eBook - ePub

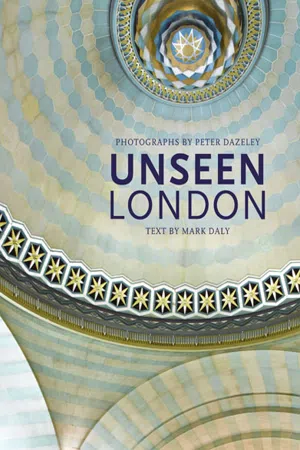

Unseen London

About this book

The original edition of Unseen London.

Peter Dazeley has gained access to the hidden interiors of some of London's most iconic buildings, from Tower Bridge to Battersea Power Station, Big Ben to the Old Bailey.

His photographs of these buildings - some derelict, but many still working - are astonishing. Here is a collection of some 50 extraordinary locations, with a thoughtful text by Mark Daly which tells the story of how each of these places was created, how they are used, and what they reveal about the currents of power flowing through the city.

Unseen London takes you backstage at some of the capital's great theatres, into the changing rooms of some of our greatest temples of sport, into the heart of the Establishment, the boiler room of the city's infrastructure and behind the scenes at some of the most opulent buildings in the Square Mile.

Peter Dazeley has gained access to the hidden interiors of some of London's most iconic buildings, from Tower Bridge to Battersea Power Station, Big Ben to the Old Bailey.

His photographs of these buildings - some derelict, but many still working - are astonishing. Here is a collection of some 50 extraordinary locations, with a thoughtful text by Mark Daly which tells the story of how each of these places was created, how they are used, and what they reveal about the currents of power flowing through the city.

Unseen London takes you backstage at some of the capital's great theatres, into the changing rooms of some of our greatest temples of sport, into the heart of the Establishment, the boiler room of the city's infrastructure and behind the scenes at some of the most opulent buildings in the Square Mile.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Backstage at the dilapidated Alexandra Palace Theatre.

BACKSTAGE

HER MAJESTY’S THEATRE

LONDON PALLADIUM

THEATRE ROYAL, DRURY LANE

BBC TELEVISION CENTRE, WHITE CITY

BBC BROADCASTING HOUSE

DAILY EXPRESS BUILDING, FLEET STREET

ABBEY ROAD STUDIOS

AIR STUDIOS

ALEXANDRA PALACE

HER MAJESTY’S THEATRE

Each performance of The Phantom of the Opera at Her Majesty’s Theatre recreates an impressive subterranean world in its second act. The machinery of that illusion sits alongside the theatre’s own underground secrets. For when The Phantom of the Opera was installed, a condition was set by the planning authority that the special effects systems had to be carefully integrated around the forest of old timbers that comprise the theatre’s unique backstage and understage machinery.

The operational fly floor at Her Majesty’s.

The old wooden-constructed technology at Her Majesty’s is described by the Theatres Trust as ‘the most important survival of its kind recorded in London’. A number of sub-stage bridges, trap doors and the systems to operate them all remain, still in excellent condition. High on the stage left gallery is a ‘thunder run’, a switchback wooden box channel down which a cannonball was once rolled to generate a realistic rumble of thunder. It lies unused, but like the rest of the equipment, could be restored to working order, according to the Trust’s technical survey. Even the stage surface itself is reputed to be the first flat, rather than raked, stage constructed in a British theatre. Drums and shafts above stage and below drive five rising and falling bridges, a downstage ‘grave’ trap, at least four other trap doors and possibly transverse sliders. The wooden grid high above in the rafters carrying four winding drums is elaborately jointed, bolted and plated.

The ‘thunder run’ in the stage left gallery is one of only two remaining in Britain; all the original stage machinery is of wooden construction.

Sub-stage trap with shock-absorbing stack, one of five original traps at Her Majesty’s.

During the nineteenth century London theatre had enthusiastically adopted the machinery of illusion. The 1897 opening enabled Her Majesty’s to be equipped with an array of state-of-the-art stage machinery. The auditorium was electrically lit at the start and the safety fire curtain was powered hydraulically from the mains. The operating cylinder and piston for this remain in place, and are reported to be the only known example still in working order, although the supply of pressurized mains water has long ended. Hydraulic power does not seem to have been applied to the stage machinery as it was at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane.

The building was the last work of leading Victorian theatre architect Charles Phipps, and was conceived at the same time as the Carlton Hotel, now demolished, and backed by the Royal Opera Arcade left from an older building. The interior, by the consulting architect W.H. Romaine-Walker, was inspired by the Opera at the Palace of Versailles. Her Majesty’s is the fourth theatre building on the site and prospered under its extravagant actor-owner-manager, Herbert Beerbohm-Tree, who built the theatre with profits from the successes he had managed at the Haymarket Theatre across the road. At Her Majesty’s he staged sixteen Shakespeare productions, adaptations of Dickens and the first production of George Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion, all before 1914. He also launched an acting school in the dome room of the theatre, which was to form the basis of the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art. The theatre settled on more popular productions in modern times, and it was mostly a string of musical comedies and then Broadway musicals that sustained the theatre.

The auditorium capacity is 1,216, with an interior inspired by the opera house at Versailles, an appropriate environment for The Phantom of the Opera.

Sir Andrew Lloyd Webber’s Really Useful Group has had complete ownership of Her Majesty’s Theatre since 2005, the composer having been with the theatre since 1986, when The Phantom of the Opera opened. At that time some pieces of the wooden stage machinery were temporarily removed for the installation of modern effects. These were carefully tagged and stored for future reinstatement when Phantom vacates Her Majesty’s Theatre. Twenty-eight years later in 2014, with Phantom still playing to full houses, that was proving to be a long wait.

LONDON PALLADIUM

There are forty-one theatres in the two square miles of the West End designated ‘Theatreland’, and the London Palladium is the most northerly and arguably the most famous. Designed in 1910 as ‘the latest thing in musical halls’, the Palladium has always been the embodiment of popular entertainment, with never a whiff of Shakespeare or Sheridan. It was built on the site of a static circus show, and the new auditorium was recognized from the start as a beautiful theatre. It sometimes staged melodramas, farces, pantomimes and operettas, but settled on variety entertainment, the successor to old music hall, as its speciality. In the 1930s it pioneered comedy reviews and added the prefix London to its Palladium Theatre title.

Over more than a century the Palladium has ridden the switchback of theatrical fortune. After the Second World War the Palladium famously got into its stride with a run of productions starring headline Hollywood stars who could sing, dance and entertain, with Frank Sinatra, Bob Hope and Judy Garland topping the bill. While Danny Kaye was a smash hit and Mickey Rooney bombed, British performers resented the emphasis on American stars, but the success of the formula was undisputed. When the draw of the theatre across Britain generally started to fade during the 1950s, the Palladium looked for fresh approaches to popular entertainment. Director Val Parnell saw synergy with the new independent television, and as a consequence the broadcast variety show Sunday Night at the London Palladium ran continuously for twelve years. A straightforward musical theatre production was not staged in the theatre until 1968. Musical spectaculars have since become the Palladium’s trademark.

The Palladium stage is exceptionally deep. The standard of decoration in the auditorium was intended to elevate the music hall to a higher level.

The building has a tangled history. Strictly speaking, it is a rebuild by the leading theatre architect Frank Matcham, a pioneer in the use of the cantilever in steel-frame constructions. No supporting columns are required to carry the balconies, and the sight lines are excellent. The only columns at the Palladium are the Corinthian pillars outside, mounted on tall pedestals at the seven-bay frontage. These were retained by Matcham from the Corinthian Bazaar, the preceding structure, which was a multiple retail space built speculatively by a wine merchant over his cellars in 1868. That enterprise did not succeed. A venue for a fixed circus venture followed, which struggled on into the Edwardian age, with the building along the way housing a skating rink, and staging pantomimes at Christmas. At some point around ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Contents

- Introduction

- Hidden Levers

- Law and Order

- Army and Navy

- Backstage

- Body and Soul

- The Square Mile

- Photographer’s Note

- Dedication

- Acknowledgements

- Copyright

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Unseen London by Mark Daly in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.