![]()

chapter 1

WALKER AND WEEKS

WALKER AND WEEKS began as the partnership of two young men from Massachusetts. Harry E. Weeks (1871–1935) was born in West Springfield on October 2, 1871. He attended the public schools there and then entered the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, graduating in 1893. He married Alice B. Tuggey in 1896. Weeks worked for several architectural firms in Massachusetts and had his own firm in Pittsfield for three years before coming to Cleveland in 1905 at the suggestion of John M. Carrere of the distinguished New York firm of Carrere & Hastings and a member of the Cleveland Group Plan commission.

Frank R. Walker (1877–1949) was born in Pittsfield on September 29, 1877. He proudly traced his family to the early seventeenth-century New England settlers in America. Walker’s father was an interior decorator in Pittsfield, a profession that no doubt helped influence Frank’s choice of architecture as a career. He attended the public schools of Pittsfield and graduated from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1900. Walker spent more than a year studying in the atelier of a Monsieur Redon, followed by another year in Italy. Upon his return to the States, he worked in the office of Guy Lowell in Boston, the prominent architect of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts and the New York County Courthouse. Walker subsequently became Lowell’s office manager in New York. After a brief time working in Pittsburgh, he also came to Cleveland in 1905 at the suggestion of Carrere. Both Walker and Weeks joined the office of J. Milton Dyer.

Dyer was a brilliant but uneven architect whose work in Cleveland covered an astonishing range, from the beaux-arts City Hall to the 1940 modernistic Coast Guard Harbor Station. However, for such important Dyer projects as the Cleveland Athletic Club, a remarkable tall building erected on the air rights above an existing structure in 1910–11, Walker was the principal designer and Weeks the job supervisor. And in later years Walker claimed credit for the design of Dyer’s most important public buildings—the Cleveland City Hall, the Lake County Courthouse in Painesville, Ohio, and the Summit County Courthouse in Akron.5 There is also reason to believe that Walker may have been responsible for the major residences out of Dyer’s office, the Edmund S. Burke and Lyman Treadway houses. In other works, Dyer’s best work was done while Walker and Weeks were in his office, and his significant work after 1911 was negligible. According to acquaintances of Dyer, his social habits became more and more erratic, sometimes keeping him away from the office for days and even weeks at a time, and in 1911 and 1912 many of the younger men left him. In 1911 Walker and Weeks formed their own partnership and set up an office at 1900 Euclid Avenue.

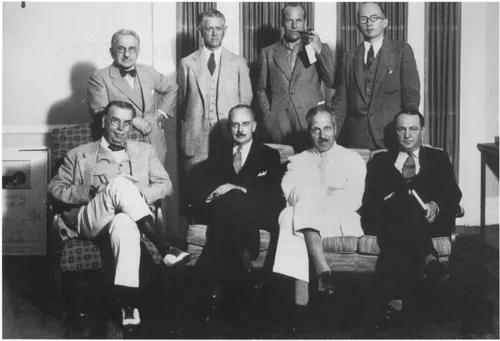

Walker, Weeks, and staff. Front row (from left): Frank R. Walker, Harry E. Weeks, H. F. Horn (?), and Dana Clark (?). Back row (from left): Claude Stedman (?), Byron Dalton, Armen Tashjian, and Dan Mitchell.

The partnership of Walker and Weeks grew during a period of rapid urban growth and booming industry and later blossomed during the high finance and big business of the 1920s. Banks, offices, and commercial buildings dominated their work for much of their career. Walker and Weeks met the extraordinary demands of complexity and largeness of scale by developing their departmentalized organization. (In fact, many good-sized businesses had fewer employees than they did.) Their annual volume of construction during the twenties was between $5 and $10 million (perhaps $102–$204 million in 1996–97).

In the heyday of the 1920s, the staff numbered sixty and there were eight partners in the firm. Besides Frank Walker and Harry Weeks, there were Claude Stedman, designer; Armen Tashjian, chief engineer; Byron Dalton, salesman and bank contact; Dana Clark, designer; H. F. Horn, later to be officer manager; J. Byers Hays, designer; Winifred Robblee, treasurer; and Dan Mitchell, chief draftsman and field supervisor. The office had its own staff photographer, Carl F. Waite. Other staff members were in charge of specification writing; drafting; structural, mechanical, and electrical engineering; architectural and construction details; field supervision; business management; and all of the manifold tasks required by the large firm.

According to Charles H. Stark, an architect who worked in the firm in the early 1930s, Walker and Weeks were “a strange combination.”6 Frank Walker, a big likable man, boisterous and sometimes earthy, was an excellent architect who knew good design. Harry Weeks was the “organizer in office politics” who kept the staff happy and together. Quiet and mild-mannered, a gentleman, who the men in the office always referred to as “Mr. Weeks,” he was “never seen with a pencil in his hand,” but he liked to stand at his office door and look out over the drafting room. Walker, on the other hand, came into the drafting room occasionally, sat down at someone’s drawing board, and sketched a few suggestions for changes. The respective roles of Frank Walker and Harry Weeks were also described in the article that appeared in 1914: “Mr. Weeks has always been more particularly devoted to the structural and practical phases of architecture and the immediate success of the new firm is in no small measure due to this accurate knowledge of the many-sided duties devolving upon him. Mr. Walker, on the other hand, is a designer of rare ability, standing high in architectural circles, and a member of the American Institute of Architects.”7

Most of Walker and Weeks’s jobs were brought into the office by members of the firm. Partners or teams specializing in certain types of buildings sought out the clients. Each partner had special skills and was a good architect in his own right, but each also acted as salesman, covering his specialties, whether banks, churches, offices, or factories. The partners handled the business relations, correspondence, and meetings between Walker and Weeks and the clients. The phenomenon of “marketing” by architects has been thought of as a relatively recent one, but their use of this strategy, in addition to the offering of complete planning services, is certainly one of the keys to the extraordinary success of Walker and Weeks.

The design process in the office was outlined in a paper by Claude Stedman, which begins with the premise that “Almost all modern buildings, apart from dwellings, form the skeleton and the enclosing shell of some extremely complex industrial or commercial operating organization.”8 The architects began a series of conferences with the client in order to gather data on the requirements of the building and, in a complex operation, of various departments and their relationships with each other. The development of program requirements could take several months, after which the design team began to study the development of the plan, including such factors as placement on a site, relationship of exterior to interior, the separation and connection of various functions, and the mechanical and structural systems. Again, in a complex building the development of the plan could take many months.

After the basic plan was approved draftsmen and architects began preparing working drawings in ink on linen, which required different sets for general floor plans, structural work, heating and ventilating systems, plumbing, and electrical engineering. At the same time, the exterior design was evolved through studies, sketches, and, if necessary, plaster models. The design and working drawings were handled by the job crew familiar with the particular type of building. If presentation renderings were required, J. Byers Hays, Wilbur Adams, and an unnamed artist of German extraction executed them. This entire design process took weeks or months or even an entire year and the efforts of a small team of up to thirty men, including the designers, draftsmen, and engineers in all of the fields.

The architects wrote the detailed specifications for the taking of bids and oversaw the contractual work. When construction began, they worked with the general contractor and the various subcontractors, who prepared shop drawings, sometimes numbering in the thousands, which had to be checked, often several times, by the architects. At the construction site, the architect’s field supervisor worked with the contractor on scheduling each task in order to avoid delays or conflicts among the subcontractors. This meant daily conferences, and frequently additional detail drawings were required.

The firm’s method was further explained in a proposal prepared by Byron Dalton for the Libbey Glass Company:

Our method of solving a problem such as the development of a plant of your type is perhaps different than that practiced by most architects and engineers. We could suggest the approaching of your problem in the following manner. To place our engineers and equipment men in your plant, working with the heads of various departments for your man in charge of construction and gathering all of the various requirements and details of every nature and then writing a program based on what we have found. We would then proceed to develop a plan reflecting your requirements so that your plant would operate in the most efficient manner.

On rare occasions we have found organizations that contain an individual who has at his finger tips all the information necessary upon which to base a program, but in most cases we have found it necessary to go to the various heads of departments. . . .

We retain a complete corps of engineers covering structural, both concrete and reinforcing, and all branches of mechanical work, which is quite exceptional except in organizations as large as ours, and we are sure that because of having these men within our own organization we can develop a much more homogeneous result than should it be necessary for us to call in various outside concerns to work in the different services which go to make up a complete building.

As to economical construction, our engineers and working drawing men have striven for years to keep down the cost of construction of our various types of building.9

2341 Camegie Building (Walker and Weeks office building), 1926.

For fifteen years Walker and Weeks’s office was located on the eighth floor of the 1900 Euclid Building, and then in 1926 the firm moved into a six-story office building which they had designed, at 2341 Carnegie Avenue. They occupied 9,700 square feet on the fifth and sixth floors; they leased the ground floor to a Lincoln Motor Car dealer and the intermediate floors to other tenants. Behind the classical front, a factory-like concrete-frame structure allowed ample clerestory light into the large fifth-floor drafting room, which measured 40 by nearly 120 feet. Along the sides of the room were the separate offices for designers, artists, the engineering department, specification writers, executives, and bookkeeping. The plan of Walker and Weeks’s office was described in The American Architect as being a direct expression of the operation of the firm:

Each job or commission is placed in charge of an executive and a designer with a job captain and suitable corps of draftsmen. Insofar as conditions permit, to simplify administration of the work, the six designers’ offices are located opposite those of the executives in charge, with the drafting force for the job between them. Contrary to the method employed in many large offices of keeping drawings in a file room in charge of a clerk, all drawings are maintained in files in the drafting room and made readily accessible to the executives, designers and draftsmen.10

There were three conference rooms for client meetings, and a library (20 x 40 feet) for the collection of historical style reference books that were constantly consulted by an academic architect. There were also sample rooms of materials used by both staff and the clients. For example, the marble and tile sample room was completely lined with 9-x-i2-inch marble slabs, comprising what was called probably the most complete collection of marble samples in the country, and the floor was composed of various kinds, patterns, and sizes of tile. Similarly, the window openings in the offices were fitted with different types of frames and sashes for inspection by clients. On the sixth floor were Walker’s 30-foot-long studio, a roof terrace, a bath, a storage vault, and a balcony overlooking the drafting room. In addition, there was a private dining room that seated about twenty; the staff signed up in the morning for lunch seating, the partners of the firm and employees with the most seniority having first choice.

The size of the organization meant that the firm often had dozens of commissions in the office at the same time, and the projects were allotted to the various designers. Among the chief designers were Dana L. Clark, Claude W. Stedman, J. Byers Hays, Edwin J. Truthan, and Elmer Babb. One designer could be responsible for the functional layout and another for the architectural elevations. Clark remained in the firm for thirty-five years and became head of architectural design, and Stedman, with Walker and Weeks for the entire life of the firm, beginning in 1914 became head of planning design. Nevertheless, according to Stark, Frank Walker maintained control and final approval of all work produced by the office.

Frank Walker himself clearly viewed the business of architecture as more than the designing of buildings. He saw it as the opportunity for shaping a whole environment, making architecture became a full-time professional activity. He was employed by the Cleveland City Plan Commission as its first professional adviser and collaborated with Robert H. Whitten in that capacity from 1918 to 1928. He was a member of the City Plan Commission for ten years when its principal work included studying the role of city planning in other cities and preparing a city plan for Cleveland, overseeing the development of the public works and Daniel Burnham’s Mall plan, and improving the streets and platting. Beginning in 1918 Walker was also an active member of the city plan committee of the Cleveland Chamber of Commerce. This committee reviewed public improvements, such as hospitals and public bath house designs, and promoted city and countywide schemes for rationalizing urban development, such as establishing local planning commissions, accepting land-use zoning, and adopting a uniform platting ordinance for Cuyahoga County.

Walker was interested in several undertakings in connection with what he called “pedagogical work related to architecture.”11 In 1921, when he was president of the Cleveland chapter of the American Institute of Architects, a group of architects led by Walker, Abram Garfield (son of President James A. Garfield), and others began a course in architecture at the Cleveland School of Art, which became the Cleveland School of Architecture in 1924. Walker served as a trustee of the school and a member of the faculty. The architects supported it financially until it became part of Western Reserve University in 1929.

Walker also acted as critic and patron of an atelier that became part of the John Huntington Polytec...