![]()

ECONOMICS

The Bitter Rind: Inflation

“Nothing so weakens government as persistent inflation.”

- John Kenneth Galbraith

Inflation is the bitter rind in the investment mix. Inflation can spoil the otherwise perfect labor of any investor and render an investment plan pointless. No doubt we all understand the basic concept: Inflation makes things go up in price.

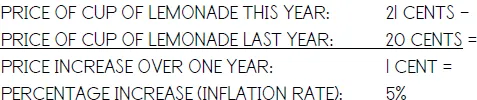

If there’s high inflation in the state of New Lemonade, a cup of lemonade will become less affordable every day. In other words, it will rise in price. While a cup of lemonade was selling for 20 cents last year, this year, it’s selling for 21 cents. The increase in price is one penny, an increase in percentage terms of 5%:

We can say that the inflation rate is 5%. The inflation rate is the rate at which prices increase over time. Historically, the average annual inflation rate runs around 3%, but there have been periods where inflation has been much higher.

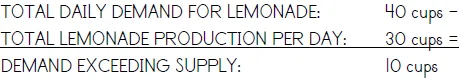

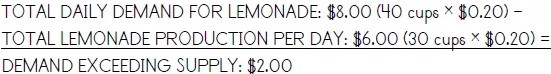

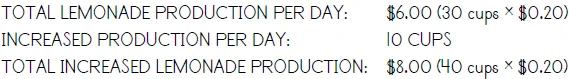

What causes this bizarre result? It doesn’t necessarily seem a foregone conclusion that prices should always go up, but they seem to. Economists endlessly debate the reasons. Most economists believe that inflation is caused by “too much money chasing too few goods.” In other words, if people have a lot of money to spend but not many things to spend it on, prices will rise. For example, if more and more people have more and more money in Lemonville, there will be a lot of money flowing around to buy lemonade. In fact, people may be throwing money at lemonade faster than Lucinda Lemonade Inc. and other stands can squeeze the stuff. If this occurs, the price of lemonade will rise. It’s a simple case of supply and demand. If the demand for lemonade increases while the supply does not, an imbalance will result and prices will rise. Let’s look at a specific example to make sure we really understand the concept. Suppose people in Lemonville demand 40 cups of lemonade each day, while all the lemonade stands put together in Lemonville are only able to squeeze out 30. Demand thus exceeds supply by 10 cups:

Since we know that a cup of lemonade costs 20 cents, we can also express this imbalance in terms of dollars:

There are two more dollars of demand for lemonade than there is supply. In other words, there’s an extra $2 sloshing around the pockets of Lemonville residents than there is lemonade to buy.

There are two ways for this imbalance to be corrected. Either the town’s lemonade stands will (1) raise their prices to soak up the excess money, or (2) they will improve their productivity to squeeze more cups.

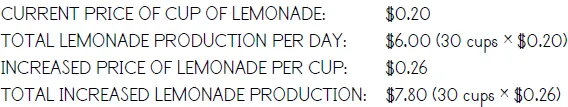

Let’s look at option #1: Lemonade stand owners being businesspeople, they will choose to raise their prices if they can. Whether they can or not is determined by whether they have what’s called pricing power — the ability to raise their prices without losing customers. If lemonade stands have pricing power, they can raise their prices to $0.26 per cup and take advantage of the excess demand:

By raising their prices to $0.26 a cup, the lemonade stands have brought the production of lemonade back in line with demand. They can’t really push their prices much higher because there’s only $8.00 per day in available daily dollar demand and they have already pushed production up to $7.80 per day. They are now soaking up the total money supply. In other words, they are charging nearly the highest prices that the market will bear.

Now let’s look at option #2: If the lemonade stands can buy new technology that will allow them to produce more lemonade, some smart, enterprising owner will eventually choose that option in order to undercut the competition. Let’s assume that Meg learns about new electric lemon squeezers that allow lemonade to be made much faster than the old-fashioned manual kind (which in turn makes lemonade faster than squeezing lemons by hand). Meg buys an electric squeezer and finds that she can now produce twice as many cups of lemonade each day than she used to. Where she used to be able to squeeze only 10 cups per day, now she can squeeze 20, adding 10 more cups to the total daily output in Lemonville. The town’s total output of lemonade is now 40, bringing the supply-demand situation back into balance:

By raising the total amount of lemonade produced each day to 40 cups, Meg has raised the total dollar output of lemonade production each day to $8.00, perfectly matching demand. Balance has been restored.

More impressively, Meg has stolen Lucinda’s pricing power. Now Lucinda can’t raise her prices because her customers will just go to Meg where they can buy more cups at the cheap price of 20 cents. Increasing productivity, that is increasing the daily output of lemonade, has led to an environment without pricing power. It has also led to an environment of economic growth because the dollar value of goods produced is increasing. This is the best economic environment to have: one where economic growth exists hand in hand with increased productivity so that excess demand does not lead to inflation.

As you can appreciate, this is a difficult balance to pull off. If there isn’t the means required to increase productivity (i.e., new electric juicers), then prices will rise without increased output of lemonade. The result will be good old 1970s-style stagflation: inflation on top of a period of declining growth — a recession.

This is why innovation is so crucial to a growing economy. A high growth/high productivity/low inflation environment is what creates jobs, wealth, and prosperity. The opposite leads to economic decline. Enough said.

Controlling the Flow: Interest Rates

“I don’t believe in princerple, but oh I du in interest.”

- James Russell Lowell

In the last chapter, we talked about how “too much money chasing too few goods” causes inflation. And we also showed how “too few goods” (too few cups of lemonade) can result from a lack of productivity. Well, what about the money side? In other words, how does “too much money” happen?

“Too much money” may not sound like a problem. If such a problem exists, you might like to be the one to have it. Too much money is only a problem if accompanied by “too few goods.” If increased productivity leads to enough lemonade for all that money to absorb, it’s fine. But if there’s more money than lemonade, the imbalance called inflation results.

Well, how does “too much money” occur? One way is by the government printing too much of it. It may have often occurred to you that if the government needs money, why don’t they just make more. The answer is that printing more dollars just pumps more money into the system. And too much money without a corresponding increase in production causes inflation. If the government were to just print money any time they felt the urge, it would lead to very bad inflation.

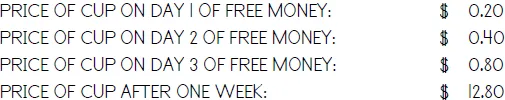

Money printed without corresponding growth is not a true increase in wealth because the money loses its value due to inflation. For example, let’s assume the citizens of Lemonville suddenly have much more money because the government is giving away dollar bills on street corners. The government passes a new law that says that money should be given out from corner stands, and that people can take as much as they want. If the stand runs out, the government prints more. Naturally, every Lemonville resident visits the stand and carts away as much money as possible. After awhile, every resident has a big fat wallet. Now when they go buy lemonade, they really don’t care what price they pay. After all, money is free and anyone can afford as much as they want. Sounds like lemonade ambrosia.

But watch what happens:

Meg and Lucinda both find that they can charge as much as they want because the market will bear an infinite price. They double their prices daily, finding that no matter how high they go, they can still go higher. Money is so free that it has lost its meaning. Prices of lemonade go through the roof:

You get the idea. Soon a cup of lemonade will cost over a thousand dollars. This is what’s called hyperinflation, inflation so extreme that money loses its value. People start hoarding lemonade because the price only goes up, up, up. Soon, the supply starts to run out, leading to even higher prices. Even Lemonville millionaires cannot afford a cup of lemonade. As fast as they can cart dollars away from the money stands, the price goes up past the point at which they can afford it. After some time, the money, or currency, has been debased, meaning it has been rendered valueless. At the point where no sum of money can buy you lemonade, money has lost its purpose. The economy has effectively ceased operating, and the results can be disastrous.

Some of the more harmful results of this scenario are at first difficult to predict. Meg and Lucinda, for example, would soon leave the lemonade business. After all, why should they work so hard squeezing lemons if money is free on street corners? And as fast as they raise their prices for lemonade, a chain reaction causes the supermarkets to raise the price of lemons, making business impossible. The cycle becomes an especially vicious one. At a certain point, the incentives to work, save, invest, and do all things productive disappear. Chaos and social disorder result.

This is why nations without good monetary policy (control of the money supply) often have failing economies. And failing economies lead to poverty. The bottom line is that it’s crucial that a government control the monetary supply. In other words, a country cannot simply print more money to solve its problems. A country that prevents an oversupply of money is a country with monetary discipline.

How then does a government control the amount of money flowing down Main Street? By regulating the cost of money, otherwise known as interest rates. It being impractical for any government to really turn on and off the printing presses, they use a better trick: controlling the cost of money by controlling interest rates. In the United States, this duty falls to the Federal Reserve (the Fed), the government entity responsible for monetary policy. The Fed meets regularly to decide on interest rates. When they feel there is too much money flowing through the system, they make money more expensive—that is, they raise interest rates. When they fell there is too little money, they make money cheaper—they lower interest rates. The Fed doesn’t actually change all interest rates. Instead, they change a key rate known as the federal funds target rate, whi...