![]()

CHAPTER ONE

A Brief History of the Cell

The earliest observations of cells were made in the late seventeenth century, but their fundamental importance in the natural world only became apparent over 150 years later, in the middle of the nineteenth century. Since then, increasingly rapid strides have been taken toward understanding what goes on inside cells—and how such processes relate to growth, reproduction, inheritance, disease, and the origin of life on Earth.

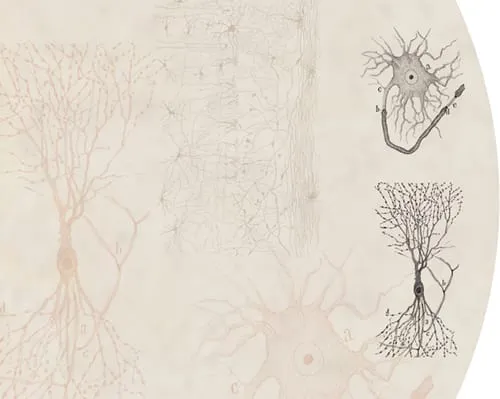

Pioneering Spanish cell biologist Santiago Ramón y Cajal made these remarkable drawings, of interconnected neurons (nerve cells) from the brain of a rabbit, in 1899, just over three decades before the invention of the electron microscope.

A whole new world

When seventeenth-century natural philosophers and physicians gazed through microscopes at plants, animals and fungi they were treated to tantalizing glimpses of anatomy and physiology on tiny scales. Microscopes allowed these scientists and doctors to discover “microorganisms”—entire living things too small to see with the naked eye—and to stumble across the existence of cells.

A revolution in seeing

The facts surrounding the invention of the microscope are about as clear as the images that early examples of these instruments produced. It was in the 1590s, or possibly the early 1600s, and probably in Holland, but possibly in England, that someone first placed two lenses in an arrangement that produced a magnified image. What is known is that the new instrument, more powerful than the hand lenses already in use, quickly captured the imagination of natural philosophers across Europe.

The magnifying power and optical quality of microscopes improved gradually during the seventeenth century. Although minerals and everyday objects were frequent subjects of study, it was closeup views of living things that really caught people’s eyes. In 1660, the Italian physician Marcello Malpighi carried out microscopic studies of human flesh and found tiny blood vessels—the capillaries, which join arteries to veins. The discovery of capillaries confirmed a controversial theory: the circulation of blood, put forward by William Harvey in 1628. Malpighi studied many plants and animals with his microscopes, and in 1666, after studying a blood clot, he described “very small red particles” that “roll and turn helter-skelter”, the first confirmed sighting of what we now call red blood cells.

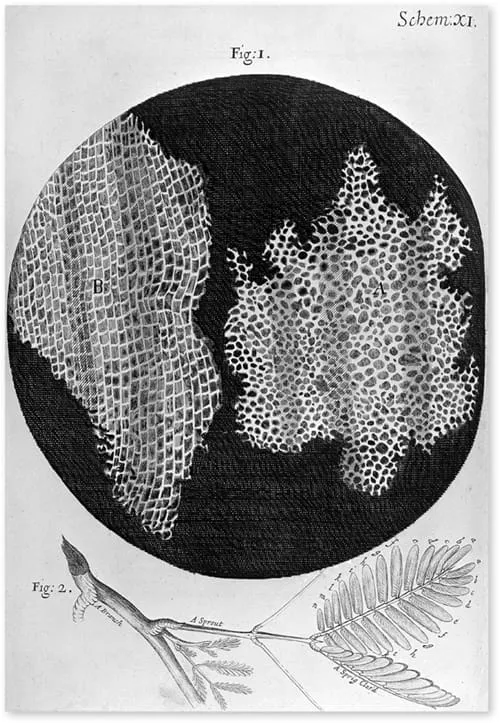

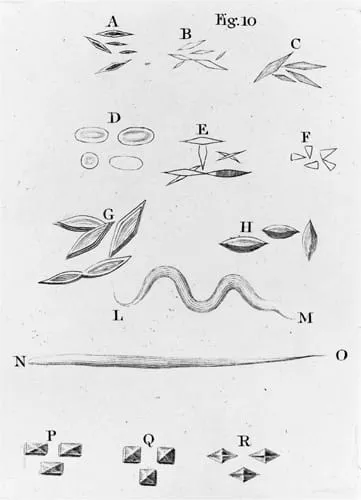

Robert Hooke’s drawing of “cells” in cork. What he actually observed were the spaces enclosed by cell walls of empty, dead cells. Note that “B” is, as Hooke described it, “split the long-ways.”

Tiny boxes

The most influential microscopist of the age was Englishman Robert Hooke. While employed as “curator of experiments” at the new Royal Society in London, Hooke made many observations through microscopes and telescopes, and produced a beautifully illustrated book of what he had seen. Micrographia was published in September 1665 and its exquisite drawings and intriguing text gave readers an insight into a world hidden from everyday eyes. The now famous diarist Samuel Pepys was among those captivated, noting: “Before I went to bed, I sat up till 2 a-clock in my chamber, reading of Mr. Hooke’s Microscopical Observations, the most ingenious book that I ever read in my life.”

It was Hooke who coined the word “cell” to describe what he saw when studying cork. He placed thin slivers of the material onto a dark plate beneath his microscope’s objective lens, illuminated them with light from an oil lamp focused through a thick lens, and gazed through the eyepiece. His description of what he saw, quoted below, is still intriguing.

Hooke estimated that there were about 10,000 cells to the inch (about 4,000 per centimeter) and that one cubic inch would contain about “twelve hundred millions” (about 70 million per cubic centimeter). It was an astonishing discovery; he wrote that this intricate structure was “almost incredible, did not our Microscope assure us of it by ocular demonstration.” Each of Hooke’s “cells” is a cube with sides measuring just over 20 microns, or 0.02 millimeters.

“I could exceeding plainly perceive it to be all perforated and porous, much like a Honey-comb, but that the pores of it were not regular … these pores, or cells, were not very deep, but consisted of a great many little Boxes, separated out of one continued long pore, by certain Diaphragms, as is visible by the Figure B, which represents a sight of those pores split the long-ways.”

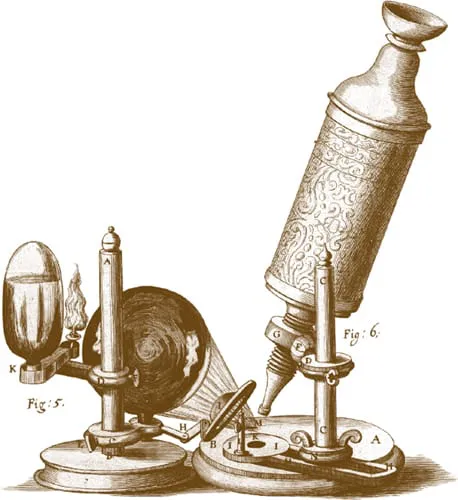

Reconstruction of Robert Hooke’s compound microscope, and its system of illumination, copied from the engraving and description in Micrographia.

Animalcules

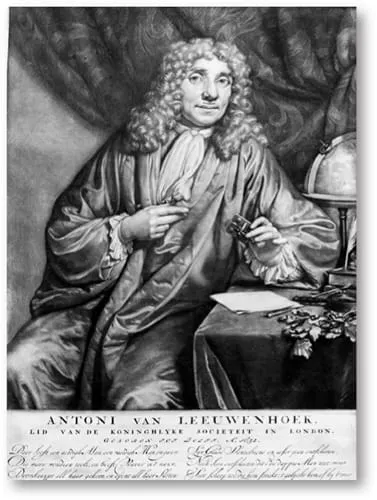

Although compound microscopes (with two or more lenses) were popular during the seventeenth century, many investigators also used “simple microscopes”—just single powerful lenses. Some of these could magnify as well, if not better, than their more complicated counterparts. One man who favored single lenses was Antony van Leeuwenhoek, a successful Dutch draper. Leeuwenhoek made tiny, near-spherical lenses by melting glass rods in a flame. He carefully ground them to the right shape and attached them to ingenious handheld metal frames that also held the specimen. He investigated everything from tongues to sand and became the first person to describe sperm cells (which he found in the males of several species, including humans). While most microscopes of the time achieved magnifications of between 30x and 60x, Leeuwenhoek’s could magnify more than 250x.

In 1675, Leeuwenhoek observed tiny living creatures in a sample of rainwater that had been standing for a few days. These microorganisms were far, far smaller than any living things anyone had ever seen. Leeuwenhoek called them “animalcules.” For the next year he studied river water, well water, and seawater, some of which he left standing for several days or weeks. Mostly, he saw protozoa and single-celled algae, which are about the same size as Hooke’s cork cells—some quite a lot larger. But in April 1676 he saw animalcules that were much smaller, and these he described as being so tiny that you would need to lay more than a hundred end to end to measure the same as a grain of sand. This was almost certainly the first observation of bacteria.

A letter that Leeuwenhoek wrote in 1683 contains the world’s first illustrations of bacteria. The letter detailed his microscopic investigations of his own dental plaque: “I have mixed it with clean rain water, in which there were no animalcules, and I saw with great wonder that there were many very little animalcules, very prettily a-moving.” Leeuwenhoek also wrote that “there are not living in our United Netherlands so many people as I carry living animals in my mouth this very day.”

Leeuwenhoek (see here) was prolific; he made more than 500 microscopes and wrote hundreds of letters informing scientific societies about his discoveries—including 190 or so to the Royal Society in London. The drawings (see here) are taken from one of his letters. Leeuwenhoek’s microscope (see here) was a handheld metal frame with screws to adjust the stage (sample holder) and to move the lens for focusing.

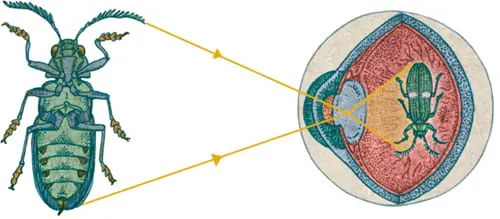

1 NORMAL VISION

2 WITH MAGNIFYING GLAS...