![]()

PART I.

THE USUAL GANG

![]()

1. Inside the Editorial Process:

Mad Veterans Jaffee and Meglin Look at Their Editors

Paul Levitz

A RECURRING DISCOURSE between the scholarly community and the people who create fiction in any medium involves the interpretations of the work and search for creative intent. It’s frequently true that scholars find meaning and intent that the creators were unconscious of placing in the work, or even deny is a fair reading of their work. Mad magazine was inarguably a significant force in shaping American popular culture in its decades as the country’s best-selling humor magazine (circulation exceeded 1.5 million from 1965 to 1979). Its satirical looks at our behavior, institutions, media, and advertising influenced its readers and generations of creative people working in other forms. Given Mad’s popularity, it is useful to examine questions of intent, as well as the shared cultural influences that shaped its editorial staff and extremely loyal contributors (“The Usual Gang of Idiots”). Without any claim to objectivity, after serving for seventeen years as the magazine’s second publisher, I instead offer for consideration primary resources in the form of lengthy interviews with two of the longest-serving and most articulate participants in Mad’s creation.

Al Jaffee first appeared in Mad in 1955 and continued into 2019 to contribute his distinctive fold-in to every issue. Nick Meglin joined Mad’s editorial staff in 1956 and retired in 2004 after serving as the co-editor for the last twenty years. They worked with all of Mad’s editors: Harvey Kurtzman (1952–1956), Al Feldstein (1956–1984), Nick Meglin and John Ficarra jointly as co-editors (1984–2004) and John Ficarra individually (2004–present). For your consideration, then, our 2014 conversations, which may fuel further discourse.

The following interview with Al Jaffee was conducted February 20, 2014.

Paul Levitz: Al, I believe you’re the only living writer who has worked closely with all four of the men who edited Mad magazine: Harvey Kurtzman, both at Mad and his later projects, Al Feldstein, Nick Meglin, and John Ficarra. I’d like to explore with you the differences among the four men’s worldviews and processes, and how that affected the material in the magazine.

Al Jaffee: Well, Harvey was a huge influence, and Harvey’s Mad magazine was unique, but Harvey was influenced by other publications. Crazy stuff that came out here and there. But Harvey’s thinking process was just so special. He knew each person that worked with him, what very special talent that person had. He ignored all the surrounding chaff. He didn’t care that I knew nothing about anatomy; what he liked was how I saw the world, and the same about Will Elder or Jack Davis or Wally Wood. He went after that one little spark that made that person unique and outstanding as a talent. Will Elder couldn’t write a story if he stood on his head, but he could interpret a Harvey Kurtzman story in a way that even Harvey never dreamt he could. And Harvey supplied Willie with very stick-figure storyboards, but then Willie would take hold of them and put a whole new world of life into it.

I remember when Harvey came after me. Mad was going to become a magazine, switching from a comic book. He said to me, “I’ve had my eye on you.” I said, “When? Where?” “Oh, when we were in Music & Art together1—I was a freshman and you were a senior—I investigated you; I knew all about you. I’d like you to come work for Mad.”

I said, “I’ve seen Mad [the comic book],2 and my work in Patsy Walker is about a teenage girl—what’s that got to do with Mad?” “Oh, I know what you can do . . . I just know.” I remember saying, at one point, “Willie and I were friends as teenagers, and we had a contest about who could make up the funniest things. Do you want me to be like Willie?” Harvey said, “No, I don’t. I want Jaffee.” “Well, where is Jaffee? What do you see in Jaffee?” He said, “I know what I’ve seen, and I’ll get it out of you.”

Eventually I ended up following Harvey to Trump and Humbug,3 and ended up being accepted in Harvey’s creation, Mad, even though he wasn’t there anymore.

P. L.: Let me go back a bit. Editors bring a lot to what they do, if they’re good editors, and Mad has been blessed with some wonderfully skilled and talented people doing it. But an editor also brings, to some measure, a worldview, politics, sociology, and his or her life. One of the things that is fascinating about Mad is the degree to which Mad affected the culture, and didn’t just mirror the culture, for a long time. I really believe that Mad is one of the things that made the ’60s possible, and even made the Watergate-era cynicism possible in many ways.

A. J.: Yes.

P. L.: I’d love to trace with you what the worldview of each of these guys was, and how it affected the dynamic of working with each of them, the kind of stories they asked you to do, the kind of humor they were interested in, whether there was a challenge from one to the other. Certainly, they saw themselves as different kinds of people, with different kinds of roles. Al is the one I know least well; we’ve shaken hands once or twice over the years, but never had a real conversation. Harvey I knew a little bit when he was still well. Nick and John very well, of course, from many years of working with them. Let’s start with Harvey. Did Harvey have a consciousness that he was shaping the world, that he was influencing people with what he put in his magazines?

A. J.: I don’t think Harvey had visions of grandeur, or breaking new ground or anything like that. I think Harvey had a vision of what he thought would be a funny thing to do. I remember Harvey telling me that when he was a little kid, maybe six years old or so, he made up magazines and distributed them in the neighborhood, just folding paper up and stapling it, putting drawings on each page. He told me once that he dreamed of someday having a magazine and being able to gather in people like me and Willie, and doing special things. We can all say things like that—we all have dreams of glory and stuff like that. But Harvey was a very deep thinker. He had difficulty in front of an audience, making a speech. He even had difficulty relating to talent at times, because his mind was racing, in my view, with so many creative notions going on at the same time that he couldn’t convey it. So, he went looking for people that he felt could think his way.

The first thing he said to me was, “Write something for me.” I said, “I’m looking on you as an editor—give me an assignment. What am I going to do, write about my children, or what?” “Just write a funny Al Jaffee thing.” “Do I have to draw it?” “No, I have enough artists.” So, at that time, at the time it was the early days of television, and you watched anything that moved—one of the things that was on was boxing. So I wrote a boxing story and brought it to Harvey, and he gave it to Jack Davis and of course Harvey married the two things together. Jack Davis did a magnificent job, showing boxing for what it really was. I saw boxing for what I thought it was—a violent, bloody sport. We weren’t trying to knock boxing, but we wanted to show an aspect that was ignored by the general public, which is that it’s basically very violent. Later on, I wrote something similar about football, and Jack also did that.

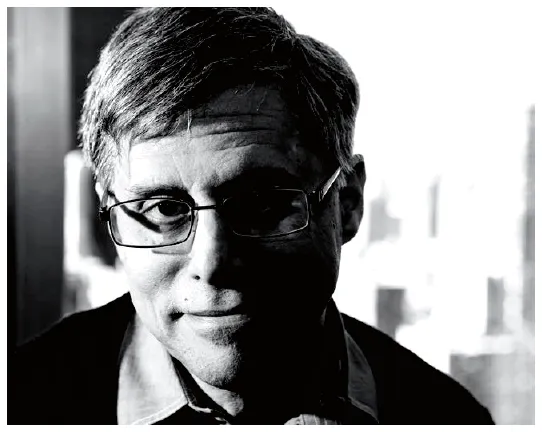

Fig. 1-1: Paul Levitz. Photo courtesy of Paul Levitz.

What Harvey saw in me was a writer, and, I think, Al Feldstein also hired me as a writer, which I was for a year and a half at Mad because this new medium of poking fun at the underbelly of our institutions was becoming so popular—satire, parody, so on—was so new that even though people like Sid Caesar were doing it on television, there just wasn’t enough of it. There were tough times with one war ending, then another starting in Korea, and then another in Vietnam, so there was a hunger for lighter stuff, and there weren’t a lot of magazines around doing that. The only light stuff was syndicated comics, and some of the kiddie comics with rabbits and pigs and the like.

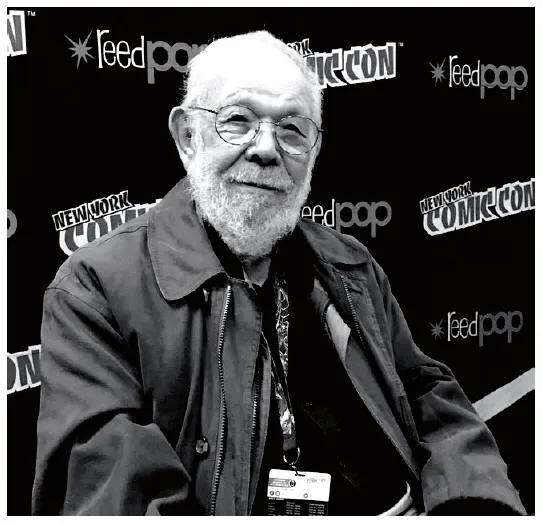

Fig. 1-2: Cartoonist Al Jaffee following a discussion panel dedicated to Trump magazine on Sunday, October 9, 2016, at the Jacob K. Javits Convention Center in Manhattan, Day 4 of the 2016 New York Comic Con. © Luigi Novi / Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:10.9.16AlJaffeeByLuigiNovi2.webp.

P. L.: That was harmless stuff, devoid of any real . . .

A. J.: Yes. There was no humorous stuff commenting on the things affecting our daily lives: advertising, politics, false advertising . . . the chicanery of unscrupulous businesspeople and bankers with phony mortgages and loans.

The early Mad [under] Harvey Kurtzman wasn’t a crusader. The humorous aspect of the satire was really the focus. I remember he did something very funny in the comic version of Mad, which was about going to a Chinese restaurant, which Will Elder illustrated. It was a chaotic scene in a Chinese restaurant, with all of Will Elder’s funny little flourishes. An exaggerated view of a Chinese restaurant from the point of view of people who had never been to a Chinese restaurant. It wasn’t making fun of Chinese restaurants, but making fun of the ignorance of the average person going into a place he didn’t know much about. Mostly it was for fun. And then, of course, Harvey in the comic book version of Mad made fun of other comics: “Superduperman!” and so on.

P. L.: He took the Tijuana Bible [genre of small-format pornographic comic books], cleaned it up, and pointed out the outrageousness of the basic premises of some of the comics.

A. J.: In retrospect now it looks like such a natural, easy thing to do. But when there’s nothing around like that, trying to get it printed . . . . It was easy for Harvey and Willie and me to sit around and regale each other with funny ideas, but then you have to go to a Martin Goodman or a William Gaines and say, “Will you print this?”4 Getting something like Mad going . . . .

I don’t know that story too well. Harvey worked for Bill Gaines at EC, as did Al Feldstein. Al was a very prolific writer of the horror stuff; a very good writer and he could knock the stuff out over and over again. Harvey, on the other hand, did war stories and did tons of research to make sure that he had all the details of the military campaign and all that. The balance of income, since comics was always based on piece-work, [was unbalanced]; Feldstein was making a fortune, and Harvey was starving to death. Harvey was so slow, and if he needed research, he’d take a trip and spend the whole day interviewing people. Harvey complained about his lack of income, and Bill, as the story goes, said, “Create a funny magazine and I’ll let you do that and you can make more money since you won’t have to do the research.”

P. L.: Did Harvey have any pronounced politics beyond the typical New York Jewish, left-leaning mishugas that so many of us shared automatically?

A. J.: I would have to say that Harvey was quite conservative. He had a conservative moral attitude. As a matter of fact, he took us to a Playboy Club once because of his friendship with Hefner, and one of us made some kind of leering, sexist observation, and Harvey was appalled. He was very straitlaced. In fact, when Hefner invited us to his mansion in Chicago to work on the early phases of Little Annie Fanny (I was only there along with Arnold Roth and Russ Heath to get this going, as Hefner was impatient with how slow Harvey and Willie were) . . . while we were living in the mansion, there were also floors of bunnies living in the mansion. The girls were curious; they’d come up to see what kind of artwork we were doing. Just teenage girls who dressed up as bunnies when they went to the club. Harvey became like a Mother Superior. You could almost hear him saying, “Look, but don’t touch!” He was so fearful that one of us would get out of hand. We made fun of Harvey, and he red-facedly admitted he was old-fashioned. Harvey was not a wild, crazy guy . . . he was a very serious humorist. He didn’t have an axe to grind. He looked at everything from a very conservative and moralistic point of view, which is that if you’re going to make fun, even of a product, be fair. He created advertising like “Canadian Clubbed” based on the whiskey ad. His main focus was to pull away the curtain that the advertisement implied—good taste, pleasant company, fun, and all of that—and he would push it towards drunkenness. That’s what we’re really selling.

And this was a difference between Harvey and Al Feldstein: Feldstein would use expressions like “Let’s hit them hard.” Harvey felt, “Do it softly. Expose, imply, but don’t editorialize.” I liked Harvey’s approach; I never had any problems working with Al Feldstein either, but that’s my personality. I’m a journeyman cartoonist, and the editor’s in charge. What the editor wants I have to give him.

P. L.: Tell me about what Feldstein wanted. He comes into Mad, and the tone shifts when he arrives fairly quickly. Partly, it feels more structured than Harvey’s. You have a flexible feeling with Harvey (partially because it was just the first couple of magazine issues, and he was finding his way). Feldstein fairly quickly says we’re going to have departments, we’re going to have this parody here, this parody there. We’re going to break it up with these three things—a Don Martin kind of single page each third of the way through the magazine so you can have a simple laugh...