eBook - ePub

Domesticating Resistance

The Dhan-Gadi Aborigines and the Australian State

Barry Morris

This is a test

- 264 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Domesticating Resistance

The Dhan-Gadi Aborigines and the Australian State

Barry Morris

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

In this fascinating study of the Dhan-Gadi Aboriginal people of New South Wales, Australia, the author combines the skills of a social historian with the detailed observation of a social anthropologist. In so doing he brings alive the contours of crude racism, as well as the more subtle expressions of paternalism, bureaucratic social control and educational and economic marginalization.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Domesticating Resistance by Barry Morris in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Human Rights. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Colonial Domination as a Process of Marginalisation

It is a truism to say that colonialism belongs to the domain of politics and economics. By its very nature, colonialism involves political conquest and economic exploitation. Yet it is more than this. Colonialism is also a cultural process. The colonial process in Australia, which decimated the original inhabitants, expropriated their traditionally-held lands and segregated them on small reserves, has only recently received attention. Previously, colonial discourse, masquerading as history, had insinuated the Aborigines’ complicity in their own demise; they had simply faded away (see Ward 1958; Blainey 1966; Mulvaney 1975).1 In correcting this impression, much of the recent material has revealed a great deal about Aboriginal resistance to colonial expansion. Indeed, new research reveals a complex and widespread pattern of Aboriginal resistance (see Reynolds 1981; Ryan 1981; Loos 1982). Yet, given the evidence of this more active rather than passive response by Aboriginal groups, there has been very little analysis, either of the savage culture that prolonged the process of conquest and dispossession, or of the distortions of human relations that the social processes of colonialism unleashed.

1 The general consensus until recently has stressed the cultural unpreparedness of Aborigines to come to terms with ‘modern’ Australia. Mulvaney’s statement illustrates this approach, ‘the unexpected challenge of the Europeans evoked no response in Aboriginal society because it overwhelmed all three factors of man, land and animals in a balanced economy’ (1975: 242). Blainey refers to the ‘relatively mild threat of attack from Australian Aborigines’ (1966: 132), while Ward suggests that ‘one difficulty the Australian pioneers … did not have to contend with was a warlike native race … They [Aborigines) were amongst the most primitive and peaceable people known in history’ (1958: 21). Such characterisations effectively wrote Aborigines out of colonial history.

The frontier culture of terror is an important dimension in this anthropological interpretation of the Australian colonial process. The questions asked have been largely formulated in Taussig’s (1987) significant work on colonialism in South America. The clues to this colonial process are found in the political and economic forces gener-ated by capitalism in its colonial form and in the colonists’ cultural representations of their own experiences. Few clues remain of the experience from the other side of the frontier, for those other voices were either dismissed or silenced. Their silence brings its own pained awareness of how successfully the colonisers have implanted their own images of the colonial process. In analysing this colonial discourse about Aborigines it is important to remember that the only knowledge we have of the ‘other’, of the object of the colonising process, was produced as part of the political act of colonialism. The remaining knowledge (official records, private letters, autobiographies) was manufactured in alliance with the forces of colonial oppression as malleable forms of understanding lending themselves to legitimating the process.

1.1. The Political Economy of Settler Colonialism in New South Wales

The political economy of the colonisation of NSW generated a number of distinctive features. What differentiates it from Wolpe’s (1975) ‘normal colonialism’ is the virtual absence of exploitative relations associated with trade, labour and/or the production of specific raw materials. The colonising powers in NSW were not concerned with establishing trade relations or labour relations but, as Hartwig (1978) points out, with expropriating Aboriginal land, which was not seen as anyone’s, for European settlers. The latter is, of course, a distinctive historical feature of colonisation in the Americas and, more particularly, the United States and Canada (see Bee and Gingerich 1977; McNickle 1973; or Lithman 1978). As the colonisers exercise control over the colonised peoples while occupying the same territory, settler colonialism is by definition associated with internal colonialism (Wolpe 1975). This is the case whether the coloniser remain a minority with exploitation of indigenous labour as the predominant relationship, as for example in South Africa, Kenya and Rhodesia (Zimbabwe), or whether the indigenous population is reduced to a territorial minority and the expropriation of indigenous land is the major basis of relations, as for example in Australia, New Zealand, Israel, the United States and Canada.

Emergent colonial relations in NSW during the early nineteenth century were characterised by the absence of any formal administrative control over the indigenous population. (It was not until the 1880s that a systematic policy of intervention was developed and rudimentary forms of control were applied to the surviving Aboriginal populations.) These specific features of the colonial process in NSW were directly related to the rapid expansion of the wool industry from the 1820s, which provided the basis of the European economy, and the integration of the colony into the world economy as a supplier of raw materials.

The generative aspect of this economic relationship between the settler colony and its metropolis, Britain, was based on capital invest* ment in the land-extensive production processes of pastoralism. The economy of NSW developed as a supplier of raw materials for the British Empire. It rapidly expanded through its ability to attract British capital. The wool industry attracted a considerable amount of capital investment for most of the nineteenth century. For example, whereas in 1822, 172,000 pounds of wool were being exported for use in the expanding English woollen industry, by 1830 this figure had risen to 899,750 pounds (Morrissey 1970: 50). As Butlin (1968: 225) puts it, ‘The decade between 1830 and 1840 was a period of extraordinarily rapid economic growth in which immigration and capital import furnished the material for a vast geographical expansion of the wool industry/ (Emphasis added throughout unless otherwise stated.) The extent of this ‘extraordinarily rapid growth’ in wool exports to Britain is shown in the following figures. Between 1830 and 1836 wool exports to Britain increased fourfold to 3,693,800 pounds (Roberts 1964: 359). Over the following years the spectacular rise in wool production continued and by 1844 had again quadrupled to reach 13,542,000 pounds (ibid.). By 1834 wool had become the colony’s single most important export.

The rapid expansion of the pastoral industry depended on the growth in commodity production in the English textile industry. From the early 1800s the textile industry started to industrialise, with hand weavers progressively being replaced by power-driven machinery. Between 1820 and 1850, steam-driven looms became firmly established in the textile industry (Jeans 1972: 98). The use of new techniques revolutionised commodity production, for it made possible the mass production of ‘cheap cloths using coarse wool’ as well as ‘finer cloths of softness to appeal to expensive tastes’ (Morrissey 1970: 60). The effect of industrialisation was to lower the cost of production and to increase output through the establishment of a wider market for the English woollens industry.

In the search by British capital for cheaper sources of raw materials, Australian wool increasingly replaced that of Germany and Spain (Roberts 1964; Fitzpatrick 1969; Morrissey 1970; Jeans 1972). In 1834 Germany had 50 per cent of the English market, the Australian colonies 12 per cent and Spain 10 per cent (Roberts 1964: 46). In the 1840s the Australian share doubled to 25 per cent (1841) and had reached 50 per cent by the end of the decade (Fitzpatrick 1969: 85) Over the same period, the increase in wool exports to England grew from 12 million to 39 million pounds and the English market expanded from 49 million to 77 million pounds (ibid.). As he puts it, ‘the English woollens industry had increased its consumption by half but the Australian contribution to it of raw material had been multiplied by more than three’ (ibid.). This remarkable development continued throughout the nineteenth century.2 Such expansion occurred not through some naturally occurring process of expansion, but through the logic of capital, i.e. the calculated, ordered administration of commodity production. However, as I will show below, pastoral expansion was regulated and given impetus by the state (see also McMicheal 1979). The state scrupulously recorded and, hence, controlled the economic factors involved in the remarkable rate of increase and expansion of the fledgling economy. The only unquantified ‘factors’ were the amount of Aboriginal land and the number of Aboriginal dead that secured each spectacular incremental increase.

2 In the period between 1875 and 1880, the Australian (New Zealand included) market held 64 per cent of the British market of imported raw wool (Fitzpatrick 1969: 135). In terms of sheep numbers in NSW this can be translated as; 1861: 5.5 million sheep; 1871: 16 million sheep; 1881: 37 million sheep; and 1891: 62 million sheep (ibid. p. 137). Throughout the nineteenth century, the pastoral industry in NSW increasingly became the major supplier of wool to the English market.

The market rationality regulating pastoral expansion was not simply based on regularised investment of capital in wool production, but also on the transformation of profits from the wool industry into capital goods for consumption within the settler colony. It was European immigration that provided the basis for consumer demand and, hence, a broadly-based domestic market. In effect, the land-extensive production of the wool industry performed a double role in maintaining both the level of capital investment and the flow of capital-intensive goods. Expansion into the major part of NSW occurred in a compressed period of some 15 to 20 years as a result of what is called the ‘pastoral boom’ of the 1830s. This ‘pastoral boom’ was funded by British capital, overseen by British owners, serviced by British labour and based on the expropriation of Aboriginal land.3

3 The close links with British capitalism, generated by the pastoral boom, led to dependent development rather than underdevelopment. As Clark (1975: 51) defines it, ‘"Dependent development" described a situation where the development of one economy is influenced if not conditioned by the development and expansion of another. In the Australian case we see a situation where at times growth is impressive but at other times is clearly limited by our links with Britain; thus although we develop, the development process is only comprehensible in terms of our dependence in respect to Britain and to the timing and needs of her development process.’ Significant ‘metropolis’ control did not retard the development of this colonial economy (cf. Brenner 1977; Amin 1973).

The colonial economy of NSW was characterised by a strong demand for manufactured goods. It was this market, as Cochrane (1980: 5) argues, that provided the impetus for continued investment. ‘Colonial demand for imported manufacturing goods was a condition of capital investment. Australia’s export earnings in Europe were transformed into import demand. From the British standpoint, continued investment was contingent upon the sale of its manufactured goods in Australia and meeting its debts on the City of London.’ The economy was doubly tied to the wool industry. The structure of NSW’s economy provided the basis for capital investment in the pastoral industry and a growing domestic market for manufactured goods. The stimulus for internal consumer demand was generated by settler migration and the pastoral boom.

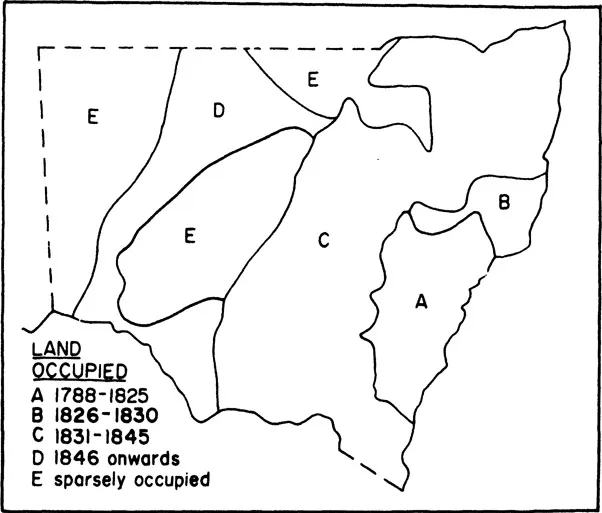

Central to the colonisation of the indigenous population of NSW was the connection between the inflow of capital investment and capital intensive goods, and the rapid development of a land-extensive economy. As Butlin (1968: 226) puts it, the ‘vast geographical expansion’ in NSW occupied ‘roughly half the total area’ in the 15 years between 1830 and 1845. Such rapid pastoral expansion swiftly expropriated the land from the indigenous population by removing or peripheralising them. This dramatic change was due to some extent to the ever-increasing numbers of Europeans, but more importantly to the large numbers of livestock, especially sheep, which radically transformed the physical environment of the region. Some 1,214,575 hectares were alienated for the use of European colonists by 1830 (see, for example, Table 1). This pattern of expropriation of Aboriginal land accelerated during the pastoral boom. Between 1830 and 1848 another 16,599,190 hectares were expropriated (Roberts 1964: 362; see also Map 1). On these pastoral leases some 2,358,000 sheep and 644,000 cattle were depastured (Roberts 1964: 362).

Map 1 . The Pastoral Occupation of New South Wales

| District | Year | Land Utilised Hectares | Stock Run | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cattle | Sheep | |||

| | ||||

| 1. Bathurst Plains | 1821 | 1,020 | 5,884 | 27,848 |

| 1825 | 37,100 | 21,906 | 92,067 | |

| 1828 | 119,225 | 49,290 | 165,786 | |

| 2. Hunter Valley | 1821 | 258 | 236 | 376 |

| 1825 | 27,449 | 4,495 | 8,909 | |

| 1828 | 622,465 | 46,805 | 119,391 | |

| 3. Argyle and St Vincent Districts | 1821 | 4,464 | 6,063 | |

| 1825 | 15,259 | 22,028 | 31,864 | |

| 1828 | 147,205 | 73,670 | 125,649 | |

Source: Adapted from Perry 1966:130–2

By contrast, the use of Aboriginal labour had never, in any systematic or sustained way, been seen to have had a role in the economic development of the colony.

In 1814 Governor Macquarie (1810–1821) set up the Native Institution, a school for training Aborigines, because he saw a useful potential for Aborigines as labourers and mechanics in the lower orders of society (Reynolds 1972: 109). This remained the only attempt by the state to ‘civilise’ the Aborigines in the early nineteenth century. After repeated ‘failures’ the Native Institution closed in 1...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication Page

- Contents

- List of Tables, Maps and Diagrams

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations

- Introduction

- 1. Colonial Domination as a Process of Marginalisation

- 2. The Economic Incorporation of the Dhan-Gadi

- 3. Encapsulation, Involution and the Reconstitution of Social Life

- 4. Creative Bricolage and Cultural Domination

- 5. The Evolution of State Control (1880–1940): Segregated Dirt or Assimilation?

- 6. The New Order: The Aborigines’ Welfare Board

- 7. The Deregulation of a Colonial Being: the Aboriginal as Universal Being

- 8. Racism as Egalitarianism: Changes in Racial Discourse

- 9. The Politics of Identity: from Equal Rights to Land Rights

- Appendices

- References

- Index