This is a test

- 680 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

From the beginning to 1940. Written for both students and adults. The author intersperses the history with many brief, interesting biographies of famous people, and at the end of each chapter he quotes briefly from a famous writing of the era, blending a medley of elements into a comprehensive historical composition that is at once brilliant and fascinating. A story of the Church unparalleled in its scope, depth, variety and impact, and a book all Catholics should read.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Church History by John Laux in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Christian Denominations. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Theology & ReligionSubtopic

Christian DenominationsSECTION III

The Church in Modern Times, from the Protestant Revolt to the Present Day, A.D. 1517-1930

FIRST PERIOD

From the Protestant Revolt to the French Revolution 1517-1789

CHAPTER I

LUTHER AND LUTHERANISM

Luther's Early Years.—Martin Luther was born of poor parents at Eisleben (Saxony) in 1483. He received his elementary education at Mansfeld, Magdeburg, and Eisenach. At Eisenach young Martin was a "poor student," that is, a boy who lived rent-free and attended school without paying tuition, and for his board sang as a chorister in the church to which the school was attached. At eighteen he entered the University of Erfurt and took the various degrees in an unusually brief time. His father, whose fortunes had in the meantime improved, wished him to study law; but his fond hope of one day seeing his talented son a famous lawyer, was frustrated. Martin, who was harassed with constant fear for his soul's salvation, suddenly resolved to leave the world and become a monk. Without consulting his parents or notifying them of his intention, he entered the convent of the Augustinian Hermits at Erfurt (July 17, 1505).

In the convent Luther did not find the peace of soul and the assurance of salvation which he had come to seek. He fasted and scourged himself, practiced all kinds of mortification, and made frequent general confessions. All to no purpose. He advanced to the priesthood in 1507, received the degree of doctor of theology in 1512, and in the same year was sent by his superior to teach philosophy and Sacred Scripture at the newly founded University of Wittenberg. He plunged headlong into his duties; but no amount of work could allay the tumult of his morbid conscience. In 1510 he was despatched to Rome on some business connected with his Order. While there he made a general confession, hoping it would bring him peace. Just the contrary happened: he was more discontented than ever with the state of his soul. All his efforts to attain holiness seemed to him of no avail. His fear of hell and eternal damnation almost drove him to distraction. The prescriptions of the Rule became an intolerable burden to him. He fought hopelessly against the temptations that assailed him. Tiring at last of this constant warfare, he persuaded himself that good works, since they had failed to give him the desired inward peace, were useless for salvation; that faith alone justified before God; that God's pardon could be won only by trusting to His promises. This false view of justification led to another equally false: that man has become, in consequence of Original Sin, incapable of willing or doing anything good: all his acts are sins; he became a rotten tree by Original Sin, and cannot bear good fruit. These doctrines, which he believed he had found in the Epistles of St. Paul, and which became the fundamental dogmas of the New Gospel, were publicly taught by Luther in his lectures at Wittenberg as early as 1516, if not earlier. In 1517 an occasion presented itself of giving them still greater publicity.

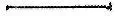

LUTHER AS A MONK

Luther's Ninety-five Theses.—Pope Julius II (d. 1513), anxious to secure funds for the building of St. Peter's, had proclaimed a Plenary Indulgence throughout Europe which all could gain who confessed their sins, received Holy Communion, and contributed according to their means towards the erection of St. Peter's. Under his successor Leo X, the Archbishop of Mainz, Albrecht of Brandenburg, undertook to publish the Indulgence in Germany. Half of the contributions was to go to him to pay a tax which he owed to the Holy See. When the Dominican John Tetzel, who had been commissioned by the Archbishop to preach the Indulgence in Saxony, approached Wittenberg, Luther, who had long since thrown indulgences along with all other good works overboard, nailed his famous Ninety-five Theses, most of which were directed against indulgences, on the door of the Castle Church of Wittenberg (Nov. 1, 1517), where everyone could see and read them. He offered to defend them against all comers. The Theses were drawn up very skillfully and in a style likely to deceive the unwary. Many of them were quite orthodox, while not a few were clearly opposed to the teachings of the Church on Indulgences and Purgatory.

MICHELANGELO'S DESIGN FOR THE NEW ST. PETER'S

The publication of the Theses aroused great commotion in Germany. Everyone wanted to read them. In less than a fortnight they were known throughout the country. Within a month they had been heard of all over western and southern Europe. All who were dissatisfied with the Papacy, especially many humanists, hastened to assure Luther of their approval. Tetzel himself, Professor Eck of Ingolstadt, and other Catholic theologians published very learned rejoinders; but while the defenders of the faith were wasting their time preparing erudite dissertations which only a few would read, Luther was employing his extraordinary powers as a popular orator and writer to win support. He succeeded beyond his expectations. In a short time he had secured an enormous following, most of whom, however, regarded him merely as a reformer anxious to put an end to abuses in the Church. The Elector Frederick the Wise of Saxony and Luther's own Provincial Staupitz openly sided with him. This increased Luther's self-confidence.

Intervention of Rome.—Informed by the Archbishop of Mainz of the disturbance in Germany, Pope Leo X did not take the matter very seriously. He thought that at worst it was only a dispute between two rival Religious Orders. A letter which Luther had written to him, and in which he had declared: "In your voice I recognize the voice of Christ, who lives in you and speaks through you," seemed to justify this view. He contented himself with asking the General of the Augustinians to keep his monks quiet. When the Emperor Maximilian finally succeeded in opening Leo's eyes to the gravity of the situation, Luther was summoned to Rome. At the request of Frederick the Wise this order was retracted, and a meeting was arranged between the Papal Legate, Cardinal Cajetan, and Luther at Augsburg in the autumn of 1518. The interview produced little effect. Luther refused to admit that the merits of Christ and of the saints constitute the treasury out of which the Church takes her indulgences, and insisted that the sacraments work merely in proportion to the faith with which they are received. He promised, however, to be silent if his opponents also remained silent. Before leaving Augsburg, Luther published two appeals—one from the Pope ill-informed to the Pope well-informed, and another to a General Council. The next year, however, he was induced by the Papal Chamberlain Charles von Miltitz to write a most respectful letter to the Pope, assuring him of his loyalty and devotion. How sincere these protestations were, may be judged from the fact that three days after he had written to the Pope, he wrote to Spalatin, the chaplain and private secretary of Frederick the Wise: "I am not sure whether the Pope is anti-Christ himself, or only one of his apostles."

The Leipzig Disputation.—In a controversy between Luther's adherent Andrew Carlstadt and Professor Eck of Ingolstadt, several of Luther's tenets were branded as heretical by Eck. Accordingly, when Eck and Carlstadt met in public debate in the ducal palace at Leipzig (June-July, 1519), Luther also presented himself in order to take part in the disputation. In the heat of debate Luther went so far as to defend the teachings of John Hus, which had been condemned by the Council of Constance. He had thus, as Eck forced him to admit, accused a General Council of teaching error. All those present, especially Duke George of Saxony, were highly indignant. Luther was branded as a heretic. Eck left Leipzig triumphant, and Luther returned to Wittenberg deeply mortified and depressed. The disputation had, however, served to give him and his theories the notoriety he desired, and won for him the man who was to be his ablest supporter, the learned, but pliant and vacillating, Philip Melanchthon, professor of Greek at Wittenberg.

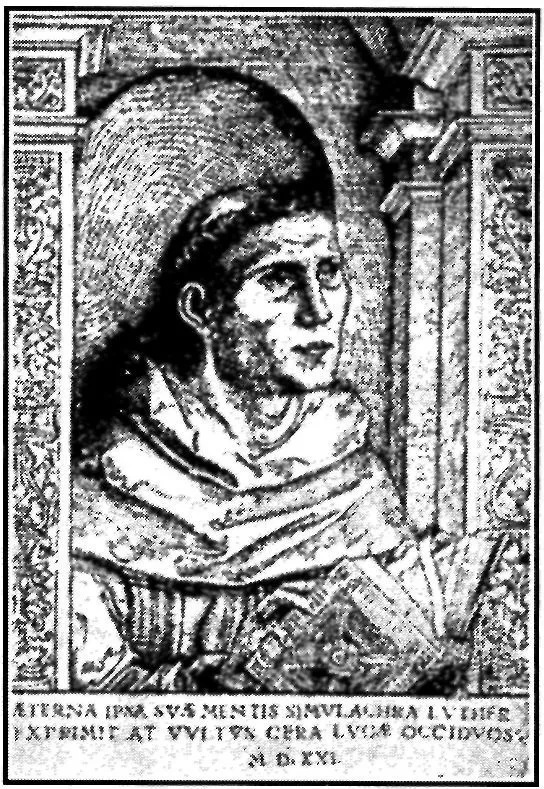

Under the Ban of the Church and the Empire.—In the meantime Luther's doctrines had been thoroughly examined in Rome. A Papal Bull (Exsurge Domine) condemned forty-one of Luther's propositions, interdicted his writings, and threatened him with excommunication unless he retracted within sixty days.

The action of the Pope came too late. Luther had passed the stage when he feared even threats of excommunication. He posted a notice inviting the students and people of Wittenberg to witness the burning of the Bull, which took place Dec. 10, 1520. He then threw himself with renewed ardor into the struggle. In a series of pamphlets—"An Address to the Nobility of the German Nation," "On the Liberty of a Christian Man," "On the Babylonian Captivity of the Church of God"—written in a terse and popular style, he exposed the abuses rampant in the Church, but also attacked the divine foundations of her constitution. He declared that the priesthood and the episcopal office must be done away with; that the secular power must have the right to decide also in spiritual matters. "He appealed to the cupidity of the princes by offering to make them the heads of the Church in their own states if only they threw off the Pope, to the discontented nobility and peasantry by dangling before their eyes the wealth which would be ready for distribution among them if bishoprics and monasteries were suppressed, and to the university students and professors by proclaiming that he was the champion of liberty, who would save them from the ignorant rule of the Scholastics" (MacCaffrey).

Luther had proved himself an obstinate heretic. The Church had done her part to reclaim him. Nothing remained but an appeal to the secular power.

Charles V had been elected emperor in 1519, and had been crowned at Aachen in the following year. As ruler of Spain, the Netherlands, Germany, and the greater part of Italy, the young Emperor, who was devoted heart and soul to the Catholic Church, might have easily put an end to Luther's movement had he not been handicapped by revolts in Spain, by wars with France, and by the Turkish invasion of the Empire, and, above all, by opposition within the Empire itself. On January 22, 1521, he opened his first German Diet at Worms. Luther was summoned under a safe-conduct to appear and stand trial. He was asked whether certain books had been written by him and whether he was prepared to maintain or to abjure what he had written against the Catholic faith. He answered the first question at once in the affirmative, but asked time to prepare an answer to the second. When he again appeared before the assembly—he had in the meantime received assurance of support from Frederick of Saxony and other German nobles—he refused to retract his doctrines unless they could be shown to be false by Scripture and reason. Thereupon Luther and his adherents were placed under the ban of the Empire; their writings were to be destroyed, and all books were in future to be censored before publication. Luther was ordered to leave Worms and to return to Wittenberg. His safe-conduct was to expire in twenty-one days. Then he was liable to be seized and executed as a heretic.

TITLE OF THE BULL AGAINST LUTHER

LUTHER AT THE DIET OF WORMS

To save Luther from the possible consequences of the ban, the Elector of Saxony ordered some knights to seize him on his way and bring him to the Castle of the Wartburg near Eisenach. The report was spread that Luther had been slain by emissaries of the Pope, and that his body, pierced with a dagger, had been found in a silver mine. Luther remained ten months in the Wartburg During this time he began his German translation of the Bible, which was completed in 1534.

Luther translated the Old Testament from the Hebrew, the New Testament from the Greek. As he was himself neither a Hebrew nor a Greek scholar of any note, he was much indebted to Philip Melanchthon for assistance. Luther was by no means the first German Bible translator, nor can his translation be called an independent work from the original Hebrew and Greek: there is no doubt that he had the old Catholic German Bible of 1475 before him when making his translation. He did not scruple to do violence to many passages in the original in order to make them harmonize with his own heretical views. Thus, to bolster up his false doctrine of justification he added the word "alone" after the word "faith" in Rom. 3, 28. He omitted the so-called deutero-canonical books—Tobias, Judith, Wisdom, Ecclesiasticus, Baruch, 1 and 2 Machabees and parts of Esther and Daniel—from the Old Testament, and from the New Testament the Epistle of St. James, which he contemptuously called "a straw Epistle," because it teaches that "faith without works is dead."

Private Judgment in Action.—The results of Luther's revolutionary teachings—his denial of free will, his assertion of the complete corruption of human nature by Original Sin, his doctrine of justification by faith alone, his stand on the Scriptures as the sole authority in religious matters, his wild onslaughts on all authority, both ecclesiastical and civil—soon made themselves felt. Tradesmen and day-laborers publicly interpreted the Bible, which had suddenly become intelligible to everyone. At St. Gall, in Switzerland, a crowd of people left the city and directed their steps to the four quarters of the globe to announce the kingdom of God to the nations: didn't the Bible say: "Go, teach all nations and preach the Gospel to them?" Thomas Münzer of Zwickau concluded from the Scriptures that all Christia...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Copyright Page

- CONTENTS

- AUTHOR'S PREFACE

- Introduction

- SECTION I The Ancient Church to the Beginning of the Pontificate of Gregory the Great, A.D. 590

- SECTION II The Church in the Middle Ages From St. Gregory the Great to the Protestant Revolt, A.D. 590-1517

- SECTION III The Church in Modern Times from the Protestant Revolt to the Present Day, A.D. 1517-1933