- 178 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Historic Costuming

About this book

This classic, historical book is a detailed and comprehensive look at the history of historic costuming which is perfect for anyone with a professional interest in theatrical production or design. Extensively and beautifully illustrated this is a worthy addition to any book shelf. Many of the earliest books, particularly those dating back to the 1900s and before, are now extremely scarce and increasingly expensive. We are republishing these classic works in affordable, high quality, modern editions, using the original text and artwork.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

HISTORIC COSTUMING

CHAPTER I

COSTUMES, COLOUR, AND PRODUCTIONS

THE age-old story of this still mysterious world contains no pages more fascinating than those which reveal how men and women have clothed themselves, with what devices they have decorated their limbs, in what gay colours they have arrayed their bodies, and into what fantastic shapes they have twisted and twirled the forms their Creator gave them.

Ever since the day when Eve made a girdle from the leaves of the nearest tree, Woman has sought to attract and delight her Adam with similar tricks, and if to-day she no longer is content with the simple beauties of Nature and must call in to her aid the developments of an artificial and mechanical age, her aim is, nevertheless, the same as that of her first parent.

To-day clothes have returned to their first precedent. In Eden it was Woman who was the adorned and decorated one. Her spell of supremacy over Man was short-lived. Adam imitated her leafy garment and outshone her speedily. Taking another leaf from Nature’s book, he gazed with awakened eyes on the animals and birds, and discovered that to the males were given the brightest colours, the gayest shapes, and the most impressive forms. Then for eighteen hundred years of the Christian Era Man was the more brilliantly costumed.

Woman, whilst she was but little behind in the race for sartorial supremacy, never outran her partner and won that race until the last of the Hanoverian Georges dazzled Europe with the massiveness of an intellect that could devise an eight-inch shoe buckle.

Prince Florizel also made fashionable the black suit—and men have mourned ever since—though whether for the suit or for the character of its inventor we leave the historians to decide.

Woman now heads the bill. Her shape alternately swells and slims, lengthens and diminishes, according as her fancy takes her—and man in his sober duns, greys, and blacks, looks on admiringly. Perhaps the wheel will turn again. There are signs, in the cautious revival of colour and shape, that modern man is tired of being the uninteresting foil to woman, and we may yet see him again arrayed in all the glory of the rainbow.

Adown the procession of the ages flit many famous people. The history of costume conjures up for us the figures of great men and women. Indeed, it is impossible to separate the two. Who can think of Cardinal Wolsey without his bright red cape and biretta? Who remembers Queen Elizabeth without her great lace ruff? Verily, the clothes have become the symbols of the people; and the lesser has usurped the place of the greater. What is Wellington but a pair of boots, or Gladstone but a travelling bag? Raleigh with his cloak, Henry VIII with his falsely broad shoulders, King Charles with his feathered hat, Lord Byron with his open collar, James the First in his padded plus fours—we cannot recall the men without their clothes. The clothes are the men. They stamp their personalities upon us.

Then are not clothes a fascinating part of history and of life? Will not their study well repay us in forming a prelude to our understanding of human nature, without which knowledge it is impossible to advance far in the battle of life? Let us then to business.

As clear-cut a description of the different periods as is possible with such a complex and pliable subject as costume will be given. In order to make reference quick and easy, the dress of each reign or period will be summarized in tabular form in each chapter preceded by fuller descriptions and illustrations. It will thus be possible, once the descriptive matter has been mastered, for the reader to turn to the summary and immediately to grasp what is wanted without having to re-read the whole chapter, as is the custom with most costume books. Indeed, writers on this subject are notoriously vague, and it is by no means easy to select the dress of a special epoch readily from current works. Writers have great reluctance to date the costumes sufficiently precisely. This springs partly from the undoubted fact that dress changes so imperceptibly and gradually—being advanced in the larger centres of population, and old-fashioned in the country places—that it is never safe to dogmatize too severely as to what was or was not worn at any given date.

WOMAN OF THE PERIOD OF ELIZABETH

Nevertheless, the artist or actor is not expected to be an antiquary. He is expected to adopt a costume that is correct. I will give the normal type of dress of its date, without the “buts” and “ifs” of the archaeologist. The risk of dogmatizing must, therefore, be incurred in the interests of practicality. This risk is really slight when it is borne in mind that the purpose of the costume is to please those who see it, who are never so critical as the members of a learned society. People to-day, with the spread of education, know broadly what costumes are “right,” and they naturally resent the production of a period play or the painting of a period picture that is not in the main correctly costumed. Bearing these points in mind, all that is necessary will be given.

We must remember that what the medieval mind loved above all things was colour. The people of the Middle Ages had a sound artistic sense that seems to have sprung naturally from them. It was partly due, no doubt, to the fact that they were a race of craftsmen. The coming of the machine struck a deadly blow at craftsmanship, and men turned to the machine-made article which resulted in the machine-made mind. Luckily, there is to-day a revolt from the mastery of the machine and the domination of the trade designer. This is all to the good. We are returning to our earlier good taste, and the dressing of any play should be prepared on an ordered scheme of colour.

Have as much colour as you can by all means, but avoid harsh and clashing effects. The cast of a play may indeed be dressed in clashing colours, provided that they do not appear together on the stage. Lovely effects can be obtained by blending the minor characters in different shades of the same colour, whilst making the leading characters outstanding with vivid contrasts. Nothing looks better than to have retainers dressed alike, whilst medieval crowds may be as bright and variegated as possible, and little attention need be paid to avoiding clashing, if a goodly proportion of browns and greys are included for the menfolk. The right use of black as a foiland an accentuator should be recollected.

MAN OF THE PERIOD OF CHARLES I

In crowd work the producer should mark the places where he desires his supers to stand having regard to their dress colours. For this he must have full knowledge of the colours of the dresses that will be provided. He can then allot them in mind from the start, and it will be easy at each rehearsal to get the characters into the places they take for the actual performances.

CHAPTER II

THE GREEKS 550 B.C.-322 B.C.

DURING the 2,500 years of Greece’s power costume varied, and in the earlier period was so scanty as to be useless for stage purposes. The Greeks knew the advantage of sun and air reaching the skin, and their clothes were designed so as to allow for this, and also to give great freedom for athletic exercises—two points that we should do well to imitate to-day. The great Greek dramas of the classical period range from 550 B.C. to 322 B.C. It is this period which will be wanted for theatrical purposes and which is here described.

GREEK WOMAN (Indoors)

DRESS

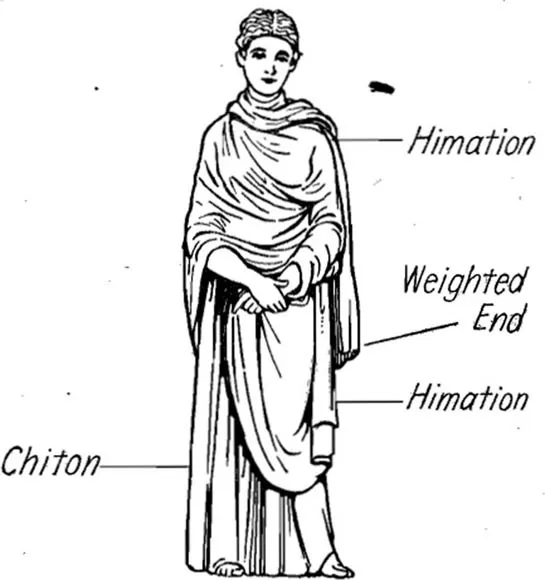

The Doric Chiton (men and women) was a tunic made from a rectangle one foot longer than the wearer’s height and of width twice the distance from finger tip to finger tip with arms outstretched. It was made of wool, and the favourite colours were purple, red, saffron, and blue. To adjust it, the extra foot in length was first folded over, then the long rectangle was folded in half and draped round the body with the fold on the left side. Back and front were caught together with pins at the shoulders, and it was girdled at the waist with a slight overhang there. Thus two loopholes were left at either side for the arms to pass through. The length was shortened by pulling it over the girdle to form a blouse called the Kolpos. The arms were left bare. The loose ends at the right side were not fastened together, but were left free for exercise; for theatre purposes these should be stitched together. The over-fold may be embroidered with Greek Key and other designs and the loose end (on the left side) should be weighted with beads. This end should fall slightly lower than the overfold edge on the left side.

SLEEVE OF IONIC TUNIC

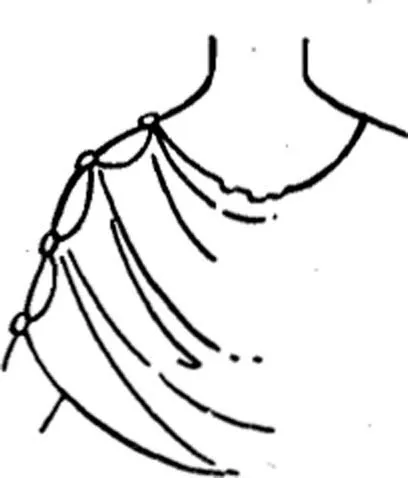

The Ionic Chiton (men and women) was a similar tunic without the overfold at the top, but made of linen or cotton, and larger and fuller, showing more folds. It was also distinguished by having sleeves made by holding the back and front of the chiton together at intervals with small pins at the arm openings. An overfold was sometimes, but rarely, added.

Skirts must not be worn under these tunics, as the limbs must show in outline, and the draping should be done with the greatest care. It was one of the chief duties of the slaves to adjust these beautifully.

The Super Tunic (men and women) reached to the waist and was worn for extra clothing. Generally speaking, the tunics of the men were shorter than those of the women.

The Pallium (men) was a large cloak worn by philosophers, who also wore the Tribon, a rough cloak of black or brown.

The Peplum (men and women) was about 4 yds. long by 2 yds. wide, and was passed twice round the body under the arms. It was then brought up over the shoulders, and secured by closely winding it about the body, or it was pulled over the he...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Dedication

- Foreword

- Contents

- Colour Plates

- Chapter I Introduction, Costumes, Colour, and Productions

- Chapter II Greeks 550 B.C.–322 B.C.

- Chapter III Romans 509 B.C.–A.D. 324

- Chapter IV Saxons 460–1066

- Chapter V Normans, 1066–1154

- Chapter VI Plantagenets, 1154–1272

- Chapter VII The Three Edwards, 1272–1377

- Chapter VIII Richard of Bordeaux, 1377–99

- Chapter IX The Three Henries, 1399–1461

- Chapter X Yorkist, 1461–85

- Chapter XI Henry VII, 1485–1509

- Chapter XII Tudor, 1509–58

- Chapter XIII Shakespeare’s England, 1558–1625

- Chapter XIV The Martyr King, 1625–49

- Chapter XV Puritanism, 1649–60

- Chapter XVI Restoration, 1660–89

- Chapter XVII Dutch William, and After, 1689–1727

- Chapter XVIII George II, 1727–60

- Chapter XIX The Man of Fashion, 1760–1820

- Chapter XX Empire and the Dandies, 1820–37

- Chapter XXI The Crinoline, 1850–60

- Chapter XXII Grosvenor Gallery, 1870–80

- Chapter XXIII Noah’s Ark, 1880–90

- Chapter XXIV The Nineties, 1890–1900

- Chapter XXV Edward VII 1901–10

- Chapter XXVI Clergy at Mass

- Chapter XXVII Clergy in Choir and Street

- Chapter XXVIII Armour Fashions Summarized

- Appendix The Evolution of Styles

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Historic Costuming by Nevil Truman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Design & Fashion Design. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.