![]()

1

Czechoslovakia, Czecho-Slovakia and the Munich Agreement

Mary Heimann

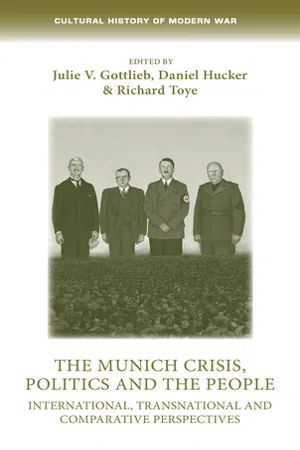

In Czech – which is not the same thing as Slovak – popular memory, the agreement that was signed at Munich in the small hours of the night 29–30 September 1938 was a national catastrophe, a disaster comparable to the loss of Bohemian independence in 1620 or the crushing of the Prague Spring in 1968. The infamous document, signed by Hitler for Germany, Mussolini for Italy, Daladier for France and Chamberlain for Britain – but, crucially, not Beneš for Czechoslovakia – is seldom mentioned in neutral terms. The treaty is referred to, with irony, as the ‘Mnichovská “dohoda”’ (Munich ‘Agreement’), the scare quotes used to indicate that there was no ‘agreement’ from the country whose territory was being decided. Or it is described, with bitterness, as the Munich ‘diktát’, the foreign loanword used to show what language the dictator spoke and to trump Germanophile notions of a ‘Versailles diktát’. In the equally common formulation ‘Mnichovská zrada’ (Munich betrayal),1 the invisible finger of blame is pointed at the British and French, the turncoat allies, rather than at the Czechs’ traditional enemies, the Germans. The expression ‘O nás, bez nás’ (About us, without us), which is understood to refer specifically to the Munich Agreement, accentuates the injustice of Czechoslovakia having been left out of the deliberations.2 The intended moral is clear: they, not we, were responsible for this terrible episode.

The notion that Czechoslovakia was sacrificed, martyred, even crucified, has particular resonance across Central Europe, where an originally Catholic trope became a nationalist commonplace. The poignant, recurrent refrain in František Halas’s 1938 poem ‘Zpěv úzkosti’ (Song of Anxiety), ‘Zvoní, zvoní zrady zvon / čí ruce ho rozhoupaly / Francie sladká hrdý Albion / A my jsme je milovali’ (the bell of betrayal tolls / whose hands swung the bell? / sweet France, proud Albion / and we had loved them), evokes indignation at the Allies’ treachery and pity at Czechoslovakia’s plight: to have been betrayed by those it had loved and trusted, but could trust no more. Halas’s mournful verses, memorised by generations of Czech schoolchildren, also refers to ‘clenched fists’, an allusion to mobilisation and the widespread perception that the Czechoslovak people, prepared to fight for their country, were denied that satisfaction by President Beneš’s acquiescence.3 In Czech especially, the words ‘Munich’ and ‘betrayal’ go together, almost like synonyms. The associations are so entrenched that the Czech Wikipedia dictionary-style entry (which is translated into Slovak word for word) gives three alternative names for the four-power pact signed at Munich in September 1938: dohoda, zrada, diktát (agreement, betrayal, diktat).4 Unsurprisingly, Czech and Slovak accounts agree that Munich was a disaster. What came next is more contentious, since Fr Jozef Tiso’s Slovak Republic of 1939–45, which was closely allied to Nazi Germany, was the first ever Slovak state.

In Czech newspapers, magazines and television and film documentaries, as well as in popular histories and school textbooks, the events of September 1938 are endlessly rehearsed. The question as to whether or not it would have been better to refuse to accept the Munich diktát and fight alone, holding out long enough to be joined by the Soviet Union, is perpetually debated: not only in books, magazines and documentaries, but also in pubs and around dinner tables. What if things had turned out differently? is the title of both a popular Czech counterfactual paperback and a prime-time Czech Television TV series.5 One of the most lavishly funded recent portrayals of this moment of truth appeared in the 2013 TV documentary-drama series České století (The Czech Century). In the episode called ‘The Day after Munich’, a rather wooden Czechoslovak President Edvard Beneš is shown having to cope with the outrage brought to him by his chiefs of staff. ‘I tried everything’, the president explains, ‘I kept offering different solutions. One plan after another. A third plan. A fourth. Autonomy. Then I offered a fifth plan. But they kept wanting more …’. General Vojtěch Luža interjects: ‘the British gave us hope. They kept winking at us as if to say that you had everything under control’. General Lev Prchala bursts out at Beneš: ‘You need to name a new government – a military government – and mobilise. We need to show the world – they are testing our strength, don’t you understand?’ Beneš: ‘But we are weak. Without France and Poland, we are weak.’ Prchala responds: ‘You are weak! We can’t just accept this. If we don’t want to be slaves, we have to defend our honour.’6 But Beneš, pale and drawn, refuses to give the order. Instead, he accepts the loss of the Sudetenland and prescribed ‘settlement’ of Hungarian and Polish grievances as a fait accompli.

Czechoslovakia’s reputation as an ‘island of democracy’ in a hostile, totalitarian sea, a stalwart nation whose interests were shamefully betrayed by its would-be protectors – the story that was to become such an important trope in Allied wartime propaganda and beyond – began to be fixed as early as 1938.7 In now familiar documentaries, compilations of newsreel and voice-overs with titles like ‘the Road to War’ or ‘the Price of Appeasement’, the signing of the Munich Agreement at the end of September 1938 is invariably followed by images of German troops marching into Prague in mid-March 1939, as if one act immediately followed the other, without the intervening months.

The implied or stated connections between the signing of the Munich Agreement and the collapse of the Czechoslovak state have come to be popularly linked roughly as follows. After Munich, Hitler promised that he had no further territorial demands to make. Chamberlain returned to Britain in triumph, claiming to have preserved peace. On 15 March 1939, German troops marched into Prague while France and Britain – signatories to the Munich Agreement and Czechoslovakia’s closest allies – stood by. The implication is that Hitler had broken the terms of the Munich Agreement, and the other signatories should therefore have defended Czecho-Slovakia’s post-Munich borders. Only after Hitler attacked Poland, on 1 September 1939, did France and Britain finally declare war on Germany. Czechoslovakia, so the familiar moral of the story goes, had been sacrificed in vain, made to pay for the Allies’ naive trust in Hitler’s promises and policy of appeasement. Those who sought to evade war inadvertently helped to bring it about. Worst of all, because Germany was simply handed over the strategically and militarily important parts of the Bohemian Crown Lands, the war lasted longer, and was even more horrifying, than necessary.

In Czech, the notions that Munich was a terrible wrong inflicted by the French and British, that the Czech people were ready to fight but prevented from doing so by Beneš’s acceptance of the Munich diktát, and that this humiliation had serious consequences for the Czech nation’s self-belief and self-respect, have a particular salience. This is because the so-called Munich Complex has been used widely to explain the Czechs’ subsequent acceptance of authoritarian regimes, first of the extreme political right and later of the extreme political left. The rapidity with which democracy was abandoned after Munich, the extent of wartime collaboration with the Nazis, the brutality with which German-speakers were expelled after the Second World War, the ease with which the Communists came to power in 1948, and the speed with which ‘normalisation’ was reimposed by the Czechoslovak Communist Party after the Prague Spring: all these sensitive topics have been excused or explained as indirect consequences of Munich. Those dark chapters which cannot so easily be made to fit the Munich narrative – for example, the post-war expulsion (‘exchange’) of Hungarians, the pre-war persecution of Roma (gypsies) or the state-sponsored discrimination against Jews by Slovak and Czech authorities before 15 March 1939 – remain largely absent from both public discourse and official memory.8

The Munich Agreement was interpreted differently under the varied Czecho-Slovak, Czech, Slovak and Czechoslovak regimes which followed the fall of the First Czechoslovak Republic at the end of September 1938. Two underlying meta-narratives continue to dominate. The first meta-narrative, which dates from the Second World War, was consciously developed and promoted by ex-Czechoslovak President Beneš, as part of his tireless wartime campaign, as a voluntary exile in the USA and in Britain, to restore the Czechoslovak state to its pre-Munich borders, annul the Munich Agreement, return to power, realign the country’s security alliances, and remove the non-Slav minorities (above all Germans, but also Hungarians and remaining Jews) from a reunited Czech and Slovak post-war state.9 This wartime narrative was itself built on what Andrea Orzoff has aptly termed the modern ‘myth of Czechoslovakia in Europe’ as put forward during the First Republic by the Castle Group (a close circle of advisers, intellectuals and politicians surrounding founding father and first Czechoslovak president T.G. Masaryk and his disciple Edvard Beneš), according to which Czechoslovakia was ‘one of the most enlightened, developed and progressive democracies east of the Rhine’ and T.G. Masaryk a great humanist and democrat.10

The second meta-narrative, developed during the socialist/communist period after the Second World War, built on pre-existing Castle narratives of Czechoslovak exceptionalism and post-Munich disenchantment with multi-party democracy, but introduced new criticism of the ‘bourgeois’ aspects of the First Czechoslovak Republic. ‘The Communist version of the Munich story’, as Karel Bartošek observed during what turned out to be the Czechoslovak Communist regime’s last year in power (1989), ‘practically never wavered from the single theme that Czechoslovakia was betrayed, not only by “the western bourgeoisie” but also by “domestic reactionaries” such as the “traitors among the right-wing socialist leaders and the Castle bourgeoisie.”’11 This device enabled Czech patriotism, nationalism and disillusionment with Munich all to seem supported by communism.

Although many communist set interpretations were discredited and overturned after the 1989 revolution, removing symbols of the Soviet liberation of Prague proved controversial. In the end, some – most notably Tank 23, which once stood on a concrete plinth in the middle of ‘Tank-Drivers’ Square’ in Prague – were removed; while others remain, undisturbed, such as the statue Brotherhood, depicting a feminised Czech soldier embracing and presenting a bouquet of lilies to a manly Soviet liberator, outside Prague’s main railway station. Similarly, while some Czech scholars cast doubt on the Soviet Union’s genuine readiness to intervene on Czechoslovakia’s behalf in 1938, most reproduce, unchallenged, the Communist-era interpretation in which the bourgeois, Western allies (France and Britain) betrayed Czechoslovakia whereas the Soviet Union – alone of all the state’s allies – remained true.12

In 2015, in anticipation of the eightieth anniversary of the signing of the Munich Agreement, the Czech film director Petr Zelenka released a semi-comedy, Ztraceni v Mnichově (Lost in Munich). The film opens with familiar newsreel images from 1938 of demonstrations outside the Czechoslovak parliament, mobilisation, and the signing of the four-power pact. These well-known images are accompanied by highly emotive orchestral music, all racing strings and thundering timpani, with a grim voice-over. ‘Munich, 1938’, begins the narrative. ‘A stirring drama of betrayal. The event that led directly to the unleashing of the Second World War. Ten days that decided the fate of the Czechoslovak nation for long years to come.’13 After an hour and a half of post-modernist romp, centred around the making of a film within a film featuring Eduard Daladier’s talking parrot, ‘Lost in Munich’ ends with another few minutes of archive footage, this time without voice-over, allowing us silently to witness the Czech governm...