This is a test

- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

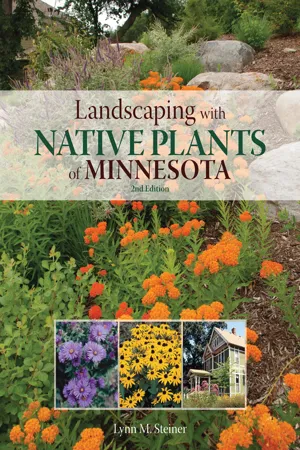

Landscaping with Native Plants of Minnesota - 2nd Edition

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This new and updated edition of Landscaping with Native Plants of Minnesota combines the practicality of a field guide with all the basic information homeowners need to create an effective landscape design. The plant profiles section includes comprehensive descriptions of approximately 150 flowers, trees, shrubs, vines, evergreens, grasses, and ferns that grew in Minnesota before European settlement, as well as complete information on planting, maintenance, and landscape uses for each plant. The book also includes complete information on how to garden successfully in Minnesota's harsh climate and how to install and maintain an attractive, low-maintenance home landscape suitable for any lifestyle.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Landscaping with Native Plants of Minnesota - 2nd Edition by Lynn M. Steiner in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Horticulture. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Understanding

Native Plants

Native Plants

What They Are and How to Use Them

Just what defines a native plant has been debated for many years by many people. A widely accepted definition—and the one used in this book—classifies native plants as those species that grew in an area before European settlement—about the mid-1800s in the Midwest. By and large, Native Americans lived in harmony with the plants and animals of an area without endangering the natural ecosystems. European settlers, on the other hand, had a major impact on the landscape as they cut down large stands of trees, plowed up acres of prairies, suppressed natural fires, and introduced plants from their homelands and other parts of this “new” continent.

Unlike most introduced plants, a native plant fully integrates itself into a biotic community, establishing complex relationships with other local plants and animals. Not only does a native plant depend on the organisms with which it has evolved, but the other organisms also depend on it, creating a true web of life. This natural system of checks and balances ensures that native plants seldom grow out of control in their natural habitats.

“Wildflower” is a commonly used term, but it does not necessarily mean a native plant, since not all wildflowers are native to an area. Wildflowers include introduced plants that have escaped cultivation and grow wild in areas. Examples are Queen Anne’s lace (Daucus carota) and chicory (Chicorium intybus), two common roadside plants, neither of which is native to any area of the United States.

Introducing new plants is not always a bad thing. Where would we be without tomatoes, potatoes, and wheat? And, it’s hard to find fault with introduced plants as charming and well behaved as lilacs and hostas. However, experience has taught us that the introduction of nonnative plants into an ecosystem is a delicate operation that should be undertaken with care. More and more, we are finding that plants that evolved in other countries, or even other areas of this country, can become too comfortable in landscape situations and threaten native flora. A prime example is purple loosestrife, a European native propagated by nurseries and grown in gardens for years before it was realized that it aggressively invades natural wetlands, crowding out native plants. Buckthorn is another European native that has been widely used as a hedge. Today, it is the bane of any homeowner with a wooded plot and it is running rampant through native woodlands.

Classifying Native Plants

Before you can know and effectively use native plants, you must have a simple knowledge of plant taxonomy. The fundamental category in this book is the species, a group of genetically similar plants within a genus, a larger botanical division. Genus and species names are commonly Latin and italicized, with the genus name coming first in capital letters followed by the species in lower case. Learning Latin names can be frustrating, but it is important. Too many plants share the same or similar common names, and it’s easy to end up with the wrong plant—one that may not even be native to your area. Latin names also offer clues on how to identify a plant. For example, knowing that tomentosus means “downy” and laevis means “smooth” will help you identify and remember what a plant looks like.

Within a species, there are also subspecies (abbreviated as “ssp.”) and varieties (“var.”). A subspecies has a characteristic that isn’t quite different enough to make it a separate species. This characteristic may occur over a wide range or in a geographically isolated area.

Varieties have minor recognizable variations from the species, such as flower size or leaf color, but are not distinct enough to be labeled subspecies. An example is found in Cypripedium calceolus (yellow lady’s slipper), which is further differentiated into var. pubescens (large yellow lady’s slipper) and var. parviflorum (small yellow lady’s slipper). The latter plant is shorter and has a slightly different flower shape and color, but without seeing the two side by side, it can be difficult to tell which one you are looking at.

As native plants become more popular, many horticulturally selected cultivated varieties are being introduced. These “cultivars” are usually chosen for certain characteristics such as larger or double flowers, leaf color, compact growth, or flower color, and are propagated by nurseries to maintain the trait. In most cases, these cultivars retain most of the characteristics of the native species and are fine choices for most landscape use. However, if you are doing restoration work, you will want to stick with the species or even the subspecies or variety native to your area to maintain the true genetic diversity you’ll only get from the native species.

For most plants, species is the final classification. However, some plants are divided further into varieties. When you see them side by side, you can see that the Cypripedium calceolus var. pubescens (large yellow lady’s slipper) at left and var. parviflorum (small yellow lady’s-slipper) at right have minor size and color differences, thus the further differentiation into varieties. Some botanists feel that the differences are distinct enough to classify C. pubescens as a separate species.

While the native pink-flowered Physostegia virginiana (obedient plant) is a beautiful flower suitable for naturalizing and prairie plantings, it can be too aggressive for many landscapes. ‘Miss Manners’, a white cultivar, is less aggressive and better suited to garden use.

The term “wildflower” can be a misnomer when referring to native plants as not all plants that grow well in a region are native there. If you see a proliferation of one species—such as the oxeye daisy (Leucanthemum vulgare), a European native—taking over lawns and roadsides, chances are it’s an introduced plant displacing native species.

Many aggressive nonnative plants are introduced as garden plants because they are showy and easy to grow. Campanula rapunculoides (creeping bellflower) is an example of a European native that has become a prolific garden weed. Its thick, tuberlike rhizome makes it difficult to eradicate once it becomes established.

Benefits of Native Plants

There are many reasons to use native plants, some more tangible than others. For many gardeners, the initial attraction comes from native plants’ reputation of being lower maintenance than a manicured lawn and exotic shrubs. For the most part this is true—provided native plants are given landscape situations that match their cultural requirements. Because they have evolved and adapted to their surroundings, native plants tend to be tolerant of tough conditions such as drought and poor soil. Native plants are better adapted to local climatic conditions and better able to resist the effects of native insects and diseases. Their reduced maintenance results in less dependence on fossil fuels and reduced noise pollution from lawn mowers and other types of equipment.

The less tangible—but possibly more important—side of using native plants is the connection you make with nature. Gardening with natives instills an understanding of our natural world—its cycles, changes, and history. Communing with nature has a positive, healing effect on human beings. Learning how to work with instead of against nature will do wonders for your spiritual health.

By observing native plants throughout the year, a gardener gains insight into seasonal rhythms and life cycles. You will experience intellectual rewards that are somehow missing if you only grow petunias or marigolds.

Gardening with native plants will help you create a sense of place rather than just a cookie-cutter landscape. Your yard will be unique among the long line of mown grass and clipped shrubs in your neighborhood. A native-plant landscape will blend into the natural surroundings better that those planted with introduced species, and you will get an enormous sense of satisfaction from helping reestablish what once grew naturally in your area. You will see an increase in wildlife, including birds, butterflies, and pollinating insects, making your garden a livelier place.

On a broader scale, using native plants helps preserve the natural heritage of an area. Genetic diversity promotes the mixing of genes to form new combinations, the key to adaptability and survival of all life. Once a species becomes extinct, it is gone forever, as are its genes and any future contribution that it might have made.

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Contents

- Dedication

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Understanding Native Plants

- Chapter 2 Minnesota’s Natural Plant Life

- Chapter 3 Gardening with Native Plants

- Chapter 4 Landscaping with Native Plants

- Chapter 5 Gallery of Gardens

- Native Plant Profiles

- Bibliography

- Index

- About the Author

- Copyright Page