eBook - ePub

On Islam (Abraham Kuyper Collected Works in Public Theology)

- 400 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

On Islam (Abraham Kuyper Collected Works in Public Theology)

About this book

At the beginning of the twentieth century, famed theologian Abraham Kuyper toured the Mediterranean world and encountered Islam for the first time. Part travelogue, part cultural critique, On Islam presents a European imperialist seeing firsthand the damage colonialism had caused and the value of a religion he had never truly understood. Here, Kuyper's doctrine of common grace shines as he displays a nuanced and respectful understanding of the Muslim world.

Though an ardent Calvinist, Kuyper still knew that God's grace is expressed to unbelievers. Kuyper saw Islam as a culture and religion with much to offer the West, but also as a threat to the gospel of Jesus Christ. Here he expresses a balanced view of early twentieth-century Islam that demands attention from the majority world today as well. Essays by prominent scholars bookend the volume, showing the relevance of these teachings in our time.

Though an ardent Calvinist, Kuyper still knew that God's grace is expressed to unbelievers. Kuyper saw Islam as a culture and religion with much to offer the West, but also as a threat to the gospel of Jesus Christ. Here he expresses a balanced view of early twentieth-century Islam that demands attention from the majority world today as well. Essays by prominent scholars bookend the volume, showing the relevance of these teachings in our time.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

Theology & ReligionSubtopic

Christian TheologyCHAPTER 1

THE ASIAN DANGER1

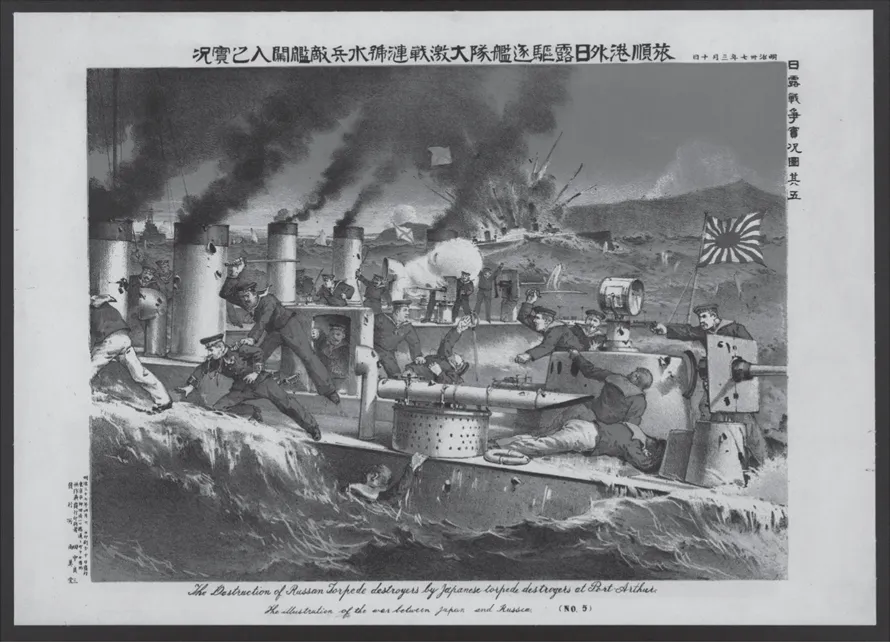

Destruction of the Russian fleet by the Japanese navy, 1904

Steaming into the splendid Bosphorus Strait from the Black Sea, with Europe on your right and Asia on your left, you cannot help but feel the historic contrast between these two mighty continents. While this difference seemingly had disappeared long ago, it now unexpectedly appears to have regained some of its former strength. Once again, as of old, Asia stands over against Europe—and, in part, America. Africa figures in world affairs only at its southern tip and along its northern rim, and will attain a self-standing position only in the future. For now, relations along its northern edge are developing along similar lines to those between Europe and Asia.

A single Asia lies adjacent to America on its east coast and Europe along its long western and southern edge—Asia with 830 million people, Europe and America together with their 485 million. This disparity in populations never posed any serious danger in past centuries because the slogan “Asia for the Asians,” or Asia fara da se, had never been raised. Yes, a steady stream of wild horsemen had thrown itself upon southern and eastern Europe from the steppes of central Asia—first under Attila, sometime later under Genghis Khan, then Tamerlane, and finally the Ottoman sultans. Under Attila these barbarians reached Orleans, and under the Moors all the way to Tours. But these hordes were driven by a craving for loot and revenge, which is why they wreaked havoc with equal cruelty in Asia as well. China, India, Persia, and even the caliphate suffered bitterly at their hand. A compelling legend from this period tells that after the combat in the Catalonian fields (451 AD), the spirits of the slain continued the battle in the air even while their bodies lay bleeding on the battlefield.2 But the long struggle against Attila, Genghis Khan, and Tamerlane did not pit Asia against Europe, but rather “barbarism” against civilization. Later, at Tours, it was Islam against Christianity, the Crescent against the Cross. When the Mongol conquerors took the Russian boyars and generals whom they had vanquished, stretched them out along the ground, laid planks over them, and proceeded to celebrate their Bacchanalia on that floor, this was the wrath of barbarians, not the proclamation of an autonomous and independent Asia.3 China and the Indian subcontinent, the sites where the vast majority of the Asian population resides, either remained outside the conflict or suffered under it themselves.

THE RISE OF ASIA

But now things have taken a turn. The unprecedented mastery Japan demonstrated over Russia has sent a shockwave through the heart of everything Asian, awakening a spirit of high expectations. A triumphal consciousness of their own power is rising among all its peoples. For four centuries now, Europe has held an irresistible mastery over Asia. The Ottoman Empire lost its strength while Russia penetrated into the very heart of Asia. England made itself master of the entire Indian subcontinent. Foreign powers imposed their law along the coasts of China. The Archipelago4 has long been in European hands. In Southeast Asia, Annam and Cochinchina fly the French tricolor.5 America has taken the Philippines from Spain. Any breath of resistance has been broken by force majeure. Time and again China has been chastised, even as Germany installed itself as a new power in Kiao-Chau.6 Weakness acquiesced to strength. Poorly armed and poorly organized, Asia has been unable to withstand either Europe or the United States.

That mood of resignation has since made way for one of near-recklessness. Compared to China, Japan is quite modest in size, yet it waged a life-and-death struggle with the northern colossus. It had developed its power both on land and at sea so remarkably that the battle, once joined, quickly brought about Russia’s total defeat. Japan has as good as annexed Korea and essentially runs things in Manchuria. Economically it is developing rapidly. It has plenty of European capital invested at reasonable rates of interest. Its lower wage structure makes it quite competitive with American and European industry. In technology it advances year by year and is already competing with Europe in the fields of the natural sciences and scholarship. The center of world politics has already moved, in significant degree, from the Atlantic to the Pacific, and the digging of the Panama Canal will only underscore this development. Europe itself has supplied Japan with the knowledge, the benefit of experience, and even some of the means for its amazing development. The Japanese have adapted most competitively in higher education, military camps, and naval yards, and it is already clear that in naval preparedness and military development they trail neither England nor Germany.

In tactics the Japanese have schooled old Europe. They have the threefold advantage of an extremely sober sensibility, high patriotic enthusiasm, and cool nerves. History records that Genghis Khan’s hordes swarmed the steppes with nothing but some dried meat and cheese in their knapsacks. Although the Japanese commissary opted for better provisions, the soldiers’ frugality did not trail the mounted warriors’, and it proved equal to the severest hardship. Their enthusiasm was equally notable. The contempt for death with which the Japanese battalions assaulted the strong fortifications of Port Arthur manifested more than heroic courage.7 Their unwavering willingness to devote their very lives to storming the barricades demonstrated that a high patriotic conviction had set these men afire. No sacrifice for the Japanese fatherland was considered too severe, a sentiment elevated further by the religious concept of ancestor-worship.

It is a mistake to think that only the honor of Japan as a country was at play here. Equally strong was Japan’s strong antipathy toward the alien western element, closely connected with East Asian self-regard. Practically speaking this was manifest in their steady nerves. That quality is already of some import in combat on land, but especially in modern naval warfare it is, if not decisive, certainly of disproportionate weight. This is the case for two reasons. Those who are high-strung are always on the lookout for a much-needed stimulus, such as the Russian with his vodka. And a nervous commander of a modern battleship, say, is easily thrown off guard by the shriek and explosion of shells. Japanese soldiers and sailors suffer no such qualms. Under heavy artillery fire they remain quiet and calm—resorting to alcohol for stimulation and bravado is entirely foreign to them. Psychologically, therefore, the Japanese have the advantage in any battle on land or sea where the numbers and odds are even. It is this double psychological edge that explains Japan’s imperturbable, machine-like progress through its recent unbroken series of triumphs.

The Russo-Japanese War has revealed something hitherto unknown. We Europeans have long simply assumed that, all other things being equal, Asians are far inferior to us. It is now evident that the Asian is at least our equal, if not in many respects our superior. This discovery has both frightened us and rapidly resounded throughout Asia as a voice of future liberation. In the eyes of the Asian, the white man has lost his aura of superiority. The realization that Asians can match us everywhere has taken root in China, in the heart of Asia, and even in India. They feel weak for the moment because of their lack of readiness, but now foresee the prospect of throwing off their inferior status. What Japan can do they feel they can too, and so they are already searching for a way to follow Japan’s lead. Unexpectedly the morning star of a wonderful ideal has arisen over Asia. It might not yet be clear as to how to achieve that ideal, but Japan, mighty Japan, has stepped up and is to be followed as leader and teacher. This task Japan has taken upon itself. It did not wait to be summoned but, on its own initiative, gave expression to this slumbering expectation.

Now China has awakened, with its agents starting to stream out all over the place. The Chinese are ready to shed their silk robes and buckle up the harness. China is much, much larger than Japan and will therefore move a little slower, but move it will. In this regard, predicting the future is not difficult: once launched, China will surpass the Japanese not only in numbers but also in manpower and higher development. It will take time, of course, before signs of a more vigorous life emerge also in South Asia. Japan has guaranteed England its Indian possessions in advance, so for now these lie outside the scope of Japan’s aspirations.8 But the principle of “Asia for the Asians” is finding traction there without any Japanese propaganda. Though it is somewhat slower than in Europe, there is communication across Asia, particularly between Chinese and Indian Buddhists. Even if the process takes fifty years, what is half a century in the transformation of world history? Such a movement, once commenced, will advance irresistibly unless—and this is also possible—in a later phase a counter-action against Japan’s hegemony arises out of Europe and America. Even that would not delay the danger for long. Once awakened China can develop a tremendous power that will overcome any resistance, even without Japan’s help. Economically, great treasures lie hidden in this giant empire, and none less than Gordon declared in the war with the Boxers that he knew of no better soldier than the Chinese.9

CONCERN FOR THE COLONIES

The foregoing is not intended to arouse fear and anxiety but only to prevent surprise over this outcome. For the colonial powers in particular, which are the first in line, the emergence of this danger will only be a matter of time. Tensions can be softened somewhat if people try not to suppress but indulge this rising movement of Asian blood to a certain point. Bear in mind that the Chinese in particular have nomadic tendencies; they tolerate tropical climates better than do the Japanese; and Li Hongzhang has already seriously protested the unequal position reserved for the Chinese in the Dutch colonies.10 Even if the Japanese are less inclined to migrate south in large numbers and for the moment have found areas for colonization in Korea and Manchuria, a few of them have started settling more in other regions, and whoever claimed that each Japanese is sort of an agent for and bearer of a national idea is certainly not far from the truth. The Philippines are already home to 70,000 Japanese.

In and of itself it would be silly to argue against a reassertion of independence on the part of Asian nations that have attained sufficient maturity for autonomous development. However difficult it will be for the colonial powers, from a higher perspective it should be cause for rejoicing when millions arise from what appeared to be their sleep of death and aspire to greater vitality. The question is, rather, whether the Asian movement will be satisfied once, sooner or later, this goal has been achieved. Undoubtedly a kind of Asian Monroe Doctrine will become fashionable, at least in East and South Asia.11 For now, we must take account of the struggle of economic interests which will probably be the first order of business. Some Chinese markets have boycotted American goods for quite a while already, and statistics indicate serious Japanese attempts to compete with European imports into China.

Over the past thirty years, high-level politics have increasingly focused on the issue of débouchés [expansion] with respect to European and American industry. It is too much to say that economic issues have wholly dominated international politics, since other matters have been addressed as well, particularly those driven by national and imperialistic motives. Yet it is beyond dispute that the international struggle has been primarily of a one-sided materialistic character. Consider only the insatiable desire for colonial possessions, the parceling out of Africa as booty, the recurrent tariff wars, and, finally, the fermentation in Europe that threatened war in Morocco.12 Most certainly Japanese and Chinese industry will catch up to us, particularly in the areas of technical skill and taste. Combined with the efficient use of capital, their lower wages will give these countries a competitive edge that will prove difficult for us to overcome. At present there is not only a movement afoot to drive us out of Japan and China, but also to compete with us in European markets. It is easy to see that this will lead to conflict; Europe and the United States will not be driven out without a fight. Similarly, it is most unlikely that the United States will sit quietly by while its states are inundated by the Chinese and Japanese. American statesmen are busily engaged in discussions regarding the erection of a legislative dam to forestall these developments. The ban on Japanese school children in California is a prelude.13

But let us assume for a moment that even this issue can be peacefully resolved. Then the serious question presents itself: will an awakened and very powerful Asia, which already commands not only a myriad of troops but also a world-class naval fleet, remain a peaceful neighbor to Europe nearby and to the United States overseas? In its eras of former power Asia showed a strong tendency to carry its standard far beyond its borders. Persia threw itself upon Greece, Attila ravaged half of Europe, Genghis Khan destroyed the Russia of the day and was even seen in Bohemia and Poland. Islam conquered North Africa and Spain, while the Turks were only halted outside of Vienna. Will an Asia resurrected in power have cast aside this past tendency? Will there be no thought of reprisals for Europe’s centuries-long affliction of Asia? Apart from all this, shall not the difference in fundamental type, and therefore in outlook and interests, between East and West remain a fateful source of ongoing entanglement and friction? Will not a desire to determine who is stronger and thus establish the terms of mutual relationship provide a constant source of tension building up to a gigantic struggle? Even though this change in relative strength between these two powers still lies in the distant future—many years even, likely an entire generation—it would be highly imprudent to ignore the implications of this coming reality. Forty years ago no one would have believed that a Japanese powerhouse would emerge within one generation, yet this undeniable fact stands visibly before us.

With respect to its colonies, the Netherlands in particular must be clearly aware of the demands placed upon it by the altered conditions in the East. Russia is rebuilding its fleet, and should it ever decide to engage the East in hostilities in the future, any other power from the West will have to approach the field of battle by sea. In any such operation the Dutch archipelago is the great strait through which an eastern-bound European fleet or a western-bound Asian fleet will have to find passage. In the recent war this posed a real danger for the Netherlands, which felt compelled to preemptively strengthen its naval power in the archipelago. Naval hostilities could easily have erupted there. Apart from this, however, many wartime conditions give rise to actual inconveniences and disputed points of law: postal and telegraphic communication, the furnishing of coal and provisions, the sheltering of pursued ships, and the harboring of damaged war vessels—the list could go on. Engaging such activities could quite innocently irritate one of the belligerent powers, give rise to complaints, and thus set the stage for further complications.

The great distance separating mother country and colonies exacerbates this danger for us. If Japan, in particular, were involved in such a future war so as to activate its alliance with England, it is highly doubtful whether a Dutch warship from the mother country could reach the archipelago. Although telegraphic correspondence with Batavia, independent of the English lines, seems pretty well assured, no ship could pass through the Red Sea without falling into enemy hands. In addition, no warship of five to six thousand tons can steam around the Cape owing to the lack of our own coaling stations there. Recall we ceded by treaty our past possessions on the Gold Coast of West Africa, in St. George d’Elmina. Even if we dismiss the rumors currently swirling in the press that ascribe to Japan ominous plans against our colonies, we must acknowledge that any such aggression would place the Netherlands in a very unsafe position, even in a war in which it was not itself involved. While we cherish the hope that the second and a subsequent third peace conference will more sharply delineate the rights and responsibilities of neutral powers in times of naval warfare, even this will not completely ensure the Netherlands’s position in the East.14 In fact, the Netherlands would show unpardonable shortsightedness in its colonial policy if it were to be naïve to the dangers of the newly arisen situation. Isolation can harbor strength, but it can also foretell power’s demise.15

EASTERN RELIGION AND THE WESTERN PRESENCE

Much weightier in import, if of less immediate interest, is an entirely different question: whether the coming struggle might not also involve the religious opposition between paganism and Christianity. There are good reasons to wonder. It cannot be denied that Christian missions in the East continue to be a thorn in the side of the native people. An Eastern woman of noble birth who, for all her native origins, highly valued being seen as fully modernized, once told me at the close of a particularly violent attack on Christianity: “The biggest bane of my country are these miserable missionaries. Oh, I would love to have them in front of me! I’d take a big knife and slit their throats like sheep.” If this represents the opinion of a woman of high society parading her modern attainments, then what must pass in the heart of the commoners who are still attached to their ancestral religion?

The enmity toward these missions would proba...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- General Editors’ Introduction

- Editor’s Introduction

- Introduction: The Western Islamic World at the Dawn of the Twentieth Century

- Introduction: Abraham Kuyper’s View of Islam: The Dutch Setting

- Chapter 1: The Asian Danger

- Chapter 2: Constantinople

- Chapter 3: Asia Minor

- Chapter 4: Syria

- Chapter 5: The Holy Land

- Chapter 6: The Enigma of Islam

- Chapter 7: Egypt and Sudan

- Chapter 8: Algeria and Morocco

- Chapter 9: Spain

- Chapter 10: Conclusion

- Afterword: By What Magic Did Muhammad …?: The Missiological Implications of Abraham Kuyper’s Observations on Islam

- Bibliography

- About the Contributors

- List of Illustrations

- Subject/Author Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access On Islam (Abraham Kuyper Collected Works in Public Theology) by Abraham Kuyper, James D. Bratt in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Christian Theology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.