![]()

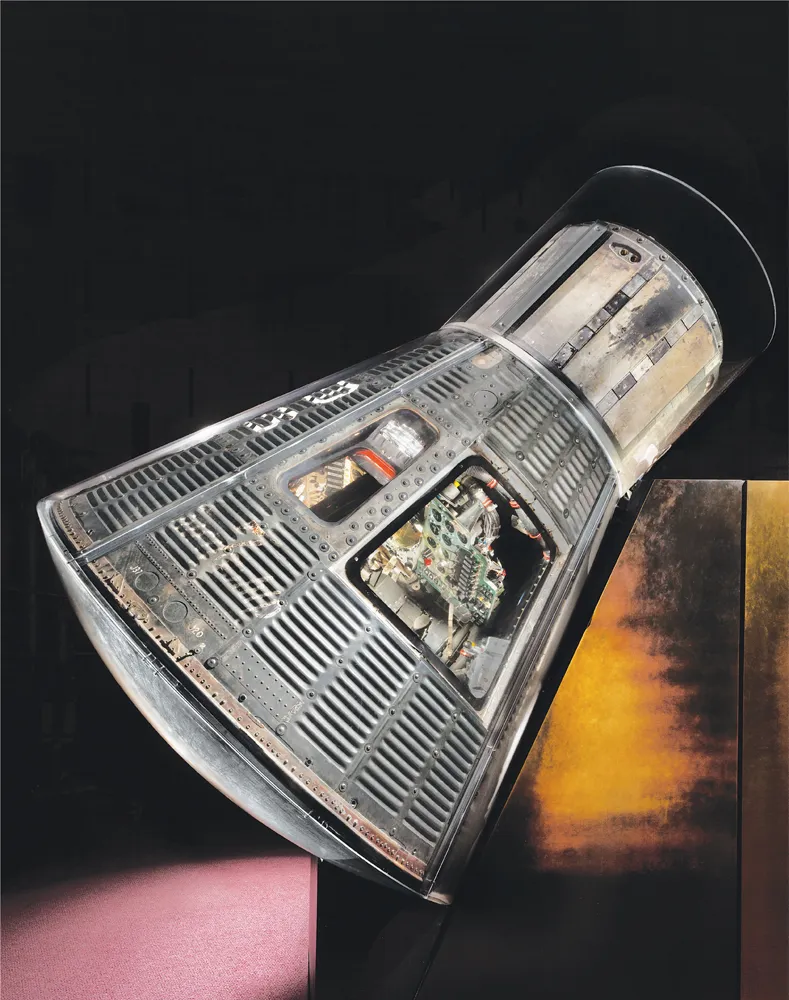

Friendship 7 in the Milestones of Flight gallery at the National Air and Space Museum. NASM

ON FEBRUARY 20, 1962, astronaut John H. Glenn Jr., became the first American to orbit Earth. He made three trips around the world in Friendship 7, a small spacecraft weighing barely more than a ton and a half, which had been hurled into orbit by an Atlas intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM). Glenn was the fifth person in space, following two Soviet cosmonauts who had orbited and two American astronauts who had made suborbital trips of fifteen minutes. Because he was the first to match the Soviet achievement of orbiting, his fame in the United States quickly eclipsed even that of the first American in space, Alan B. Shepard. As a result, Friendship 7 was chosen for the Milestones of Flight gallery at the National Air and Space Museum when it was opened in 1976—not Shepard’s Freedom 7.

Project Mercury, the name given to the initiative to put an American in orbit, had its origin in the immediate aftermath of the Soviet Sputnik surprise of October 4, 1957. The orbiting of a satellite immediately legitimized the Soviet claim of having tested an ICBM—thus making the nuclear threat much more real. Sputnik also hurt American pride as it seemed to demonstrate Soviet scientific and technical superiority, provoking an outcry in the press and in Congress against President Dwight Eisenhower’s administration. When the Soviets sent a dog into orbit in early November, and the first U.S. satellite launching attempt ended in an embarrassing launch pad explosion in early December, it only strengthened the public and scientific outcry. Eisenhower reluctantly conceded to the demands for an accelerated national space program.

This green light only exacerbated the rivalries among the military services, who vied for a place in space, as well as in long-range missile programs. The army and air force started competing plans for launching humans. Annoyed, and advised both by politicians and scientists that a civilian space agency would best represent America’s international image in the Cold War, Eisenhower proposed the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), which was to be built on the foundation of the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA). The president also made the new agency responsible for the first experimental human space program. When NASA came into existence on October 1, 1958, it created Project Mercury to put one man into orbit. At the time, only men were considered for the job that NASA soon dubbed “astronaut”; women pilots who later privately took the astronaut medical exam were rebuffed by the agency.

Pre-Sputnik space advocates imagined that humans would travel to orbit in multiperson spaceplanes. But in a mad dash to beat the Soviets, developing a spaceplane was a luxury the United States could not afford—at least for the first program. The quick-and-dirty approach was to create a ballistic capsule, essentially a missile nosecone big enough to hold a passenger and the systems needed to keep him alive and get him back to Earth. At the NASA Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia, aeronautical engineer Max Faget had already drawn a conical spacecraft with a cylindrical nose. The broad, flat base was covered by a heat shield that would create a shock wave to slow the spacecraft down and ward off the intense heat that would be created by plowing into the Earth’s atmosphere at only slightly less than the orbital speed of 17,500 mph. Protecting the capsule was technology directly derived from ICBM warheads, either heavy metal “heat sinks” or fiberglass and resin “ablative heat shields” that would erode during the reentry. The latter type was used on Friendship 7 and all Mercury orbital missions.

An early publicity shot of the seven Mercury astronauts, probably taken soon after their selection was announced in April 1959. From left to right, sitting: Virgil I. “Gus” Grissom, M. Scott Carpenter, Walter “Deke” Slayton, and L. Gordon Cooper Jr. Standing: Alan B. Shepard Jr., Walter M. Schirra, and John H. Glenn Jr. NASA/NASM

The only big rocket the United States had in 1958 that could launch such a spacecraft was the air force’s Atlas, the nation’s first ICBM. But the Atlas was still early in its development and had an alarming tendency to blow up. Robert Gilruth’s Space Task Group, which was based at the Langley Center and was responsible for Project Mercury, therefore decided that early space missions to test the capsule and train the astronauts were advisable. Adopting an idea from the army’s short-lived human space project, the task group also decided to use that service’s Redstone tactical ballistic missile, which could send the capsule up to a hundred miles in altitude but could achieve only about one-third the velocity needed to reach orbit.

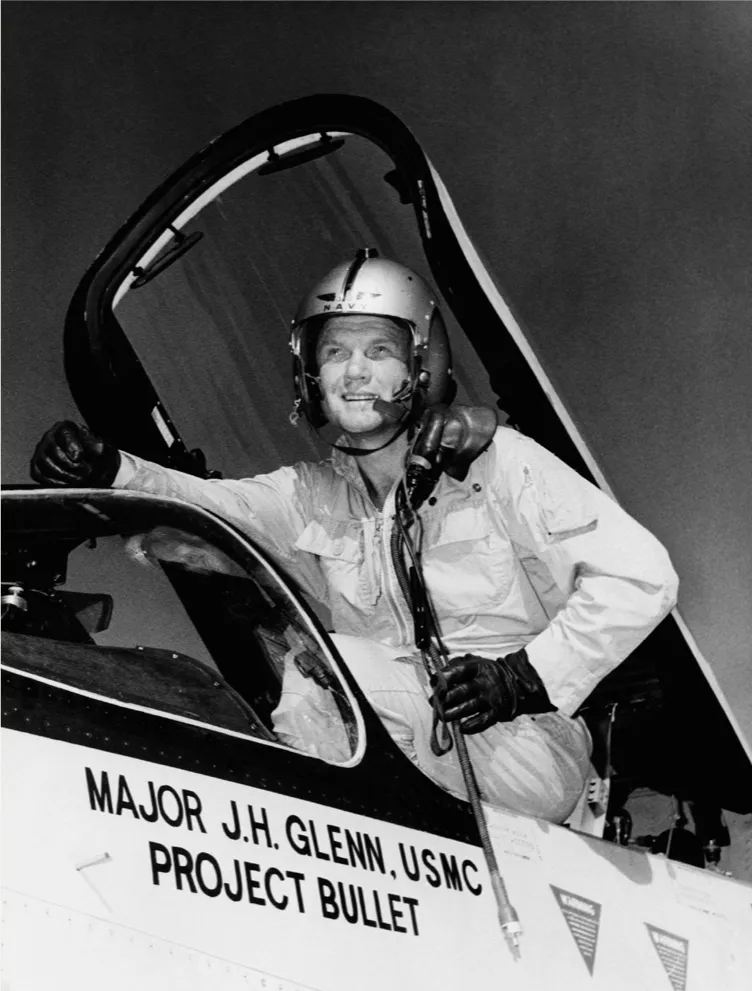

In April 1959, NASA introduced its first seven astronauts who, by presidential order, were chosen from the pool of active military test pilots. Not wanting to be thought of merely as passengers, the astronauts moved quickly to put their stamp on the program. The Mercury capsule was being designed for automatic operation, in large part because the medical effects of spaceflight were unknown. Some doctors imagined that weightlessness and isolation would create physical or psychological problems that would incapacitate the astronaut. Unimpressed by these scenarios of doom, the seven intervened to have a window placed above the pilot’s head and requested various changes to the cockpit layout that would increase control if the automatic systems malfunctioned.

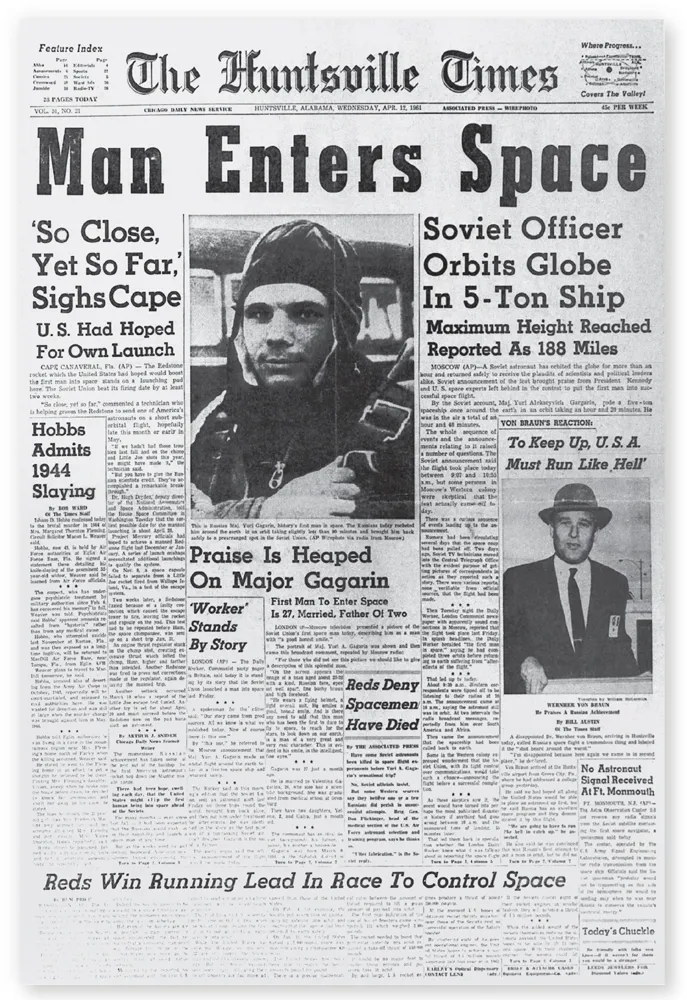

Although the Mercury program proved longer and more complicated than expected, by the end of 1960 the Space Task Group launched the first unmanned Mercury-Redstone suborbital mission, followed by chimpanzee Ham in January 1961 (the doctors required one such live-subject mission before the first human suborbital and orbital flights). While Ham returned safely, any hope that the United States would be first in space was dashed on April 12, when Yuri Gagarin made one orbit around Earth in the Soviet spacecraft Vostok 1. On May 5, Alan Shepard accomplished his suborbital flight, followed in July by Virgil “Gus” Grissom. John Glenn acted as backup astronaut for both. Gherman Titov spent an entire day in orbit in early August. But even without the new Soviet triumph, it was clear to Gilruth’s team that another suborbital test would just delay the orbital flights without producing much new knowledge. It was time to move on—giving Glenn the chance to become the first American in orbit.

The headline in The Huntsville (Alabama) Times after the successful one-orbit flight of Yuri Gagarin on April 12, 1961, shows the impact of the first human spaceflight on world opinion. NASM

Glenn enters Friendship 7 on the morning of the launch, February 20, 1962. Getting into the cramped cockpit was a very tight fit and required the assistance of a couple of technicians. NASA/NASM

The launch of Friendship 7 on the Mercury-Atlas 6 mission. The booster was a modified ICBM. On the top of the spacecraft is the “escape tower.” It has a powerful solid-fuel rocket to yank the capsule away in the case of an emergency. As both the Mercury-Atlas 1 and 3 boosters had exploded in unmanned tests, a successful launch was far from assured. NASA

In September 1961, a capsule made one orbit on the Mercury-Atlas 4 mission, with a “crewman simulator” inside to test the environmental control system. The capsule had been refurbished after its escape system had rescued it from an exploding booster in April, an indication of how dangerous such a flight was for the astronaut. The next mission featured the chimp Enos, who went around the Earth twice in November before the attitude control system used up too much hydrogen peroxide fuel for the control jets, forcing a mission termination before the nominal three-orbit Mercury mission could be completed. Enos’s return to Earth was enough to finally give John Glenn the go-ahead to fly on Mercury-Atlas 6.

Glenn decided to name his spacecraft Friendship 7, following the tradition established by Shepard, who had added the number seven to signify the members of the astronaut team. But technical problems soon pushed the flight into January 1962, which was only the beginning of the mission’s problems. The patience of the press and the public soon wore thin after several more postponements, many due to cloudy winter weather at the launch site: Cape Canaveral, Florida. After the unmanned Mercury-Atlas 1 had exploded in 1959, NASA had instituted a rule that launches must be visible for filming, so that accidents might be more easily investigated.

Finally, on February 20, the weather began to improve. Glenn rose at 2:20 a.m. Eastern time, had breakfast, suited up, and shortly after 6:00 entered the spacecraft. (So tight was the fit that the astronauts joked: “You don’t get into it, you put it on.”) Technicians strapped him into his form-fitting fiberglass co...