This is a test

- 115 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Canticle of Brother Sun

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Cosmic ode, poetic masterpiece, spiritual summit, prayer for peace, call to fraternity: the Canticle of Brother Sun is known by all, or at least its title is, and it has been celebrated in many ways, set to music so many times. Yet, there is something in it that resists, which is why it will never completely be a classic. It continues to vibrate with its initial transgression which pushes it towards the universal while remaining in the assumed particularism of a vernacular dialect. The call to peace is also a coup de force and its profession of fraternity rises from an infinite solitude of suffering. The Canticle is primarily a cry. Let us listen to it with "the ear of our heart."

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Canticle of Brother Sun by Jacques Dalarun, Philippe Yates in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Christian Denominations. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Theology & ReligionSubtopic

Christian DenominationsTHIRD ACT

On the strength of the Assisi Compilation, it is usually accepted that the last verses of the Canticle of Brother Sun, more precisely those on forgiveness and death, were added to a text that was already complete. Here is the account of the first addition:

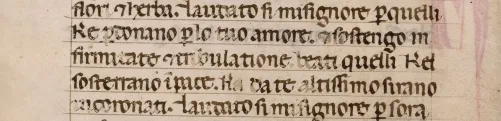

At that same time when he lay sick, the bishop of the city of Assisi at the time excommunicated the podestà. In return, the man who was then podestà was enraged, and had this proclamation announced loud and clear, throughout the city of Assisi: no one was to sell or buy anything from the bishop, or to draw up any legal document with him. And so they thoroughly hated each other. Although very ill, blessed Francis was moved by pity for them, especially since there was no one, religious or secular, who was intervening for peace and harmony between them. He said to his companions: “It is a great shame for us1, servants of God, that the bishop and the podestà hate one another in this way, and that there is no one intervening for peace and harmony between them.” And so, for that reason, he composed one verse for the Praises:Laudato si’, mi’ Signore, per quelli ke perdonano per lo Tuo amoree sostengo infirmitate e tribulatione.Beati quelli ke ‘l sosterrano in pace,ka da Te, Altissimo, sirano incoronati2Praised be You, my Lord, through those who give pardon forYour loveand bear infirmity and tribulation.Blessed are those who endure in peacefor by You, Most High, shall they be crowned.

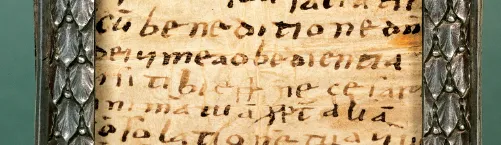

[XLII. Francis of Assisi, Canticle of Brother Sun. Assisi, Biblioteca comunale, ms. 338, f. 33v. The verse on forgiveness.]

Francis afterwards asks his companions to gather the bishop, the podestà – the principal magistrate of the commune, elected for a brief period – and all the citizens in the square in front of the bishop’s palace. One of the brothers declares to them:

In his illness, blessed Francis wrote the Praises of the Lord for His creatures, for His praiseand the edification of his neighbor. He asks you, then, to listen to them with great devotion.

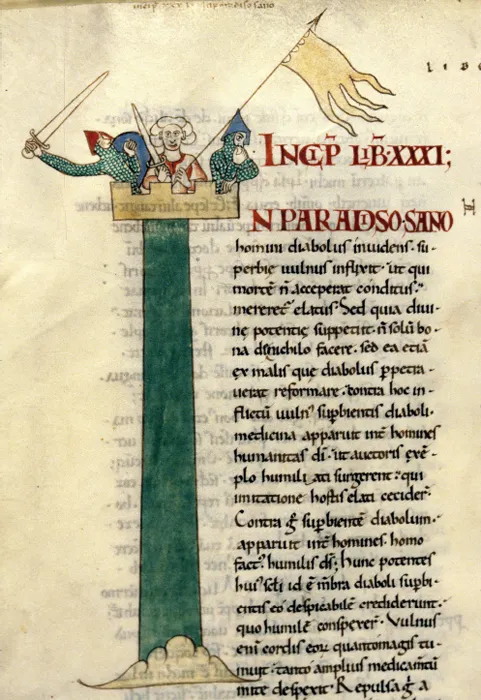

The song is intoned. The podestà, moved to tears “as if it were the Gospel of the Lord”, is the first to pardon the bishop and to throw himself at his feet. The bishop lifts him up, confesses his tendencies to anger and they embrace3. One has a sense that the narrator’s heart inclines towards the communal magistrate – probably Oportulo, son of Bernard, who was one of Clare’s active supporters4 - more than to bishop Guido II, with whom Francis had strained relations5. But all that matters is the happy outcome. And for all to recognize the merits of the saint in this sudden reconciliation. In 13th century Italy, everything was fuel for conflict: the rivalry between pope and emperor frequently turned into armed conflict; neighboring cities made war on each other; within each city, the bishop and the commune were frequently opposed; within communes nobles and the minores tore into each other; vendettas between enemy families were never ending, in this urban landscape bristling with castellated towers, thrown towards the sky like so many challenges.

[XLIII. Fortified tower and its defenders. Dijon, Bibliothèque municipale, ms. 173, f. 133v, first third of the 12th century, Cîteaux. Gregory the Great, Moralia in Job]

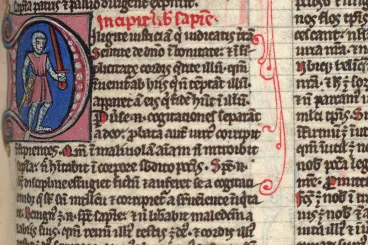

Francis, the son of a merchant, counted himself among the party of the minores, the better off among the non-nobles. But he aspired to chivalric glory. At night he dreamed of it.

For it seemed to him that his whole house was filled with soldiers’ arms: saddles, shields, spears and other equipment. Though delighting for the most part, he silently wondered to himself about its meaning. For he was not accustomed to see such things in his house, but rather stacks of cloth to be sold.6

A knight in fact, since he could not be a knight by title, Francis took part in the battle of Collestrada where, in 1202, the minores of Assisi were defeated by the city nobles, allied with rival Perugia. He was taken prisoner there7. Equipped from head to foot, flanked by an equerry, he prepared to leave for Puglia in 1205 to join the pope’s armies fighting against those of the emperor and to have himself knighted by a count. It took a voice, heard while he was half-asleep, to dissuade him:

[XLIV. Knight holding a sword. Paris, Bibliothèque Mazarine, ms. 24, f. 199r, c. 1230-1240, Paris. Bible.]

[XLV. Knight. Besançon, Bibliothèque municipale, ms. 434, f. 257r, 1372, Paris. James of Cessoles, Moralized Game of Chess, translated by John of Vignay.]

“Who can do more for you, the lord or the servant?” “The lord,” he answered. “Then why are you abandoning the lord for the servant, and the patron for the client?” To which Francis responded: “Lord, what do you want me to do?” “Go back,” it said, “to your own land to do what the Lord will tell you.”8

In medieval society, the greatest distinction – that chivalry dreamt of by the merchant’s son, embarrassed by his bails of cloth – was founded on physical force, the art of killing, or at least of flooring one’s opponent. The dominant ones were the warriors, and they were proud of being such. Francis’ conversion was a complete reversal of chivalric values, the discovery of the only true lordship of the Most-High.

From then on he held peace to be the supreme blessing. Echoing Luke’s Gospel9, he encouraged his brothers to greet those from whom they sought hospitality with the words “Peace to this house”10. He sent a letter “to all the podestàs and consuls, magistrates and governors” advising them to do penance11. From January to November 1233, the Friars Minor of northern Italy intervened more directly in civic life through the “great devotion” movement, an ardent preaching campaign to end the cities’ internal conflicts which is also known by the beautiful name of the “Alleluia” movement12.

By this logic, Francis, hurt and ashamed that no one was intervening to resolve the conflict between the bishop and the podestà – in particular “no religious” whose role it should have been – is supposed to have added the verse on forgiveness to the Praises of the Lord that he had “already composed”. All seems to flow together, and yet, this account is not entirely convincing.

The Assisi Compilation clarifies that the addition took place “at the same time” as the composition of the poem. The best estimates date the conflict between the bishop and the podestà to May 1225, during the same springtime that Francis lay sick at San Damiano and dictated the Canticle of Brother Sun. From this, the hiatus between the estimated dates of the two compositions either disappears or becomes very short. Franciscan legends show time and again that the Assisi penitent also practised “repentir”, in the sense that painters use the word. Often he recalls a brother on the point of departure in order to complete, modify or even countermand the message that he had originally given him. The most striking case of such writing in fits and starts is the handwritten Note to Brother Leo, the last four lines of which Attilio Bartoli Langeli showed masterfully were a later insertion, as to their writing, and a revision, as to their content. An addition, certainly, but an indispensable one for the general meaning of the message: do not come to see me if you want to know what you have to do as a member of the community, but come to see me if your soul is in need of comfort13.

[XLVI. Francis of Assisi, Handwritten Note to Leo. Spoleto, Cathedral. The ink of the four last lines is paler, the hand more hesitant, the lines less regular.]

It is cle...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Abbreviations

- Transgressions

- The Canticle of Brother Sun

- Francis As Author

- The Canticle Tradition

- The Genesis of The Canticle

- First Act

- Second Act

- Third Act

- Reconcilliation

- Harmony

- Franciscan Chronology