eBook - ePub

Reflections of Alan Turing

A Relative Story

Dermot Turing

This is a test

Share book

- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Reflections of Alan Turing

A Relative Story

Dermot Turing

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Everyone knows the story of the codebreaker and computer science pioneer Alan Turing.

Except …

When Dermot Turing is asked about his famous uncle, people want to know more than the bullet points of his life. They want to know everything – was Alan Turing actually a codebreaker? What did he make of artificial intelligence? What is the significance of Alan Turing's trial, his suicide, the Royal Pardon, the £50 note and the film The Imitation Game?

In Reflections of Alan Turing, Dermot strips off the layers to uncover the real story. It's time to discover a fresh legacy of Alan Turing for the twenty-first century.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Reflections of Alan Turing an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Reflections of Alan Turing by Dermot Turing in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Tecnología e ingeniería & Biografías de ciencia y tecnología. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

ROBOT

Alan Turing’s design for a programmable computing machine which was going to meet all Britain’s computational needs was done almost as soon as he reported for work at the National Physical Laboratory in 1945. As with World War Two, the question now was what he was actually going to do with his time while everyone waited for the machine to be built. Since there was no war on, and the country was in a lengthening period of post-war austerity, that proved to be a very long time indeed:1

1 October 1945: Alan Turing arrives at the NPL.

13 February 1946: a summary of Alan Turing’s design report for the Proposed Electronic Calculator (later named ACE, or the Automatic Computing Engine) is delivered up for approval by the Executive Committee of the NPL; project approved.

23 July 1947: no machine yet; Alan Turing takes a sabbatical away from the NPL.

28 May 1948: no machine yet; Alan Turing leaves the NPL.

29 November 1950: first demonstration of the ACE Pilot Model (a small-scale proof-of-concept model).

7 June 1954: Alan Turing dies.

Late 1958: commissioning of the full-scale ACE.

There was, during 1946, very little to do, apart from write programs for a machine that did not yet exist, and to speculate on what it might do once it was up and running. The hierarchy of the NPL, part of the Department of Scientific and Industrial Research, certainly did not much like its scientific officers speculating to the press about machines and creating a sensation. Things like this:

BRITAIN TO MAKE A RADIO BRAIN

‘Ace’ Superior to U.S. Model

BIGGER MEMORY STORE

Britain is to make a radio ‘brain’ which will be called ‘Ace’ at a cost of between £100,000 and £125,000, it was announced by the Department of Scientific and Industrial Research last night. Only one will probably be made …

THREE YEARS TO BUILD

It will be able to cope by itself with all the abstruse problems for which it is designed. Further advances will probably enable production of machines designed to do even more than Ace. It will take two or three years to build. Leading the team working on the ‘brain’ are Sir Charles Darwin, Director of the laboratory; Dr A.M. Turing, who is 34 years old and conceived the idea of Ace …2

This particular report was put into the press late in 1946 by Lord Mountbatten, rather than Alan Turing, but the result was the same. There was to be no more press coverage. To generate a frenzy of expectation, when the department was building the machine very gradually, was bad enough, but a much bigger danger was that the imagination of Alan Turing was completely out of control. On 20 February 1947, Alan presented the concept of the ACE to the London Mathematical Society.3 Basic computing concepts were laid out: things like memory, binary arithmetic, programming and so forth. What came later in the talk probably got lost in the generally theoretical and forward-looking prospectus: the capabilities of a machine which was going to take a lot more than three years to build. In this talk, Alan Turing described things which must have seemed wholly fantastic:

Since the machines will be doing more and more mathematics themselves, the centre of gravity of the human interest will be driven further and further into philosophical questions of what can in principle be done etc. … It has been said that computing machines can only carry out the processes that they are instructed to do … Up till the present machines have only been used in this way. But is it necessary that they should always be used in such a manner?

He goes on to suggest that the machine’s program might be changed by the machine itself, that the changes might improve the process and the results, and at that point the machine:

would be like a pupil who had learnt much from his master, but had added much more by his own work. When this happens I feel that one is obliged to regard the machine as showing intelligence.

When the machine got on with the maths, the humans would start to test the capabilities of the machine; the great calculator could become an exotic and slightly dangerous performing elephant in a mathematical circus. To the relief of Sir Charles Darwin, in 1947 no one seemed to be listening to Dr A.M. Turing.

Alan Turing went back to the NPL and twiddled his thumbs for another few months. By July, Darwin suggested that Alan might take a year’s sabbatical while the machine got itself built, and focus on more ‘theoretical’ aspects of computing machinery.4 This was, when decoded, a way of caging the elephant.

The report Alan wrote during his sabbatical year5 didn’t go down too well. The paper describes not only ‘logical computing machines’ – the theoretical sort of thing described in ‘On Computable Numbers’ – but, moving on to and then beyond ‘practical computing machines’ like the ACE, it speculates about ‘unorganised machines’. The last of these were wild elephants which had no place in a serious computing laboratory. A reader in 1948, knowing that computing machines were for maths, wholly for maths, and nothing but maths – the ACE was the creature of the Mathematics Division of the NPL – would surely have agreed, seeing as how anything ‘unorganised’ was not at all in keeping with the straight and narrow path of the calculation of sums. The heading of the section on unorganised machines was unfortunate, since the content is practical and to the point. The machines were only ‘unorganised’ because they were designs for machine-learning prototypes or machines whose program was not fully preordained – not exactly what we use today in machine-learning procedures, but something which worked. There were circuit schematics and worked examples. The idea that a machine might respond to the ‘teaching’ stimulus it received, and correct or modify its programmed behaviour, was – if they ever built the ACE – something that could actually be tried out.

Except everyone knew that computers were for doing arithmetic. Sums, more sums, complex sums, big sums … machine learning was self-evidently fantastical nonsense. If any further evidence were needed that Alan Turing was fantasising, you just needed to read the section headed ‘Man as Machine’:

One way of setting about our task of building a ‘thinking machine’ would be to take a man as a whole and to try to replace all the parts of him by machinery … In order that the machine should have a chance of finding things out for itself it should be allowed to roam the countryside, and the danger to the ordinary citizen would be serious … Instead we propose to try and see what can be done with a ‘brain’ which is more or less without a body providing, at most, organs of sight, speech and hearing …

Alan Turing was talking about robots. Back at the Laboratory they had a good laugh: ‘Turing is going to infest the countryside with a robot which will live on twigs and scrap iron!’6 It was a terrible mistake. By conflating the ideas of machine learning and robots (cybernetics) Alan Turing had – possibly for all time – made it legitimate to dismiss any considered debate about machine intelligence as a foray into science fiction. No matter that he was trying to get his readers to put robots and intelligent machinery into different conceptual containers, so they could focus on the intelligence capabilities of the software; once this particular genie was out of its bottle, there was no putting it back.

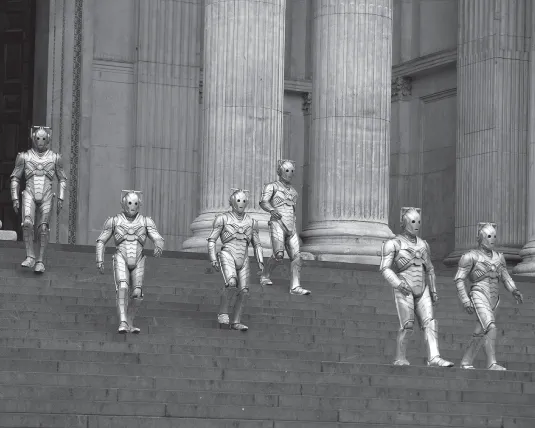

Alan Turing had just invented what I call the Robot Fallacy. It was part of the same piece that allowed newspapers to call a computer an ‘artificial brain’; but contemporaneous scientific research was also looking at the new discipline of cybernetics – control and perception of inanimate moving machines, or what you might call ‘robots’. Cybernetics was the brainchild of the American academic Norbert Wiener, whose book of that title was published in 1948. Artificial people were going to be created and they were going to have artificial brains, and that, simply put, meant that ‘thinking machines’ were the same thing as robots, whatever their dietary preferences. Even in 2016, the House of Commons Science and Technology Committee investigating robotics and artificial intelligence quoted a comment that ‘there is no AI without robotics’ to justify their own conflation of the topics.7 (Perhaps, though, the issue is more one of semantics. These days, the word ‘robot’ can just as easily refer to a disembodied AI which dispenses services over a phone or a computer as to a scrap-iron-eating Cyberman. But I still think ‘robotics’ is the science of cybernetics, not AI.)

Cybermen (which may be robots, but are probably actors) from the 2014 Doctor Who series. (Adrian Rogers / BBC / Everett Collection / Alamy)

The Robot Fallacy has evolved subtly since 1948. I am often privileged to be asked to attend and sometimes to speak at gatherings where artificial intelligence is on the agenda, since the begetter of the whole business, Alan Turing, is usually present in spirit (and on the agenda himself) at these events. Frequently, someone in the audience will ask about the dangers of super-intelligent machinery – a subject which deserves proper study – but almost invariably the experts giving the lectures will say something along the lines of, ‘I think you watch too many science fiction movies; robots aren’t about to take over the world.’ With that cheap laugh we can move on and avoid a difficult discussion about controls and limitations in a rapidly growing area of research. If it happens to you – don’t stand for it, complain that you didn’t mention robots, and demand a proper answer to your question.

Back in 1948, Alan Turing’s paper, called ‘Intelligent Machinery’, was spiked. The NPL is now rather proud of it, but it was not until 1968, fourteen years after Alan’s death, that it was first published.8 Alan Turing wanted to be heard on the subject of machines and intelligence, but nobody wanted to listen. Alan was bored and frustrated, but his old teacher and mentor came to the rescue. The sabbatical year was spent at Cambridge, where Alan bumped into M.H.A. Newman, who had first put the idea of machine processes for algorithms into his head back in 1935, and now Newman suggested that Alan might come to work in Newman’s new ‘Royal Society Computing Machine Laboratory’ in Manchester. Alan jumped at the idea, and jumped ship. The rest of his life was spent in Manchester.

Newman’s Manchester computer was ‘actually working 8/7/48’ – Alan put this little dig at NPL’s interminable delay into his ‘Intelligent Machinery’ paper – and ran its first routine on 21 June 1948. In fact, the machine was only a ‘baby’ – a proof-of-cncept device, rather like the Pilot model of the ACE which Alan Turing disparaged as a distraction from the full-size ACE which might never get built. But another, bigger Manchester machine was coming into being, and when that came into service later that year there was another round of fun in the newspapers.

The story is quite well known. Computers were for sums, even old sums: so the Manchester computer had been put through its paces on an old, unsolved problem dating from the 1600s. This was to find which numbers of the form 2n–1 are prime. Doing the calculations by hand was immensely tedious and probably pointless. But in binary, numbers like this all look like 111111… and are eminently suitable for testing on a computer with minimal memory capacity. (It was Newman’s idea to choose this problem – itself a brilliant mathematical insight.) Not only did the program work, and find some new prime numbers in the series, but it had sparked the debate on whether the computer could be said to ‘think’. In weighed the university’s professor of brain surgery, Sir Geoffrey Jefferson, CBE, FRS, MS, FRCS, who denied it in a speech widely reported in the papers in early 1949. Sir Geoffrey waxed lyrical about the distinction between human-ness and machine-ness:

The schism … lies above all in the machines’ lack of opinions, of creative thinking in verbal concepts … Not until a machine can write a sonnet or compose a concerto because of thoughts and emotions felt, and not by the chance fall of symbols, could we agree that machine equals brain – that is, not only write it but know that it had written it. No mechanism could feel (and merely artificially signal, and easy contrivance) pleasure at its successes, grief when its valves fuse, be warmed by flattery, be made miserable by its mistakes, be charmed by sex, be angry or depressed when it cannot get what it wants.9

There was more in the same vein, but the reporters cottoned on to the fact that the university had built a ‘brain’, and the game was on.

Unhappily for those who thought that computers were for sums, The Times got hold of someone called Turing at the Computing Laboratory, and then there was this:

THE MECHANICAL BRAIN

ANSWER FOUND TO 300 YEAR-OLD SUM

From Our Special Correspondent

… the Manchester ‘mechanical mind’ was built by Professor F.C. Williams, of the Department of Electro-Technics, and is now in the hands of two university mathematicians, Professor M.H.A. Newman and Mr A.W. Turing [sic]. It has just completed, in a matter of weeks, a problem, the nature of which is not disclosed, which was started in the seventeenth century and is only just being completed by human calculation … Mr Turing said yesterday: ‘This is only a foretaste of what is to come, and only the shadow of what is going to be. We have to have some experience with the machine before we really know its capabilities. It may take years before we settle down to the new possibilities, but I do not see why it should not enter any one of the fields normally covered by the human intellect, and eventually compete on equal terms. I do not think you can even draw the line about sonnets, though the comparison is perhaps a little bit unfair because a sonnet written by a machine will be better appreciated by another machine.’ Mr Turing added that the university was really interested in the investigation of the possibilities of machines for their own sake. Their research would be directed to finding the degree of intellectual activity of which a machine was capable, and to what extent it would think for itself.10

The elephant had now been well and truly unleashed. It was roaming the countryside and causing distress all round, and not just to the academics and administrators at Manchester University. Newman had to write to The Times to explain the nature of the 300-year-old sum and the real limitations of the computer. But the point was that people...