![]()

EDGAR HUNTLY;

or,

MEMOIRS OF A SLEEP-WALKER

![]()

TO THE PUBLIC

THE flattering reception that has been given, by the public, to Arthur Mervyn, has prompted the writer to solicit a continuance of the same favour, and to offer to the world a new performance.

America has opened new views to the naturalist and politician, but has seldome furnished themes to the moral painter. That new springs of action, and new motives to curiosity should operate; that the field of investigation, opened to us by our own country, should differ essentially from those which exist in Europe, may be readily conceived. The sources of amusement to the fancy and instruction to the heart, that are peculiar to ourselves, are equally numerous and inexhaustible. It is the purpose of this work to profit by some of these sources; to exhibit a series of adventures, growing out of the condition of our country, and connected with one of the most common and most wonderful diseases or affections of the human frame.

One merit the writer may at least claim; that of calling forth the passions and engaging the sympathy of the reader, by means hitherto unemployed by preceding authors. Puerile superstition and exploded manners; Gothic castles and chimeras, are the materials usually employed for this end. The incidents of Indian hostility, and the perils of the western wilderness, are far more suitable; and, for a native of America to overlook these, would admit of no apology. These, therefore, are, in part, the ingredients of this tale, and these he has been ambitious of depicting in vivid and faithful colours. The success of his efforts must be estimated by the liberal and candid reader.

C.B.B.

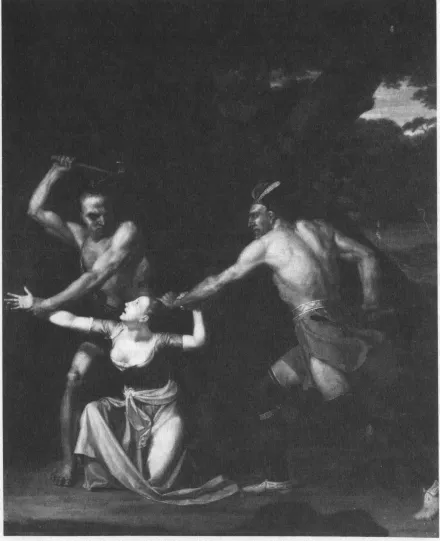

John VanderlynThe Death of Jane McCrea (ca. 1803)Courtesy of Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, Connecticut

![]()

EDGAR HUNTLY;

OR, MEMOIRS OF A SLEEP-WALKER.

CHAPTER I

I SIT down, my friend, to comply with thy request. At length does the impetuosity of my fears, the transports of my wonder permit me to recollect my promise and perform it. At length am I somewhat delivered from suspence and from tremors. At length the drama is brought to an imperfect close, and the series of events, that absorbed my faculties, that hurried away my attention, has terminated in repose.

Till now, to hold a steadfast pen was impossible; to disengage my senses from the scene that was passing or approaching; to forbear to grasp at futurity; to suffer so much thought to wander from the purpose which engrossed my fears and my hopes, could not be.

Yet am I sure that even now my perturbations are sufficiently stilled for an employment like this? That the incidents I am going to relate can be recalled and arranged without indistinctness and confusion? That emotions will not be re-awakened by my narrative, incompatible with order and coherence? Yet when I shall be better qualified for this task I know not. Time may take away these headlong energies, and give me back my ancient sobriety: but this change will only be effected by weakening my remembrance of these events. In proportion as I gain power over words, shall I lose dominion over sentiments. In proportion as my tale is deliberate and slow, the incidents and motives which it is designed to exhibit will be imperfectly revived and obscurely pourtrayed.

O! why art thou away at a time like this? Wert thou present, the office to which my pen is so inadequate would easily be executed by my tongue. Accents can scarcely be too rapid, or that which words should fail to convey, my looks and gestures would suffice to communicate. But I know thy coming is impossible. To leave this spot is equally beyond my power. To keep thee in ignorance of what has happened would justly offend thee. There is no method of informing thee except by letter, and this method, must I, therefore, adopt.

How short is the period that has elapsed since thou and I parted, and yet how full of tumult and dismay has been my soul during that period! What light has burst upon my ignorance of myself and of mankind! How sudden and enormous the transition from uncertainty to knowledge!—

But let me recall my thoughts: let me struggle for so much composure as will permit my pen to trace intelligible characters. Let me place in order the incidents that are to compose my tale. I need not call on thee to listen. The fate of Waldegrave was as fertile of torment to thee as to me. His bloody and mysterious catastrophe equally awakened thy grief, thy revenge, and thy curiosity. Thou wilt catch from my story every horror and every sympathy which it paints. Thou wilt shudder with my forboding and dissolve with my tears. As the sister of my friend, and as one who honours me with her affection, thou wilt share in all my tasks and all my dangers.

You need not be reminded with what reluctance I left you. To reach this place by evening was impossible, unless I had set out early in the morning, but your society was too precious not to be enjoyed to the last moment. It was indispensable to be here on Tuesday, but my duty required no more than that I should arrive by sun-rise on that day. To travel during the night, was productive of no formidable inconvenience. The air was likely to be frosty and sharp, but these would not incommode one who walked with speed. A nocturnal journey in districts so romantic and wild as these, through which lay my road, was more congenial to my temper than a noon-day ramble.

By night-fall I was within ten miles of my uncle’s house. As the darkness increased, and I advanced on my way, my sensations sunk into melancholy. The scene and the time reminded me of the friend whom I had lost. I recalled his features, and accents, and gestures, and mused with unutterable feelings on the circumstances of his death.

My recollections once more plunged me into anguish and perplexity. Once more I asked, who was his assassin? By what motives could he be impelled to a deed like this? Waldegrave was pure from all offence. His piety was rapturous. His benevolence was a stranger to remisness or torpor. All who came within the sphere of his influence experienced and acknowledged his benign activity. His friends were few, because his habits were timid and reserved, but the existence of an enemy was impossible.

I recalled the incidents of our last interview, my importunities that he should postpone his ill-omened journey till the morning, his inexplicable obstinacy; his resolution to set out on foot, during a dark and tempestuous night, and the horrible disaster that befel him.

The first intimation I received of this misfortune, the insanity of vengeance and grief into which I was hurried, my fruitless searches for the author of this guilt, my midnight wanderings and reveries beneath the shade of that fatal Elm, were revived and re-acted. I heard the discharge of the pistol, I witnessed the alarm of Inglefield, I heard his calls to his servants, and saw them issue forth, with lights and hasten to the spot whence the sound had seemed to proceed. I beheld my friend, stretched upon the earth, ghastly with a mortal wound, alone, with no traces of the slayer visible, no tokens by which his place of refuge might be sought, the motives of his enmity or his instruments of mischief might be detected.

I hung over the dying youth, whose insensibility forbade him to recognize his friend, or unfold the cause of his destruction. I accompanied his remains to the grave, I tended the sacred spot where he lay, I once more exercised my penetration and my zeal in pursuit of his assassin. Once more my meditations and exertions were doomed to be disappointed.

I need not remind thee of what is past. Time and reason seemed to have dissolved the spell which made me deaf to the dictates of duty and discretion. Remembrances had ceased to agonize, to urge me to headlong acts, and foster sanguinary purposes. The gloom was half dispersed and a radiance had succeeded sweeter than my former joys.

Now, by some unseen concurrence of reflections, my thoughts reverted into some degree of bitterness. Methought that to ascertain the hand who killed my friend, was not impossible, and to punish the crime was just. That to forbear inquiry or withold punishment was to violate my duty to my God and to mankind. The impulse was gradually awakened that bade me once more to seek the Elm; once more to explore the ground; to scrutinize its trunk. What could I expect to find? Had it not been an hundred times examined? Had I not extended my search to the neighbouring groves and precipices? Had I not pored upon the brooks, and pryed into the pits and hollows, that were adjacent to the scene of blood?

Lately I had viewed this conduct with shame and regret; but in the present state of my mind, it assumed the appearance of conformity with prudence, and I felt myself irresistably prompted to repeat my search. Some time had elapsed since my departure from this district. Time enough for momentous changes to occur. Expedients that formerly were useless, might now lead instantaneously to the end which I sought. The tree which had formerly been shunned by the criminal, might, in the absence of the avenger of blood, be incautiously approached. Thoughtless or fearless of my return, it was possible that he might, at this moment, be detected hovering near the scene of his offences.

Nothing can be pleaded in extenuation of this relapse into folly. My return, after an absence of some duration, into the scene of these transactions and sufferings, the time of night, the glimmering of the stars, the obscurity in which external objects were wrapped, and which, consequently, did not draw my attention from the images of fancy, may, in some degree, account for the revival of those sentiments and resolutions which immediately succeeded the death of Waldegrave, and which, during my visit to you, had been suspended.

You know the situation of the Elm, in the midst of a private road, on the verge of Norwalk, near the habitation of Inglefield, but three miles from my uncle’s house. It was now my intention to visit it. The road in which I was travelling, led a different way. It was requisite to leave it, therefore, and make a circuit through meadows and over steeps. My journey would, by these means, be considerably prolonged, but on that head I was indifferent, or rather, considering how far the night had already advanced, it was desirable not to reach home till the dawn.

I proceeded in this new direction with speed. Time, however, was allowed for my impetuosities to subside, and for sober thoughts to take place. Still I persisted in this path. To linger a few moments in this shade; to ponder on objects connected with events so momentous to my happiness, promised me a mournful satisfaction. I was familiar with the way, though trackless and intricate, and I climbed the steeps, crept through the brambles, leapt the rivulets and fences with undeviating aim, till at length I reached the craggy and obscure path, which led to Inglefield’s house.

In a short time, I descried through the dusk the widespread branches of the Elm. This tree, however faintly seen, cannot be mistaken for another. The remarkable bulk and shape of its trunk, its position in the midst of the way, its branches spreading into an ample circumference, made it conspicuous from afar. My pulse throbbed as I approached it.

My eyes were eagerly bent to discover the trunk and the area beneath the shade. These, as I approached, gradually became visible. The trunk was not the only thing which appeared in view. Somewhat else, which made itself distinguishable by its motions, was likewise noted. I faultered and stopt.

To a casual observer this appearance would have been unnoticed. To me, it could not but possess a powerful significance. All my surmises and suspicions, instantly returned. This apparition was human, it was connected with the fate of Waldegrave, it led to a disclosure of the author of that fate. What was I to do? To approach unwarily would alarm the person. Instant flight would set him beyond discovery and reach.

I walked softly to the road-side. The ground was covered with rocky masses, scattered among shrub-oaks and dwarf-cedars, emblems of its sterile and uncultivated state. Among these it was possible to elude observation and yet approach near enough to gain an accurate view of this being.

At this time, the atmosphere was somewhat illuminated by the moon, which, though it had already set, was yet so near the horizon, as to benefit me by its light. The shape of a man, tall and robust, was now distinguished. Repeated and closer scrutiny enabled me to perceive that he was employed in digging the earth. Something like flannel was wrapt round his waist and covered his lower limbs. The rest of his frame was naked. I did not recognize in him any one whom I knew.

A figure, robust and strange, and half naked, to be thus employed, at this hour and place, was calculated to rouse up my whole soul. His occupation was mysterious and obscure. Was it a grave that he was digging? Was his purpose to explore or to hide? Was it proper to watch him at a distance, unobserved and in silence, or to rush upon him and extort from him by violence or menaces, an explanation of the scene?

Before my resolution was formed, he ceased to dig. He cast aside his spade and sat down in the pit that he had dug. He seemed wrapt in meditation; but the pause was short, and succeeded by sobs, at first low, and at wide intervals, but presently louder and more vehement. Sorely charged was indeed that heart whence flowed these tokens of sorrow. Never did I witness a scene of such mighty anguish, such heart-bursting grief.

What should I think? I was suspended in astonishment. Every sentiment, at length, yielded to my sympathy. Every new accent of the mourner struck upon my heart with additional force, and tears found their way spontaneously to my eyes. I left the spot where I stood, and advanced within the verge of the shade. My caution had forsaken me, and instead of one whom it was duty to persecute, I beheld, in this man, nothing but an object of compassion.

My pace was checked by his suddenly ceasing to lament. He snatched the spade, and rising on his feet began to cover up the pit with the utmost diligence. He seemed aware of my presence, and desirous of hiding something from my inspection. I was prompted to advance nearer and hold his hand, but my uncertainty as to his character and views, the abruptness with which I had been ushered into this scene, made me still hesitate; but though I hesitated to advance, there was nothing to hinder me from calling.

What, ho! said I. Who is there? What are you doing?

He stopt, the spade fell from his hand, he looked up and bent forward his face towards the spot where I stood. An interview and explanation were now methought unavoidable. I mustered up my courage to confront and interrogate this being.

He continued for a minute in his gazing and listening attitude. Where I stood I could not fail of being seen, and yet he acted as if he saw nothing. Again he betook himself to his spade, and proceeded with new diligence to fill up the pit. This demeanour confounded and bewildered me. I had no power but to stand and silently gaze upon his motions.

The pit being filled, he once more sat upon the ground, and resigned himself to weeping and sighs with more vehemence than before. In a short time the fit seemed to have passed. He rose, seized the spade, and advanced to the spot where I stood.

Again I made preparation as for an interview which could not but take place. He passed me, however, without appearing to notice my existence. He came so near as almost to brush my arm, yet turned not his head to either side. My nearer view of him, made his brawny arms and lofty stature more conspicuous; but his imperfect dress, the dimness of the light, and the confusion of my own thoughts, hindered me from discerning his features. He proceeded with a few quick steps, along the road, but presently darted to one side and disappeared among the rocks and bushes.

My eye followed him as long as he was visible, but my feet were rooted to the spot. My musing was rapid and incongruous. It could not fail to terminate in one conjecture, that this person was asleep. Such instances were not unknown to me, through the medium of conversation and books. Never, indeed, had it fallen under my own observation till now, and now it was conspicuous and environed with all that could give edge to suspicion, and vigour to inquiry. To stand here was no longer of use, and I turned my steps toward my uncle’s habitation.

![]()

CHAPTER II

I HAD food enough for the longest contemplation. My steps partook, as usual, of the vehemence of my thoughts, and I reached my uncle’s gate before I believed myself to have lost sight of the Elm. I looked up and discovered the well-known habitation. I could not endure that my reflections should so speedily be interrupted. I, therefore, passed the gate, and stopped not till I had reached a neighbouring summit, crowned with chesnut-oaks and poplars.

Here I more deliberately reviewed the incidents that had just occurred. The inference was just, that the man, half-clothed and digging, was a sleeper: But what was the cause of this morbid activity? What was the mournful vision that dissolved him in tears, and extorted from him tokens of inconsolable distress? What did he seek, or what endeavour to conceal in this fatal spot? The incapacity of sound sleep denotes a mind sorely wounded. It is thus that atrocious criminals denote the possession of some dreadful secret. The thoughts, which considerations of safety enables them to suppress or disguise during wakefulness, operate without impediment, and exhibit their genuine effects, when the notices of sense are partly excluded, and they are shut out from a knowledge of their intire condition.

This is the perpetrator of some nefarious deed. What but the murder of Waldegrave could direct his steps hither? His employment was part of some fantastic drama in which his mind was busy. To comprehend it, demands penetration into the recesses of his soul. But one thi...