![]()

1

Methodology

Into the Darko

If there’s no one beside you

When your soul embarks

Then I’ll follow you into the dark.

Death Cab for Cutie1

One of the more haunting songs (and captivating videos) of recent years is Death Cab for Cutie’s “I’ll Follow You into the Dark.” Lead singer Ben Gibbard looks at death, filtered through his painful Catholic parochial school experience. Even if heaven and hell are full, illuminated by “no vacancy” signs, he vows to accompany his love “into the dark.” It is a poignant and haunting pledge, an agnostic’s prayer. Gibbard believes there may be no blinding light or pearly gates awaiting us, but he and his love hold hands, “waiting for the hint of a spark.” Death Cab for Cutie express a hopeful doubt. They are willing to watch and wait, satisfied to find a flicker of eternity, a glimpse of the divine.

I invite readers to follow me into the dark of the movie theater. It may not produce a blinding light or usher viewers into a vision of pearly gates. But I hope it will provide a hint of a spark. A journey “into the dark” may seem like an odd invitation for a work in film and theology. Yet any light that theologians might lift up will arise at the end of the long and daunting tunnel through which we find ourselves crawling. Despite our unprecedented financial and scientific success in the modern era, the twenty-first century can be characterized as a return to the Dark Ages. We have discarded civil discourse in an effort to outshout each other. A new tribalism has resulted in civil wars and ethnic cleansings.2 Ancient battles between Christianity and Islam, the West and the East, have reared their ugly heads, and they show no signs of abating. The critiques of religion offered by Richard Dawkins and Sam Harris have become best sellers because of their insight, not merely their folly. We have offered far too much judgment, anger, and vitriol in the name of God. We must ask for forgiveness for our “unChristian” attitudes and actions.3 Any work of art, eager to offer hope, must be forged in the darkness of our current situation.

Teachers, ministers, and therapists who long to get involved in their postmodern constituents’ spiritual growth will find vexing shadows cast by our otherwise prosperous lives. The paradoxical reports of today’s adolescents as motivated but directionless, well-adjusted but wounded demonstrate the limits of unifying paradigms.4 Our autonomy has not necessarily resulted in the freedom we expected. To get to the heart of our matters, we must be willing to explore the hidden spaces of our psyche, to peer below the surfaces we’ve constructed on MySpace. Yet the movies offer such promises every single day. We follow conflicted characters through confusing situations. They emerge either weary and wiser or dead and defeated. The challenges confronting fictional characters become a vicarious opportunity for viewers to forge their character. We may discover our blind spots, recognize the limits of individualism, and acknowledge our need for community. What a sweet deal! We invest two hours in the dark (and ten dollars—or more) in exchange for moments of levity and clarity, a shift in perspective, signs of life.

This chapter is divided into four parts. It begins with a discussion of the transcendent possibilities of film and the difficulties in determining which movies matter. How can God communicate through such unlikely means as movies? The second section delves into the theological concept behind this phenomenon: general revelation. Efforts to explain the mysterious ways in which God speaks have led to much confusion. This section will examine the variety of terms and biblical evidence surrounding general revelation. The third part of this introduction explores my methodology, the messy merging of film and theology. This chapter concludes with an example of film and theology in action: a discussion of the cult film Donnie Darko (2001).

Film: Forming a Canon

So what constitutes a must-see movie? How do we measure a film’s impact across time? Filmmaker Paul Schrader wrestled with the concept of a cinematic canon in a lengthy 2006 article for Film Comment. In a brilliant essay incorporating the history of art, aesthetics, and criticism, Schrader describes the formation of a canon as a story: “To understand the canon is to understand its narrative. Art is a narrative. Life is a narrative. The universe is a narrative. To understand the universe is to understand its history. Each and every thing is part of a story— beginning, middle, and end.”5

As a Calvin College graduate raised within a deep theological tradition, Schrader also reconnected canonization to its religious roots. The establishment of a rule, an order, allowed early Christians to move from competing claims to a more unified people. The canonization process gave a nascent movement base, language, and common ground on which to build. The Nicene Creed, established in AD 325, has served as a baseline for orthodox Christian faith across the centuries. It tells a potent story in a compact form.

Yet the 1945 discovery of the Gospels of Thomas and Philip at Nag Hammadi, Egypt, reopened questions of canonization. Why were the Gnostic Gospels excluded from the canon of Scripture? And why were the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John set apart as authoritative? Ancient debates about orthodoxy have turned into a surprisingly commercial industry, from the best-selling books of Elaine Pagels to the controversies surrounding Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code.6 Pagels connected the Gnostic Gospels to the historic suppression of female voices within church and society. Dan Brown highlighted the people and politics inherent in the process, turning ancient debates into page-turning drama. The process of elevating certain texts over others played into our contemporary fascination with conspiracy theories. Church authority has come into question. Issues that Christians thought were settled centuries ago have resurfaced, forcing everyone to examine the roots of orthodox Christian faith. Scholarly work regarding the canonization process and early church history has proven remarkably timely.7

The founders of “cinematic faith” have also been struggling to retain their authority. Paul Schrader has devoted his life to exploring the transcendent possibilities of cinema. His legacy as critic, screenwriter, and director is secured.8 Yet he approached the subject of a cinematic canon with a sense of ennui, lamenting the decline of film criticism and the film industry. Schrader recognized that “motion pictures were the dominant art for the 20th century.” But he saw his work as riding “the broken-down horse called movies into the cinematic sunset.” For Schrader, the formation of a cinematic canon suggests that movies have run their course. His list of the sixty essential films reflected his bias against recent movies, naming just four films created since 1990.9 Are movies bound for the museum destined to be embalmed? Boston University film professor Ray Carney worries that a digitized, sensationalized cinema has replaced the artful films of Ingmar Bergman, Michelangelo Antonioni, Federico Fellini, and Jean-Luc Godard. Carney feels that “the ‘spiritual’ films have been shoved aside, . . . those that offer ‘a transformative experience,’ those that ‘expose us to new ways of being and feeling and knowing.’ ”10 Carney laments that even recent critically acclaimed films of Abbas Kiarostami (A Taste of Cherry, 1997) and Todd Haynes (Far from Heaven, 2002) have proven too difficult for contemporary audiences accustomed to easy gratification. Such critical doomsaying is a time-honored tradition, echoing back to Rudolph Arnheim's 1939 complaints about the death of silent cinema: "The talking film as a means of representation precludes artistic creation."11

Yet the passion demonstrated on the bulletin boards of the Internet Movie Database suggests that devoted film fandom has never been more vital. As a freshman at Pomona College, Kate Brokaw declared, “The more popular contemporary movies in my circle of friends are the movies that are more challenging; the ones that are doing something offbeat or different in a narrative or visual sense—like anything by David Finch or Wes Anderson, or Richard Linklater’s Waking Life.”12 The emerging canon is just as spiritual as its forerunners but in different ways. Bigger, louder, and faster films can be empty and illusory, but a rigorous cutting pace has not ruined the transcendent possibilities of cinema. Shorter attention spans need not squelch the Spirit. Rather, the increased availability of moving images has resulted in an even greater hunger for enlightenment within entertainment. Given the nascent possibilities found in digital technology and Internet distribution, I do not share the skepticism of Schrader and Carney. Movies as a theatrical event may be waning. But moving images are just starting to animate us in significant and spiritual ways. This volume will explore the emerging cinematic canon, wading into the dark with enthusiasm rather than lament.

A few institutions have polled scholars, critics, and stars in an effort to construct a definitive list. The British Film Institute’s Sight & Sound magazine has taken the critical pulse of cinematic history each decade since 1952. Citizen Kane has topped the international film critics’ list since the 1962 poll (with The Godfather and Vertigo slowly gaining on it).13 Yet if you ask younger moviegoers about Citizen Kane, it will likely inspire modest enthusiasm. In 1996, to celebrate the centennial of cinema, the American Film Institute polled critics and filmmakers to create a list of "The 100 Greatest American Movies of All Time."14 Once again, Citizen Kane topped the charts with The Godfather a close second. But how definitive or untainted is such a proposed canon, especially when the American Film Institute turned its lists into a series of television specials, raising money for its institution? Critic Jonathan Rosenbaum rightly took the AFI to task for its isolationism.15 What of world cinema? Rosenbaum acknowledged the power and importance of a film canon as an educational tool. It should start arguments about the art of cinema, causing us to reflect on what matters and why. But Rosenbaum proposed his own alternate Top 100 (and eventually an essential, idiosyncratic Top 1000).16

Whose list should we pay attention to? Where are the most credible sources? Scholars attempt to measure a film’s impact in a variety of ways. Honors and prizes like the Academy Awards or the Cannes Film Festival Golden Palm confer a certain status (although politics often influence the outcome). Weaker films can win in a year of lesser competition (like The Greatest Show on Earth’s Academy Award for Best Picture in 1952). Box office receipts can determine popularity but often indicate more about marketing rather than enduring influence. Movie reviews can also provide a snapshot of initial reactions to a film. What used to take hours of combing through libraries in search of critical reactions is gathered on Web sites like www.metacritic.com or www.rottentomatoes.com. Critical consensus is just a mouse click away.

Yet critics and audiences can often overlook a film that comments too closely on its current context. Frank Capra’s It’s a Wonderful Life was neglected on its initial 1946 release, failing to recoup a $500,000 budget.17 Post–World War II audiences looking for escape found George Bailey’s “what if ” trip to Potterville too dark a vision. Despite five Academy Award nominations, it walked away without a prize. Only after the studio failed to renew the copyright for It’s a Wonderful Life did it become the beloved Christmas classic through repeated television screenings. The Shawshank Redemption was also greeted with indifference in its 1994 theatrical release. With a domestic gross of only $28 million, it barely recouped its modest budget. Despite seven Oscar nominations, Shawshank never even reached one thousand theaters. Did assumptions about dark, prison dramas keep viewers away? Shawshank’s redemption took place everywhere but the big screen—in home video (it was the biggest rental of 1995), on DVD (through multiple releases), and on nonpremium cable television. Since its network television debut in June 1997, The Shawshank Redemption has run on TNT an average of six times per year—more than fifty times overall.18 Obviously, home viewers join Andy and Red on their hard-earned trip out of Shawshank again and again. Readers of England's Empire Magazine recently ranked Shawshank as their favorite film of all time.19

Some cinematic treasures are often not discovered until after they’ve left theaters. It takes time to appreciate the depth of some filmmakers’ vision. Today’s bombs may become tomorrow’s classics. Will appreciation for M. Night Shyamalan’s The Village (2004) and Lady in the Water (2006) grow the further we get from September 11, 2001? Or were audiences and critics right to deride these postmodern fairy tales forged in our fearful times? The combustible mix of oil and religion in There Will Be Blood (2007) may have arrived too close to our war in Iraq to appreciate its prescience. The transcendent hope provided by Into the Wild (2007) may grow in appreciation the more we preserve our tenuous environment. As the sheer volume of entertainment grows, the process of separating cinematic gold from forgettable dross will prove increasingly important.

With so many variables to measure a movie’s worth, how might a discerning filmgoer determine which films to watch? What about a poll of nonexperts comprised of average moviegoers who know what they like and who celebrate movies that moved them, even if they do not have the critical grids or categories to articulate why? Since film is among our most public arts—a truly mass medium—we need an audience-driven, receptor-oriented methodology. What films evoke ongoing passion and repeat viewings? Could we combine both the critical admiration for craft (in Citizen Kane) with the visceral thrill of entertainment (in Star Wars)? Where do art, commerce, and enduring impact coalesce?

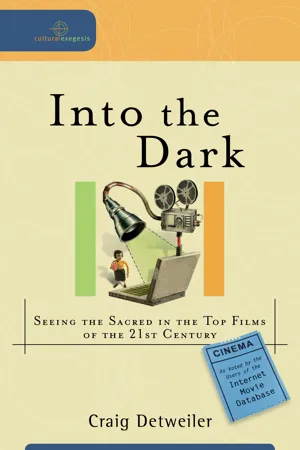

The IMDb and the New Canon

To determine which movies inspired film fans across the world, I turn to the Internet Movie Database (www.imdb.com). As an online encyclopedia created and updated by moviegoers, the IMDb is a remarkable tool to determine the new cinematic canon. It is a receptor-oriented database, culling from the collective wisdom of the global film-watching community. It is driven by love and devotion and fueled by passionate opinions. Some may consider IMDb users a little obsessive. It may attract people who have too much time on their hands, who care more about movies than everyday life. How representative are people who invest too much time online? Yet I admire the unguarded responses that IMDb users offer up so freely and frequently. Nobody is paid for their reviews. Unlike the Oscars, the votes are not tainted by personal grudges or professional jealousy. While global in scope, all politics (and opinions) are local. As Amazon.com serves as the one-stop shop for book buying and reading capsule reviews, so the IMDb gathers information and posts reviews from both rabid and casual film fans. It is a dynamic, constantly evolving forum of opinions and insights. The IMDb offers both a long view of cinematic history and an immediate snapshot of a film’s relative popularity and power.

The IMDb publishes an evolving list of the Top 250 films of all time (see appendixes A and C). It invites millions of users to rate...