This is a test

- 172 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Wonder of Guadalupe

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This relatively short book is widely regarded as the best on the apparition of Our Lady in 1531 in Mexico City. Tells the complete story: From the Conquest of Mexico and the conversion of the Aztecs through the development of the devotion and on into the modern era. An enthralling story and an essential devotion for our times!

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Wonder of Guadalupe by Francis Johnston in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Christian Denominations. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Theology & ReligionSubtopic

Christian DenominationsChapter 1

THE CONQUEST OF MEXICO

THE story of Guadalupe really begins with the arrival of the Spanish forces in Mexico in 1519 under their brilliant commander, Captain Hernando Cortes. As the soldiers penetrated the vast hinterland, across the sandy deserts and expansive green plains, broken by rugged mountains and deep gorges flashing with rivers, they were astonished at the relatively high level of culture attained by the Aztec civilization they encountered. In many respects, the standards of the Aztecs approached those of Spain itself.

The country of some ten million inhabitants was divided into thirty-eight provinces populated by various tribes which had been subjugated and incorporated into the Aztec Empire. Each province was ruled by a governor, and these dignatories, together with the chief nobles and under the ruling authority of the Emperor in Tenochtitlan (which became Mexico City after the Spanish conquest), controlled the army, levied taxes and directed the interchange of trade and commerce. There were accomplished mathematicians, astronomers, architects, physicians, philosophers, craftsmen and artists, while the judicial system bore a striking resemblance to the pattern existing in many European countries. Education began at a very early age, but reading and writing were limited to a pictograph system which was similar to the ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics.

Despite these impressive achievements, the Aztecs were surprisingly backward in some fields of knowledge. They were ignorant of the physical laws that had been demonstrated by the Greeks some 2,000 years earlier. Their mathematicians had no knowledge of experimental science. Nor were they familiar with the wheel, animal traction, or the vaulted arch.

The Aztec towns were usually built around a stone pyramid-shaped temple where they held their religious ceremonies. Nearby would be a large plaza for communal gatherings and a market-place, invariably ringed by prominent stone dwelling-houses belonging to the upper classes, with spacious rooms and interior patios. In some towns, the Spaniards found that their buildings had been erected on raised wooden platforms as a protection against floods. The outskirts were inhabited mostly by the lower classes and consisted of thatch-roofed, windowless houses with walls of wattles smeared with mud. There were several heavily populated cities in the country at the time; Tenochtitlan alone counted 300,000 inhabitants.

Like many contemporary nations in Europe and Asia, the Aztecs had developed a rigid caste system. The highest level consisted of the Emperor, the chief nobles, the chief priests and the judges. Next came the nobles of lower rank who served as administrators. Below them were the freemen, the approximate equivalent of our present-day middle class, who constituted the greater number of the population. Under these came the unskilled laborers and the very poor, while at the bottom rung of the social ladder were the slaves.

Agriculture was the leading industry of the country and corn was the chief crop, while others of lesser importance included beans, tomatoes and various fruits in addition to cotton and tobacco. The maguey cactus plant was particularly valued since many useful products could be derived from it. The sap could be fermented and used as a kind of beer, the thorns converted to needles, while its fibre could be twisted into string and rope or woven into material suitable for clothing. Because of their basic importance to the Aztec economy, both corn and the maguey plant were worshiped as goddesses.

This seemingly advanced standard of civilization was tragically blighted by a religion which sank to some of the worst excesses of superstition. It is difficult for the modern mind to fully comprehend its horror, despite our familiarity with such barbarous modern atrocities as the concentration camp and the practice of “total war.” The Aztec rituals sprang from a compulsive instinct to attract those natural forces which were beneficial to humans, and to repel those that were malign. Most of these forces, such as the sun, rain, wind, fire and so on, were personalized as gods and goddesses, and idols of these deities were worshiped in the massive pyramidal temples.

The Aztecs felt themselves under a compelling obligation to offer human sacrifices to these gods, either in atonement for some physical calamity, such as a pestilence or earthquake, or to forestall an expected misfortune. For instance, since the Aztecs regarded themselves as the “people of the sun,” they felt driven to supply this divinity with a regular “nourishment” of human blood, for fear that he might no longer appear on the eastern horizon.

The victims of these sacrifices were most frequently slaves or prisoners of war, and the method of immolation was frightful in the extreme. Tearing out the hearts of living victims by black-robed, long-haired, chanting priests was a relatively merciful death compared to being flayed or eaten alive, and even worse horrors that do not easily lend themselves to words. The killings were on a considerable scale, and occasionally reached thousands in a single day as failure to influence the gods generated a frenzy of slaughter. The bloody hecatomb was actually a horrific inversion of the Christian sacrifice, in which the blood shed by the hapless victims was held to redeem the life of a god, and the continuous application of this human sacrifice was regarded as a solemn duty for the welfare of the people.

The sacrifices were carried out in the great stone temples of each town or city. The mightiest god was Quetzelcoatl, the feathered or stone serpent, to whom many thousands were sacrificed alive each year. Curiously, the name also applied to a great prophet who had reputedly appeared in the dim past and preached a semblance of Christianity which gradually became intermingled with the tenets of paganism. It was widely believed that he would one day return and redeem Aztec society. Another leading deity worth mentioning was the god of war and of the sun, Huitzilopochtli. A frightful temple had been erected in his honor at the town of Tlaltelolco, close to Tenochtitlan, and which the Spaniards found to be a veritable charnel-house. At the inauguration of this temple in 1487, some 20,000 warriors were sacrificed on its altars at the command of the Aztec Emperor, Auitzotl, to appease this monstrous divinity.1 Perhaps it is significant that the site of this edifice was to play an important role when the healing hand of Christianity began to spread over the land.

In view of what was to come, it is worth mentioning here the great mother god, Tonantzin, whose temple had once stood on the summit of a small hill named Tepeyac, about six miles to the north of Tenochtitlan. A statue of this grim goddess in the Anthropological Museum in Mexico City today vividly conveys the truly chilling nature of the Aztec mentality. Her head is a combination of loathsome snakes’ heads and her garment a mass of writhing serpents. Like the idols of other divinities in the same museum, Tonantzin projects a visage of fathomless grief from her sightless eyes, as if in perpetual mourning over the self-slaughter of her children. Even the nearby idol of the god of joy, Xochipilli, wears a countenance of extreme desolation. Not without reason did the Spanish missionaries, who arrived on the heels of the conquerors, regard this terrible creed as an indication of satanic infestation.

At the time of the Spanish invasion the Emperor of Mexico was the great Montezuma II, who had ascended the throne in 1503. He was a highly superstitious, philosophical man, inclined to witchcraft, and with a vicious streak of tyranny. His harsh rule was bitterly resented by the outlying subject tribes of the Empire and rebellions were frequent. Montezuma’s sinister nature, however, also harbored a deep respect for omens and portents, and these seemed to multiply as reports of strange ships being sighted far out to sea reached his attentive ears. Gloomily, he listened to his soothsayers predicting the eventual overthrow of this kingdom by white men from across the ocean.

In 1509 his sister, Princess Papantzin, had an extraordinary dream which seems to have had a decisive influence on the fatalistic Emperor. In that year, she fell seriously ill and lapsed into a coma. Believing her to be dead the Mexicans laid her in a tomb, but hardly had they done so when they were startled to hear her crying out to be released from the coffin. Upon recovering, she related the substance of a profound dream she had just experienced. It seemed that a luminous being had led her to the shore of the boundless ocean and that as she gazed out to sea, a number of large ships materialized with black crosses on their sails which corresponded to the black cross on her guide’s forehead. The princess was informed that the vessels were bringing men from a distant land who would conquer the country and bring the Aztecs a knowledge of the true God. The brooding Montezuma read the doom of his Empire in this dream and the fate of Mexico was possibly all but sealed years before the first brightly armored Spanish soldiers waded ashore from their anchored galleons.

The Mexicans were overawed by the thundering canons and muskets and the superb battle tactics of the advancing Spaniards. Their cavalry seemed invincible to a race that had never set eyes on a horse. To ensure that the white soldiers were indeed the ones seen in his sister’s dream, Montezuma had one of the Spanish helmets brought to him, and saw for himself the fateful black cross emblazoned on the front. He consulted with his nobles, and after an indecisive meeting decided to try and buy Cortes off with lavish gifts. The latter’s forces had meanwhile been encountering a growing number of regional tribes who detested the iron rule of the Aztecs and yearned to overthrow them. Quickly sizing up the situation, Cortes promised to help them provided they would join forces with him. Soon a growing army of Spaniards and Mexicans were battling their way across the rugged country towards Tenochtitlan. After each victory, their enemies were persuaded to join forces with them in their march on the Aztec capital.

Seeing the balance of fate relentlessly tilting against him, Montezuma felt he had no choice but to await the arrival of Cortes and negotiate a settlement. The Spaniards and their Indian allies advanced cautiously on the city, grimly aware of Montezuma’s reputation for treachery, and Cortes kept a wary eye on his new allies as well, for he could not yet be entirely certain of their loyalty.

A map showing the Mexico City area as it was in 1531, the year of the apparitions. The lakes have been drained, except Lake Xochimilco. Mexico City now includes all the towns shown here.

An artist’s conception of Tenochtitlan, as Cortez found it in 1519. It is now part of Mexico City.

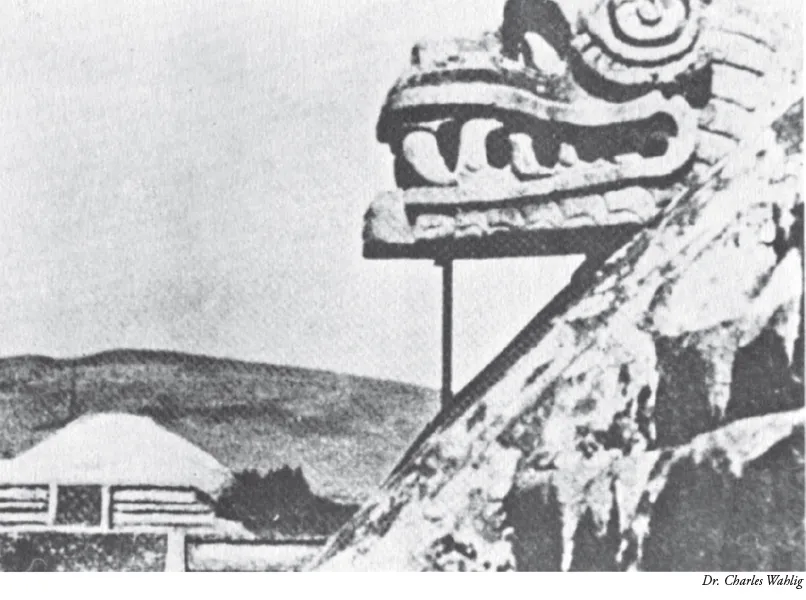

A partial view of the Temple of Quetzalcoatl, the Stone Serpent, with the Pyramid of the Sun in the background.

A reconstructed Aztec wall complete with gargoyles.

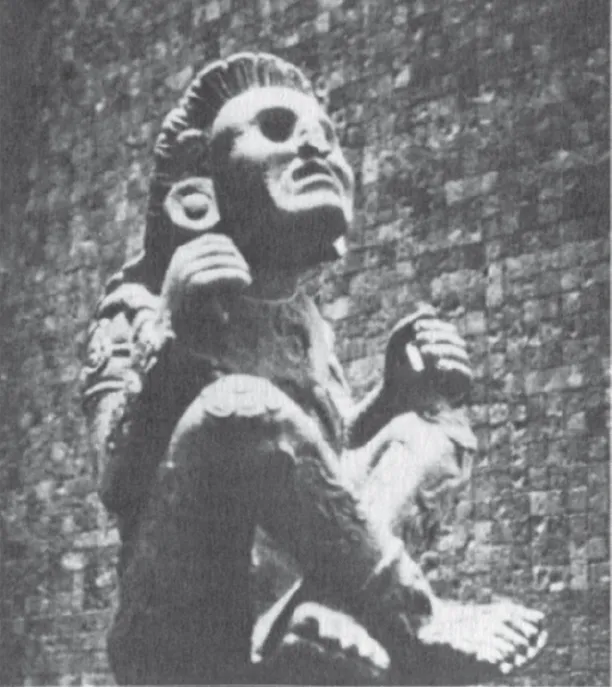

Statue of Xochipilli, the prince of flowers and god of abundant food, pleasure and love.

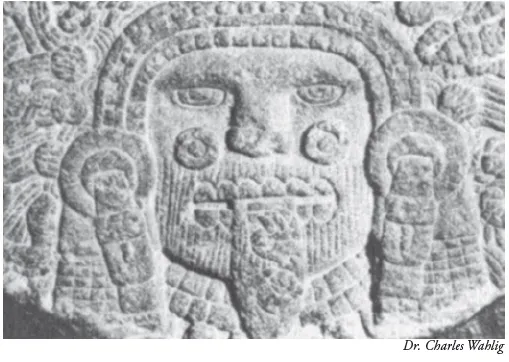

Close-up of the colossal monolithic statue of Coatlicue, a monstrous woman, with jaguar’s paws and eagle’s claws for feet.

Detail of the famous monolithic Aztec calendar (a huge stone disc) showing Tonatiuh, the sun, whose movement is only maintained by human sacrifices. He puts out his tongue, athirst for blood.

An artist’s depiction of Aztec ritual sacrifice. The victim was laid across a stone and his heart gouged out. The process took only a few seconds. As many as 20,000 victims would be sacrificed at the dedication of a temple.

At that time, Tenochtitlan was surrounded by large lakes and approached by three causeways. One of the Spaniards, Diaz del Castillo, has left us a graphic account of the invaders’ first view of Montezuma’s fabled capital. “Gazing on such wonderful sights, we did not know whether that which appeared before us was real, for on one side in the land there were great cities and in the lake many more, and the lake itself was crowded with canoes, and on the causeway were many bridges at intervals, and in front of us stood the great city of Mexico and we Spaniards … did not number 400 soldiers.”2

The edges of the island city were fringed with verdure and crowded with white houses and their patio gardens. The metropolis itself was threaded with canals crossed by bridges, somewhat like Venice today, while streets and open squares were few in number. Here and there, great temples thrust skywards like truncated pyramids, and gilded palaces and stately public buildings rose proudly amid teeming markets, zoos, aviaries and gardens of colorful flowers. The Spaniards were full of wonder and respect for the gleaming outward appearances of this pinnacle of Aztec civilization.

On November 8, 1519, in a ceremony of glittering spl...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Author’s Preface

- 1. The Conquest of Mexico

- 2. The Visions at Tepeyac

- 3. The Conversion of the Aztecs

- 4. The Historical Basis of Guadalupe

- 5. The Development of the Cultus

- 6. The Modern Era

- 7. The Verdict of Science

- A Chronological Summary of Events

- Bibliography