![]()

1

The currency of adaptation: Art and money in silent cinema (1899–1929)

Andrew Watts

The enthusiasm of filmmakers for adapting French literature is as old as the medium of cinema itself. After brothers Louis and Auguste Lumière had exhibited their cinematograph for the first time in 1895, others were quick to recognize the potential for using this new technology to create fiction as well as documentary films. The period between 1899 and 1929 – the year in which the first sound film, The Jazz Singer (dir. Crosland), was released in France – subsequently witnessed the emergence of a vibrant interest in recreating French literary texts for the screen. As the nascent medium hungered for new material, adaptations represented a quick and inexpensive way of making money and promoting cinema as a form of entertainment. Moreover, adapting the works of canonical writers such as Balzac, Hugo and Zola served as a reliable means of attracting spectators, who were often curious to see how re-imaginings of classic texts appeared on film. The present chapter explores these early drivers of cinematic adaptation by drawing on key French literature films produced in France, Germany and the United States. More specifically, it uses the concept of currency – in both a literal and figurative sense – to ask why French literature exerted such a powerful fascination for silent cinematographers and how they, in turn, reflected on the questions of art and money which shaped the early film industry.

In analysing the key reasons for which silent filmmakers adapted French literature, this chapter employs the idea of currency on a variety of interrelated levels. Most obviously, it defines currency as money and shows that the desire to amass profits was one of the strongest motives behind the reinvention of French literary texts for the silent screen. At the same time, however, my discussion argues that money was merely one of a number of currencies that early cinematographers used and actively pursued. First, as cinema strove to establish its credibility as a new medium, it aspired to garner currency in the Bourdieusian sense of cultural value and legitimacy, particularly in comparison with the more prestigious medium of the theatre. Second, cinema sought to acquire its own creative currency and to develop artistic techniques and innovations that were genuinely cinematic as opposed to being derived from the well-worn conventions of the stage. Third, this chapter interprets some of the early stars of silent cinema as human currencies, commercial assets who were used both to promote the films in which they appeared and to generate large box office revenues. Finally, currency can be viewed as a key subject of silent adaptations of French literature. Together with its associated themes of circulation, rotation and exchange, the subject of currency captivated many early cinematographers, who identified it as a conduit through which to reflect on the development of their medium.

By exploring this array of literal and figurative currencies, this chapter rethinks the long-standing critical assumption that silent filmmakers embraced adaptation merely for financial gain. Making money was of course a key objective of the early film industry, and studios were often prepared to break the law in their pursuit of profits. As Jane M. Gaines has argued, plagiarism and financial profiteering were especially rampant during this period:

Within the context of silent adaptations of French literature, this characterization of early cinema as an unscrupulous, money-orientated industry is by no means inaccurate. In 1910, for example, Alice Guy’s Esmeralda (1905), the earliest known cinematic version of Hugo’s Notre-Dame de Paris (1831), was pirated by two companies in the United States, Vitagraph and Selig, which reissued it under the titles Hunchback and Hugo the Hunchback, respectively.2 By representing early filmmakers as plagiarists and profiteers, scholars have nevertheless tended to ignore the much wider range of artistic, cultural and financial imperatives that drove the practice of adaptation during this period. In so doing, they have also perpetuated old critical stereotypes of adaptation as a parasitic activity that exploits the prestige of canonical literature for commercial ends.3

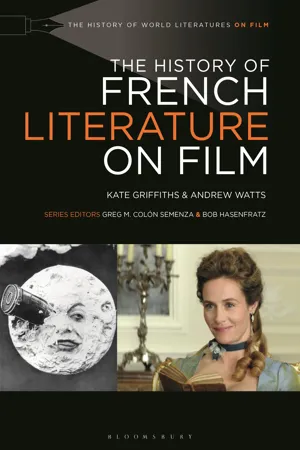

The first part of this chapter focuses on French cinema between 1899 and the end of the First World War, since analysing the notion of currency during this period deepens our understanding of the adaptive impulses that underpinned the silent era. This opening section considers the work of early filmmakers Georges Méliès and Alice Guy. In particular, it shows how they used adaptation not only to generate commercial revenues but also to give cultural currency to a medium that had its origins in fairgrounds and popular theatre.4 The second part of this chapter explores the adaptation of French literature in the United States between 1913 and 1921. Through its discussion of this key period in which North America established itself as the pre-eminent commercial power in world cinema, this section examines how silent filmmakers in the United States used adaptation to bring artistic, cultural and monetary currency to the cinema. It reflects more specifically on the role of stardom in films such as The Count of Monte Cristo (1913, dir. Porter), which sought to garner substantial profits by casting well-known stage actor James O’Neill in the title role. Finally, this chapter returns to European cinema and to the tension between art and money that can be observed in both French and German adaptations during the 1920s. In L’Argent (Money) (1929), especially, Marcel L’Herbier reflects self-consciously on the creative and commercial drivers behind the production of his film, not least through his emphasis on images of rotation and monetary exchange.

In studying the importance of art and money during the silent era, this analysis draws on the work of key film scholars including Richard Abel, Tino Balio and Susan Hayward, whose research enables us to situate the practice of cinematic adaptation within the broader historical context of the period. However, in contrast to the critical approach favoured by these earlier scholars, who have tended to focus on the diachronic history of silent film, this chapter explores the fundamental role that adaptation played in the early development of cinema as a medium. In my discussion of films spanning the advent of the cinematograph to the arrival of sound film, I argue that the desire of early filmmakers for currency – whether artistic or financial, literal or metaphorical – was integral to establishing the new medium. This desire for currency is of course not unique to the silent era. Throughout the subsequent history of cinema, filmmakers have continued to be motivated by the pursuit of money and artistic innovation. As this chapter shows, however, the interaction between different forms of currency takes on a specific resonance in the context of silent cinema. In the early film industry, currencies were the source of a productive tension that drove the technical development of cinema and fuelled the medium’s eventual awareness of itself as an art form.

Adaptive commerce and the pursuit of cultural currency in early French cinema (1899–1917)

For the earliest filmmakers in France, money appeared as a key driver of cinema’s enthusiasm for adapting French literature and its attempts to establish itself as a narrative medium. Financial imperatives helped to shape the early development of cinema. This is particularly clear in the case of Georges Méliès, who was born in 1861 to a prosperous family of Parisian shoe manufacturers. Prior to embarking on his career as a cinematographer, Méliès had been employed in his parents’ business. In 1884, he travelled to London with a view to extending his family’s commercial contacts in the city. During his year-long stay in Britain, he developed an interest in theatrical illusions, in particular those of the popular magician David Devant. Such was his fascination for stage magic that following his return to Paris, Méliès sold his share in the family business and combined these funds with his wife’s dowry to purchase the Théâtre Robert-Houdin in 1888. Over the next seven years, the theatre staged numerous magic shows and féeries, fantastical plays which combined elements of music, dance, acrobatics and pantomime whose aesthetic would greatly influence both Méliès’s own subsequent film production and the development of cinema as a medium more generally.

In providing Méliès with a financial platform to establish himself in the entertainment industry, money also proved crucial to his subsequent turn to filmmaking, adaptation in particular. In the hope of increasing revenues at the Théâtre Robert-Houdin by incorporating film screenings into his shows, Méliès attempted to buy a cinematograph from the Lumière brothers in December 1895. Eager to retain the commercial benefits of this new technology for themselves, the Lumières refused his offer of 10,000 francs, prompting him to acquire a more rudimentary projector known as an Animatograph from British inventor Robert William Paul. The Animatograph enabled him to show films at the Théâtre Robert-Houdin and, as he modified and improved the equipment, to build a new camera with the capacity to record images. In the early summer of 1896, Méliès made his first film, Une partie de cartes (Playing Cards), in which he, his brother Gaston and two of their friends are shown playing cards in what was a direct adaptation of the Lumière brothers’ earlier film Partie d’écarté (Card Game) (1895). By the end of the year, he had also begun construction on his own studio in the garden of his home in Montreuil, a structure he built to the same specifications as the stage at the Théâtre Robert-Houdin. With its large glass panels designed to provide sufficient light for filming, it resembled an oversized greenhouse. Money had enabled Méliès to launch his career in the theatre, and the commercial acumen that he continued to show thereafter was integral to his ambition to extend his work into film.

Literary adaptations formed a key part of Méliès’s plans to use film screenings to boost revenues at his theatre and ultimately sell his films to an international market. Not surprisingly, given his artistic passion for féeries, he drew extensively on the seventeenth-century fairy tales of Charles Perrault and recreated at least four of these stories for the screen during his career. The earliest of these adaptations was Cendrillon (Cinderella) (1899), based on Perrault’s 1697 tale of the same title. Totalling 120 metres in length, the six-minute film is described in the catalogue of Méliès’s Star Film Company as a ‘grand and extraordinary féerie in 20 tableaux’, a claim which rather overstates the number of sequences in the film by counting each plot element as a scene in its own right. Despite this exaggeration of the film’s complexity, Cendrillon was clearly an ambitious adaptation, it being the first of Méliès’s films to use multiple tableaux, with the narrative unfolding across six different sets and incorporating five scene transitions. The film also featured a large cast of dancers and extras which Georges Sadoul speculates might have been drawn – along with some of the costumes and décors – from a production of Cendrillon staged at the Théâtre Robert-Houdin in December 1897.5

If Méliès appropriated artistic materials from the stage in his adaptation of Perrault’s fairy tale, he also sought to highlight the technical dexterity of cinema as a new medium. Key to the cinematic quality of Cendrillon in this respect is its playful use of the substitution splice, in which two pieces of film are joined together in order to create the effect of people or objects appearing, disappearing or changing in some way. The first such splice occurs when the fairy godmother (Bleuette Bernon) materializes suddenly in the fireplace of Cinderella’s kitchen, where she proceeds to turn a mouse into a carriage driver and two larger mice into footmen. After Cinderella ...