![]()

CHAPTER 1

I and My House Will Serve the Lord

In 1844, Count Matthias von Galen erected a new chapel on the family property at Castle Dinklage. The chapel, large enough to be a small village’s parish church, had an inscription above the side entrance:

I AND MY HOUSE WILL SERVE THE LORD. JOS[HUA] XXIV, 15

MATHIAS VON GALEN AND ANNA VON KETTELER THE LADY OF HIS HOUSE BUILT THIS HOUSE OF GOD AND CELEBRATED ITS DEDICATION ON THE DAY OF ITS PATRON ST AUGUSTINE, 28 AUG. 1844

For Matthias and Anna von Galen, as members of old noble houses, it was self-evident that they should serve the Lord, live the life of the Catholic Church with deep piety and love, and conscientiously fulfill their obligations to Church and country. They were to pass these principles on to their children and grandchildren and beyond.

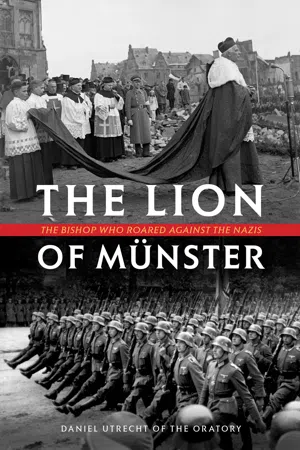

Anna was the sister of Wilhelm Emmanuel von Ketteler, the Bishop of Mainz from 1850 to 1877, who was a pioneer of Catholic social teaching and a great influence on Pope Leo XIII’s encyclical Rerum Novarum (1879). The second, fifth, and eleventh of Matthias and Anna’s thirteen children became priests, and among their grandchildren are two who have been honored by the Church with the title Blessed. Maria Droste zu Vischering (1863–1899), in Religion Sister Maria of the Divine Heart, was superior of the Sisters of the Good Shepherd in Porto, Portugal. She strove for the rehabilitation of girls and young women driven into prostitution by poverty and urged Pope Leo XIII to consecrate the world to the Sacred Heart of Jesus, which he did two days after her death. Her younger cousin, Clemens August von Galen, the subject of this book, was chosen Bishop of Münster soon after the National Socialist German Workers’ Party of Adolf Hitler took power in Germany in 1933. The “Lion of Münster,” as he came to be called because of his courage in speaking out against Nazi injustices, outlived the Nazi regime by less than a year.

The fourth child of Matthias and Anna, Ferdinand Heribert von Galen, born in 1831, was to inherit his father’s position as head of the family and hereditary chamberlain because his oldest brother, the second child, became a priest and the next son died as an infant. In 1861, Ferdinand Heribert married Imperial Countess Elisabeth von Spee. She also came from a staunchly Catholic noble family. Three of her half brothers became priests, and two of her half sisters became Dominican nuns. Ferdinand and Elisabeth also had thirteen children, of whom Clemens August was the eleventh.

Life at Burg Dinklage, in Lower Saxony (northwestern Germany), was full of love and joy and at the same time was strict and austere. The castle is not what we might think of as a castle. It could hold out against half a dozen knights on horseback in the Middle Ages, but it was really a large set of timber-and-brick farmhouses and barns surrounding a central courtyard, encircled by a moat. There was no running water and, in most of the rooms, no heat. On the ground floor of the left wing were stalls for horses. The children’s rooms were above. As Clemens August grew to his full height of over six and a half feet, he not infrequently bumped his head on the ceiling beams of these rooms. An open gallery faced the interior courtyard. The windows on the opposite side looked over the moat to the chapel, to the house of the forester, and to the fields and woods where the children learned to hike, ride, and hunt.

Each day began with Mass at the chapel—a short walk from the front gate, over the moat, to the right, and to the right again. Punctuality was expected. If one of the sons was late for his service as an altar boy, he would get no butter for his bread at breakfast. Those who missed Mass altogether could expect no breakfast at all. Clemens, in later life, remembered a morning when he and his closest brother Franz overslept. “Strick,” he cried, addressing Franz by his family nickname, “hurry, we’re late for Mass.” “Well then, Clau,” replied his sleepy brother, using the nickname for Clemens August, “we may as well keep sleeping, because we’re not going to get breakfast anyway!” In the evenings, the father led the Rosary in the chapel for the family and servants, followed by a meditation lasting half an hour.

Life in Castle Dinklage gave the von Galen children a love for their family; a sense of what it meant to be an aristocrat related to many of the noble houses of Europe; a keen awareness of the social responsibility that was expected of members of an old noble house; a love of their German fatherland; and a love for the people, landscape, customs, and dialect of the Heimat. The Heimat was the home territory, the particular part of Germany in which Dinklage was situated, known as Oldenburger Münsterland. In the complex history of the patchwork of kingdoms, principalities, duchies, counties, and cities that came to be modern Germany, the region of Vechta, which included Dinklage, ended up politically as part of Oldenburg in Lower Saxony, but ecclesiastically it remained part of the Diocese of Münster in Westphalia. To this day, the Oldenburger part of the Münster Diocese is divided from the rest of the diocese by part of the Diocese of Osnabrück.

Above everything else, family life at Dinklage gave the von Galen children a love for the Catholic Church. Ferdinand Heribert and Elisabeth took great pains in the religious education of their children. The farmers and craftsmen of the village of Dinklage, as well as the family and servants at the castle, lived and loved their religion. Münster and Oldenburger Münsterland were staunchly Catholic areas. At roadsides and entrances to farms and businesses, on paths in the woods, one still sees countless shrines: images of the crucified Lord, the Blessed Virgin, and the sorrowful Mother holding her dead son and shrines displaying a prayer for the family or an expression of trust in the Lord’s love and mercy. When Clemens August was at boarding school, later in the seminary, and still later as a priest serving in Berlin, his letters to his family constantly returned to the thought of the feasts they celebrated in the chapel built by his grandfather or the outdoor procession of the Blessed Sacrament on Corpus Christi. He sent greetings not only for birthdays but for name days and family anniversaries, and he always recalled with thanksgiving to God—and to his parents for passing on the gift of the Faith—the anniversaries of his own Baptism and first Holy Communion.

Family tradition and Catholic tradition were firmly bound together. In the long history of the Münster Diocese, a von Galen had been bishop before: Christoph Bernhard von Galen ruled the diocese from 1650 to 1678. In those days, when the bishop was also the secular ruler as prince-bishop, Christoph Bernhard was known for the quality of his army, especially his artillery, which won him the nicknames “Bomben Bernd” and “the Cannon Bishop.” But he was also a deeply religious man and a good bishop. The ambulatory chapels that he added to the Cathedral of St. Paul in Münster became the place of his tomb and also that of his twentieth-century relative.

The nineteenth century brought a separation between civil and Church authority and frequent struggles over what influence the Church should have on civil and public life. When Clemens August was born in 1878, the Kulturkampf—culture war—waged by German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck was beginning to wind down. As the architect of the new German empire dominated by heavily Protestant Prussia, Bismarck had sought to reduce the influence of Catholicism on public life. Religious houses were closed, and priests who criticized the government from the pulpit were imprisoned. This persecution only succeeded in deepening the Catholic identity of Münster, a place with a strong Catholic history in what was a largely Protestant part of Germany. All Catholics of Münster honored their “Confessor Bishop,” Johann Bernhard Brinkmann, who was imprisoned for forty days by the Prussian government in 1875. He spent the years 1876 to 1884 in exile in Holland after the government declared him deposed, only to return in triumph to finish his life as Bishop of Münster. Clemens August was proud of the fact that his father twice secretly visited Bishop Brinkmann in Holland and had previously visited him during his imprisonment in Warendorf.1 In an earlier generation, Clemens August Droste zu Vischering, the Archbishop of Cologne, spent some time in prison in 1837 for refusing to allow priests to celebrate mixed marriages between Catholics and Protestants unless there was a guarantee that the children would be raised Catholic. At that time, Wilhelm Emmanuel von Ketteler, who would later become bishop, resigned his position in the civil service, refusing to serve a state that would require the sacrifice of his conscience.2

Clemens August von Galen grew up when these events were still a part of everyday life. Political discussion on the role of the Faith in the state, and the obligations of conscience of a citizen, was regular fare at Castle Dinklage. Count Ferdinand Heribert took an active part in the Centre Party and the Catholic political party and was a member of the Reichstag in Berlin for thirty years. All this contributed to Clemens August’s outlook on life. “Father took life and his duties and responsibilities very seriously,” he wrote years later in a family history that he produced for his young nephew when the latter became head of the family:

He had a unique gift, and the regular practice, of considering all questions on the basis of principles, and seeking their solution from the fundamentals of the knowledge of natural and supernatural truth. He considered himself obliged to train us from our youth to think in this fundamental way. To strengthen this in us, he wanted his sons after secondary school to get a fundamental education in Christian philosophy. Through earnest private study, he was constantly working on improving his mind, so that it would serve him with strong logical thought and clear, certain decision. All of us were constantly learning from him. He let us take part in his studies: every morning after breakfast he read to Mother and the older children from a serious book, frequently a historical one. In my years we had Janssen’s History of the German peoples, Brück’s History of the Catholic Church in Germany, the biography of Fr Pfülf, S.J., Pastor’s History of the Popes, as many volumes as had appeared by that time; also journals such as the “Historical-Political Paper” and “Voices from Maria-Laach.” From this, in addition to the daily occurrences in the Church and the world, in the house and in the family, there was a great wealth of material for earnest discussion in the family circle. Mother followed these discussions with great interest, but also took care that we were not lacking in beautiful literature: in the evening after prayers Father would read in the family circle the works of Catholic poets and novelists. In the Catholic newspapers—there were never any other papers in Dinklage—politics was followed assiduously.3

Elisabeth von Galen taught all her children their Catechism and gave them such a thorough and good foundation that Clemens later realized that he never learned anything new about the Faith until he began the study of theology. Personal service to the poor was practiced by both parents. The mother and daughters made clothes by hand for poor families and rosaries for the children of the village to receive when they made their First Communion.4

The inscription over the entrance of the chapel came from the Book of Joshua. Joshua had challenged the Israelites after their entry into the Promised Land to decide whom they would serve, the pagan gods of their ancestors or the pagan gods of the peoples now living around them. As for him and his house, they would serve the Lord: This motto perfectly expressed the essence of life at Castle Dinklage. When as Bishop of Münster, Clemens August was in constant struggle for the rights of the Church against Nazi totalitarianism, he once told a Jesuit priest, “We Galens aren’t great-looking, and maybe we’re not very smart; but we’re Catholic to the marrow.”5 Among relatives, he used the same line but gave it a more pungent conclusion: “We aren’t great-looking and not very smart, but we’re brutally Catholic [aber wir sind brutal katholisch].”6

Clemens August Joseph Emanuel Pius Antonius Hubertus Maria Count von Galen was born in Castle Dinklage on March 16, 1878, and baptized three days later in the temporary church that was serving the village while a new parish church was under construction. The long list of names he was given reflects a common practice among the nobility and was one more element that kept tradition in memory. The double name Clemens August began to be used among the nobility in the eighteenth century to honor Duke Clemens August von Bayern. This man was named Bishop of Regensburg in 1716 at the age of fifteen, resigned that post at eighteen, and managed to acquire and hold simultaneously the posts of Archbishop of Cologne and Bishop of Münster, Paderborn, Osnabrück, and Hildesheim from different dates beginning in 1719 until his death in 1761. In his younger days, Clemens August von Galen used only the single name Clemens but took the double name when he became a bishop, perhaps thinking not only of Clemens August von Bayern but also of Clemens August Droste zu Vischering, the bishop who was imprisoned in 1837 for his courage in defending the Catholic faith. Clemens von Galen was baptized on the feast of St. Joseph. That—and the fact that an older brother named Joseph had died two years earlier at the age of two and a half on March 16, the date on which Clemens was born—accounts for the name Joseph. The name Emanuel recalled Bishop Wilhelm Em[m]anuel von Ketteler, who had died the previous year, in 1877. Pope Pius IX, whom Count Ferdinand Heribert had served as honorary chamberlain during the (First) Vatican Council, had also recently died in Februar...