![]()

1. Appalachian Migration

Setting the Musical Stage

in Southwestern Ohio

PHILLIP J. OBERMI LLER

INTERNAL MIGRATION REMAINS a hallmark of twentieth-century America. Farm families impoverished by Dust Bowl droughts sought agricultural work in California’s Central Valley. The imposition of Jim Crow laws and the boll weevil infestation in the cotton-growing South forced many Black families to seek employment in the nation’s cities. High birth rates and changes in the economics of both agriculture and the extractive industries impelled migration from Southern Appalachia to many of those same cities.

These population movements included men, women, and children, swelling the migration streams to hundreds of thousands of people. They included the poor, blue-collar workers, and many middle-class folks as well. Nearly everyone in small-town and rural America was affected by these conditions. In every case the migrants took their music with them: western swing found its way to California, while jazz and bluegrass flourished in the destination cities of Southern Black and Appalachian migrants respectively.

Appalachian Migration

Migration underpins the spread of bluegrass music throughout southwestern Ohio. People have been moving into and out of what became known as the Appalachian region for centuries. Streams of migrants began to flow out of the Southern mountains after World War I, but these were mere trickles compared to what came later. The flood of out-migrants that occurred between 1940 and 1970 would be part of what became known as the Great Migration.

The downturn in the Appalachian regional economy had begun as early as the 1920s, affecting farmers in eastern Tennessee, timber workers in western North Carolina, and coal miners in eastern Kentucky and West Virginia. Among the first to leave were African Americans and European immigrants who had been attracted to the coalfields by opportunities for work and wages but had few strong ties to the region.

Early on, some Appalachians were seasonal farmworkers who worked the onion crops in Ohio or the tomato crops in Indiana, returning home after the harvest. This back-and-forth movement is known as shuttle migration. Maintaining a homestead in the region, shuttle migrants became temporary laborers akin to the migrant farmworkers of today, although this type of migration involved both agricultural and industrial workers. During the Depression, for instance, Detroit autoworkers worked only a few months each year until the corporate quota for expected new car demand was met. For the most part, Appalachian workers returned to their home places in the mountains until they were called back to field or factory. The Depression era only increased shuttle migration. In 2004 I described typical shuttle routes:

The first surfaced highways in the mountains brought bus lines into the Appalachian region in the late 1920s. The road-building programs of the Roosevelt administration came into the mountains in the late 1930s; north-south arteries such as Routes 23, 25, and 27 and east-west corridors such as Routes 50 and 52 made the mountains and many outlying cities accessible to each other. Although these roads were ostensibly built for commerce, they began to be used heavily by individual commuters as routes out of the mountains. An oft-repeated mountain maxim prescribes a knowledge of “readin’, writin’, and Route 23” as key elements for success. This bit of popular wisdom promoted the paradox that the only way to survive in the mountains was to leave them.

World War II drew thousands of women and men out of the mountains into the military and the war industries. The Wright Aeronautical plant in southwestern Ohio, for example, encompassed thirty-seven acres under one roof. At its peak it employed twenty thousand workers, many of them Appalachian migrants, who turned out a total of sixty thousand military aircraft engines. Today it is the site of General Electric Evendale.

Following the war, the economic bottom dropped out in the Appalachian coalfields as diesel fuel replaced coal for marine and railroad engines, oil and natural gas replaced coal for home heating, electricity replaced coal in the steel industry, and mechanization replaced miners across the board. At the same time, factories in and near cities outside the region were booming. The Great Migration involving millions of Appalachians began in earnest.

These migration streams brought hundreds of thousands of Appalachians to the Midwest. The migrants frequently started out in port-of-entry neighborhoods such as Fifth and Wayne in Dayton, Over-the-Rhine in Cincinnati, Uptown in Chicago, or the Briggs neighborhood in Detroit. Some migrant families became trapped in a cycle of poverty that still affects them several generations later. Most, however, did not stay in the city centers for long, because their jobs were often in suburban or exurban locations. In southwestern Ohio, industrial work was plentiful at Armco, the Delco and Frigidaire Divisions of General Motors, Ford, Formica, Nutone, National Cash Register, U.S. Shoe, and Champion Paper.

The draw of Champion Paper provides a good example of why, at least in some counties of eastern Kentucky, a suitcase was commonly called a “Hamilton”:

Migrants from Kentucky were arriving in Hamilton, Ohio, as early as 1900 to take jobs at Champion Paper and other area industries. Hamilton companies actively recruited the migrants because of their mechanical skills. Local newspaper editor James Blount notes: “Some of the other industries here … figured that Champion was drawing enough people that they would get some of the spillover. … Mosler [Safe] might pick them up or some other factory.” The Hamilton Evening Journal reported that 138 families arrived from Kentucky seeking jobs in one two-week period in 1924. “Kentuckians took Ohio without firing a shot,” one Appalachian migrant recalled in a 1983 Journal feature on Appalachian origins.

Regular industrial wages gave Southern migrants the wherewithal to enjoy their musical heritage through the purchase of instruments, records, phonographs, and radios, along with listening to jukeboxes, attending live concerts, or enjoying both live and recorded music in local churches, clubs, pubs, and restaurants. Referencing the “father of bluegrass,” Bill Monroe, historian Chad Berry writes, “Monroe’s new music—bluegrass, according to the film High Lonesome—a blend of sacred and secular, urban and rural, hill and ragtime, sentimental and blue, may have been born in the South, but it was nurtured in the North.”

Migration Flows

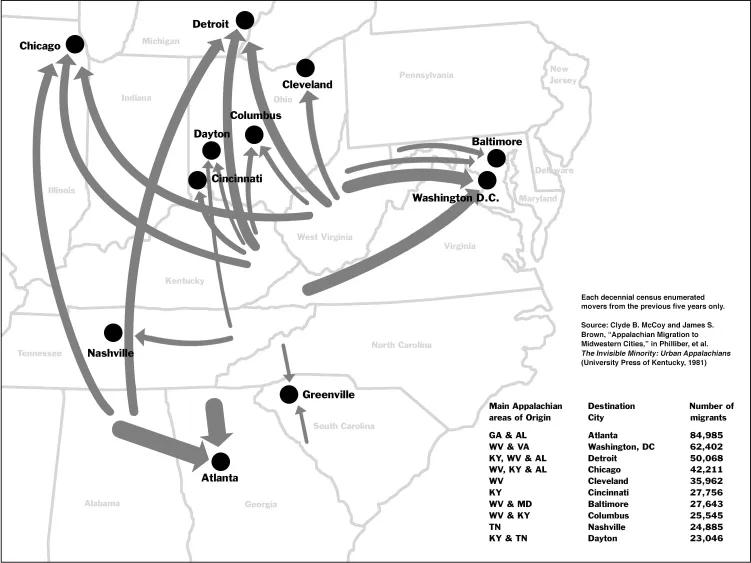

Appalachian migration flows in the 1950s and ’60s were one of the largest internal migrations in our nation’s history (map 1). We should imagine arrowheads at both ends of migration streams, because shuttle migration typified, at least initially, people’s movements to and from the mountains. Relocation to the city was often accompanied by frequent, sometimes weekly, visits back home. The energy crisis of the 1970s put a premium on coal production and drew many migrants back to the coalfields. By the 1980s, however, the outward flows began again and have not changed direction since.

Some migrants, however, moved back to the mountains. This could be due to a family breakup where one or both spouses couldn’t abide city life, for economic reasons, or simply a preference for life as they had experienced it “down home.”

MAP 1. Migration Flows from Appalachia to Selected Cities, 1955–1960 and 1965–1970

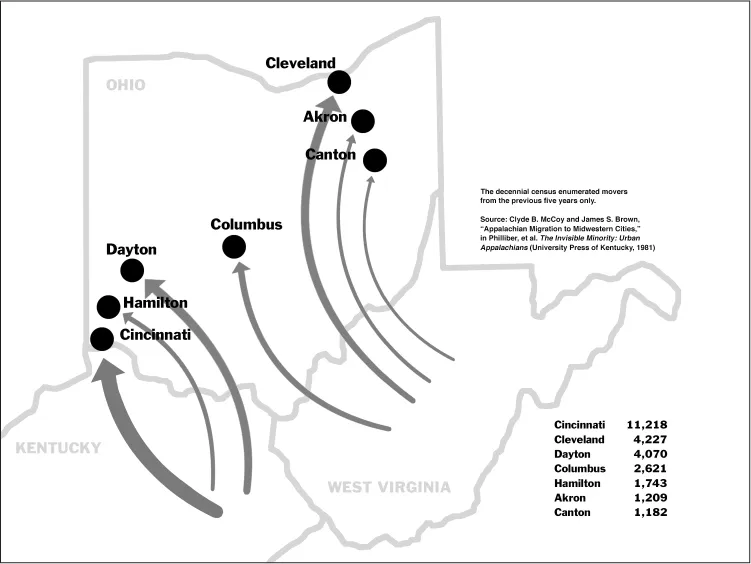

Now imagine arrows running between some of the cities (map 2). Cincinnati, for example, was a major Midwestern transportation node for Appalachians on the move. The city was often a waypoint for migration to Hamilton, Dayton, Detroit, or Chicago. Folks would check in with relatives or friends to test the local job market before moving on.

This pattern of movement between and among points of origin and destinations is described as the “stem and branch” system. With a family base in the mountains and support groups along the way, people prospecting for work could branch out and seek new opportunities. The stem and branch system provided a means of communication and a safety net that reduced risk. Money also flowed through this system as those who found work sent remittances to kinfolk to enable their migration or to help support those remaining back home.

Map 3 shows the relative size of the destination city rather than the absolute number of Appalachians, but the gravity theory of migration is pretty clearly demonstrated, where larger populations have more opportunities that attract more migrants.

MAP 2. Migration Flows from Appalachia to Selected Cities in Ohio, 1965–1970

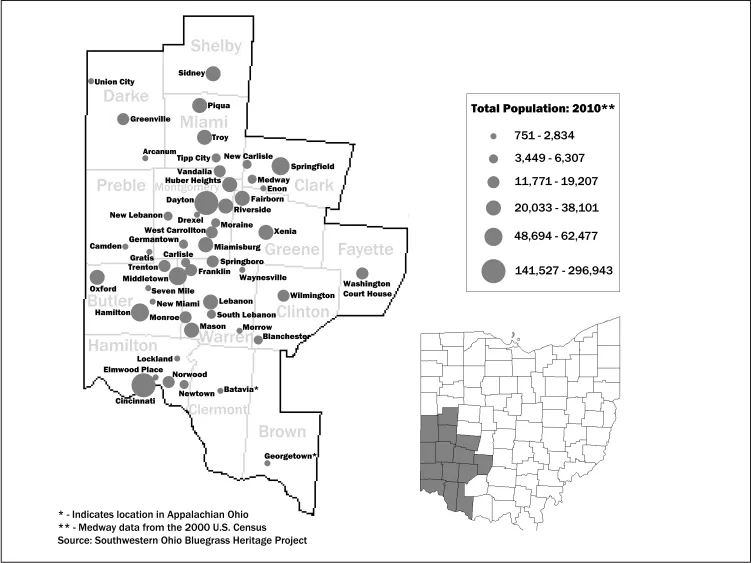

Once they got their feet on the ground, most migrants moved to the suburbs, exurbs, and small towns near major cities, as commuting to work became an option. They also started a variety of civic and social groups in southwestern Ohio, including Cincinnati’s Appalachian Community Development Association and the Urban Appalachian Council (or UAC, now the Urban Appalachian Community Coalition), Dayton’s Our Common Heritage, and Hamilton’s O’Tucks (Ohioans from Kentucky). These groups celebrated Appalachian arts and crafts, foodways, and musical heritage through the Appalachian Festival in Cincinnati, Mountain Days in Dayton, and annual events in Hamilton.

Housing played almost as important a part as job availability in determining migrant destinations. Affordable housing within reasonable driving distance of worksites allowed migrants to disperse widely across southwestern Ohio. Many migrants had moved from place to place in the coalfields, following available work, and home ownership would have hindered that flexibility. Likewise, in the cities, renting was preferred until a stable occupation and income made buying a house, however modest, feasible. Making such a purchase indicated a commitment to the new location, a difficult decision for many, but one that more often than not turned mountain migrants into urban Appalachians.

MAP 3. Selected Towns and Cities in Southwestern Ohio with High Numbers of Appalachian Residents

Movement along the stem and branch system evolved from an economic survival strategy to take on a personal aspect as well:

In later years, however, returns home took on social dimensions beyond the purely pragmatic aspect of having a refuge in hard times. Visits home became a form of cultural refreshment and social renewal apart from the rigors of city life. In the words of Louisville Courier-Journal reporter Ora Spaid: “They find the big cities cold, impersonal, and unwelcoming. So they come back home. Not necessarily to stay, but to be emotionally restored in the warmer, friendlier surrounding of people who care.”

Migrants and Music

The individual experience of migration is hidden within data about large migration flows. Personal accounts provide a sense of who the migrants were and the key role that music played in their lives.

Ron Eller, a first-generation migrant, became a nationally recognized historian at the University of Kentucky. He is emblematic of thousands of migrants who achieved a secure middle-class life. Eller devoted his career to understanding the history of the region and examining the structural causes of its economic difficulties: “My people, of course, were hillbillies, and we had just moved from West Virginia to Ohio. Along with 3.5 million other Appalachians who migrated to the industrial cities of the Midwest after World War II, we were often received with suspicion and frequently cautioned to speak correctly, dress properly, and listen to the right kind of music.”

Mike Maloney is a first-generation migrant from Breathitt County, Kentucky. Coming from a large extended family, he was vitally aware that migration was not succes...