a father is assigned. Among the Mukamba of East Africa, the mother is asked by the midwife, “Can I give this child to you to suckle?” If the mother answers yes, she declares that the child is the legitimate offspring of her husband. If she says no, the child is assumed to be illegitimate by either adultery or incest. Legitimate children are incorporated into the society with celebration, but the lot of illegitimate children is one of rejection and derision.

Another custom of paternal legitimation is called “couvad,” and is found among such widely scattered peoples as the Aino of northern Japan, the Caribs of South America, and in parts of China, India, and Spain. In this custom, the father goes to bed after the delivery of his child, and the mother returns to work. This not only helps the man to recover from the ordeal, but also enables him to lay claim to the child. In some cultures the rite is also performed to protect the vulnerable mother from evil spirits, who are tricked into attacking the husband in the delivery hut.

INITIATION RITES

All societies must determine when children become adults. Most have initiation rites to mark this transition. These rites are often associated with puberty and sexual maturity, but not necessarily so. What is important is that the young are now incorporated as full members in the society. The rites vary greatly according to gender. For example, the Samo rarely initiate males before they are in their late teens or early twenties, whereas females are often considerably younger.

One major function of initiation rites is to transform children into adults. Boys become men, girls become women, outsiders become members of the community, and strangers are brought into fellowship with the gods. Without initiation, they remained ‘boys’ and ‘girls’ all their lives.[2] For example, among the Marakwet of East Africa, women who are not initiated by circumcision are estranged outsiders. Only initiates have a right to contribute to and participate in community life, to own property, and to vote or be voted for. It is the old women who have suffered in past initiations who are often the firmest holders of traditional customs. Their attitude is often, “it will do her good, didn’t I go through it, why shouldn’t she, it will make a woman out of her.”

A second major function of initiation rituals is to educate initiates in the responsibilities of adult life. Young women are taught how to be good wives and mothers, men to be good husbands and fathers. There is instruction on how to relate to people of the opposite sex, and above all the need to be faithful to spouses. Throughout life, old men and women oversee the behav...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- SECTION ONE: DEVELOPING AN ANALYTICAL MODEL

- SECTION TWO: FOLK RELIGIOUS BELIEFS

- SECTION THREE: FOLK RELIGIOUS PRACTICES

- SECTION FOUR: CHRISTIAN RESPONSES TO FOLK RELIGION

- References

- Index

- About the Authors

- Notes

- Back Cover