![]()

Part I:

THE BIG PICTURE

dp n="12" folio="11" ? The floating market in Bangkok

dp n="13" folio="12" ? ![]()

1

Feeding Our Cities

In towns and cities across the globe, in large ways and small, urban farming is quietly gaining momentum. If you’re slurping a bowl of hot tom yam goong from a street vendor in Bangkok, enjoying a traditional potato omelet (chips mayai) in Dar-es-Salaam, sipping a glass of merlot in Santiago, or indulging in honey-and-goatcheese ice cream at the Fairmont Waterfront Hotel in Vancouver, chances are you are supporting urban farming. Modern urban farming is closely connected with urbanization, and increasingly with a conscious move toward sustainability. It has even become an unexpected necessity in some places, such as Havana (pictured).

The human population of the world is rising by about 75 million people per year—mostly in cities—and is expected to exceed 9 billion by 2050. Sure enough, some of the growth in urban farming happens when towns grow into cities, and cities into megacities, sprawling into once-rural land. Instead of displaced rural farmers working the newly urban landscape, researchers have found most urban farmers to be established city dwellers. It is usually driven in the global north by those looking to reconnect with a sense of place and to live more sustainably, and in the global south by those just looking to live.

dp n="14" folio="13" ? dp n="15" folio="14" ?Across the United States, communities are taking steps to create a more welcoming atmosphere for agriculture through farmers’ markets, zoning-law changes, and use of underused green spaces and brownfields (former industrial sites), often through the irrepressible efforts of a few individuals with a passion to make it happen. One such example is the Goat Justice League in Seattle, which is fighting to legalize goats within the city limits and has succeeded with pygmy goats so far. But is farming in the city even realistic? The short answer is yes.

About 15 percent of the world’s food supply is already produced in and around cities. Many individual countries and cities are even more advanced. Shanghai (pictured), for example, produces more than 50 percent of its consumed chicken and pork, 90 percent of its eggs, all of its milk, and more than 2 million tons of wheat and rice in and around the city. And Shanghai is no shrinking-violet, backwater city—it has roughly 20 million residents and more than four times as many skyscrapers as Manhattan.

Even as urban agriculture has taken root in cities around the world, traditional rural agriculture—at least the Currier & Ives vision of it—has evolved into something more Dickensian. The changes in farming over the past three centuries have brought extraordinary productivity, both enabling and enabled by growing cities. However, only recently has the true cost of these gains emerged. At its worst, this “industrial agriculture” is antithetical to our heritage, as discussed in the next section, and a threat to our future.

dp n="16" folio="15" ?

Roots of Urban Farming

In March 2009, in the midst of a recession and two wars, First Lady Michelle Obama helped break ground on a new vegetable garden at the White House—the first since her predecessor Eleanor Roosevelt planted a “victory garden” in the midst of World War II. Mrs. Roosevelt’s garden had itself hearkened back to the work-relief gardens of the Great Depression. Before that came the Federal War Garden program of World War I as well as Detroit’s “potato patches” and other responses to the 1893 depression. Urban dwellers have turned to gardens countless times throughout history to weather adversity and regain a sense of autonomy.

dp n="17" folio="16" ? First Lady Michelle Obama in the new White House vegetable garden.

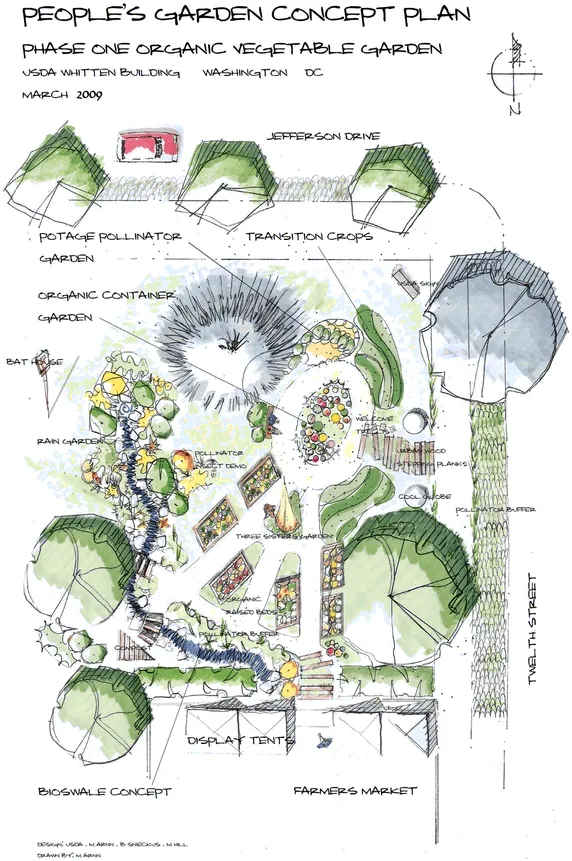

The White House is not alone. Since 2009, statehouses and municipal governments from Baltimore to Sacramento have begun their own food gardens. The United States Secretary of Agriculture opened a “People’s Garden” at its headquarters and encouraged similar efforts at its facilities around the country. Seed sales jumped by about 25 percent, and about 40 percent more households grew vegetables that year than two years earlier.

Across the Atlantic, similar efforts are afoot. In June 2009, Queen Elizabeth unveiled a vegetable patch on the grounds of Buckingham Palace, the first (once again) since World War II. The waiting list in London for allotments—patches of land rented out to gardening-minded residents at a nominal cost—can stretch into decades, and the supply of allotments in the United Kingdom is reportedly short about 200,000 units—in a country with one-fifth the US population. London hopes to create 2,012 new urban agricultural spaces by 2012—in time to feed visiting Olympians with local food. New construction throughout the European Union may soon include integrated “vertical allotments” in accord with regulations being considered by the European Environment Agency. These allotments could include balconies, rooftops, and walls earmarked for growing food on high-rise buildings.

Why is urban farming integrated into cities such as Shanghai but still a novelty in the United States? Certainly, part of the reason is that we have profited so abundantly from the transformation from traditional farming into industrial agriculture—yields per farmer have skyrocketed. This success has reinforced the notion that city is city and country is country, and never the twain shall meet—except in supermarket aisles. It is a bias evidenced, perhaps, by the fact that goats in Seattle may be more striking to us than a world population ballooning beyond the ability of conventional agriculture to feed it. Yet this separation of urban and farming is a modern one.

dp n="18" folio="17" ? dp n="19" folio="18" ? The perennial fascination with the Hanging Gardens of Babylon speaks to the enduring allure of urban agriculture.

The histories of cities and agriculture are, in fact, inextricably linked. Historians may bicker about whether the discovery of agriculture encouraged our ancestors to settle down into permanent settlements, or whether the first settlers developed agriculture out of necessity, but the correlation between the two is clear. Some of the plants and animals first domesticated were cultivated in the rich soil of ancient Fertile Crescent cities such as Jericho (West Bank), Damascus (Syria), Susa (Iran), Tyre (Lebanon), and Catal Huyuk (Turkey).

Egypt and the citystates of Mesopotamia had developed advanced, irrigated agricultural techniques by 6,000 BC, some possibly employed in the legendary “Hanging Gardens of Babylon” (which might have actually been in Nineveh or Nimrud; all three cities are in modern-day Iraq). These Near Eastern civilizations also dabbled in aquaculture—the farming of seafood—as did ancient China, which continues the practice on a large scale. In fact, China has long practiced advanced agricultural techniques to feed its many towns and cities, maintaining a stronger connection to urban farming than most places in the world. Then, as now, China also employed an “aqua-terra” system of wetland farming, which was familiar to ancient Indonesia, as well.

One of the most famous historical examples of urban farming occurred in and around Tenochtitlan, the Aztec capital that is now Mexico City. On shallow lake bottoms, the Aztecs built chinampas, which were essentially raised beds fenced in with woven canes—almost giant baskets—filled in with river mud and organic matter to above the water level. Aztec farmers traveled in between rows of chinampas by boat. Hundreds of miles south and thousands of feet higher, the Incas built farming terraces into mountains and their cities, such as Machu Picchu. The Mayans practiced urban agriculture extensively, as well.

When Rome finally defeated its nemesis city-state Carthage (in modern Tunisia) in 146 BC, legend has it that the Romans plowed salt (a plant killer) into the ground so that nothing would grow there, essentially erasing a city by destroying its agricultural base (well, by that and by killing or enslaving the entire population and reducing the city to ashes). It’s improbable that the Romans would actually sprinkle the fields with salt—it was an expensive commodity—but the legend points to an appreciation of urban farming.

Unfortunately for Rome, this appreciation didn’t translate into action. In a funny twist of fate, the Roman politician keenest to have Carthage destroyed, Marcus Porcius Cato, also had a major beef with lazy Romans who “prefer to exercise their hands in the theatre and the circus rather than in the corn field and the vineyard.” They may have followed his advice in destroying Carthage, but they completely ignored his enthusiasm for farming. As a result, Rome’s population growth, soil depletion, and reliance on imported food contributed to its own downfall six centuries later.

The rises and falls of great cities—and civilizations—have long been intimately tied to agriculture. (And as Rome discovered, sometimes karma really is a boomerang.)

dp n="21" folio="20" ?

So What Happened to Urban Agriculture?

The long decline of urban agriculture coincided with technological advances of the Industrial Revolution (or Revolutions, according to some), which brought with them a change in perception about the roles of cities, rural communities, and agriculture. A passage from historian Will Durant is revealing, written roughly halfway between the post-Civil War flowering of the Industrial Revolution in the United States and today:

The first form of culture is agriculture. It is when man settles down to till the soil and lay up provisions for the uncertain future that he finds time and reason to be civilized. Within that little circle of security—a reliable supply of water and food—he builds his huts, his temples, and his schools; he invents productive tools, and domesticates the dog, the ass, the pig, at last himself. He learns to work with regularity and order, maintains a longer tenure of life, and transmits more completely than before the mental and moral heritage of his race.… Culture suggests agriculture, but civilization suggests the city.

Durant manages two great insights here, one intentional and one not. His understanding of the connection between agriculture and cities reflects an ancient sensibility, yet he also reveals a modern industrial bias that views cities as the zenith of civilization—one that excludes agriculture, or at least pushes it to the rural fringes. It is a tendency to view the city as something that has transcended agriculture, a concept that civilization may have sprouted in the field but only blooms in the boardroom.

This attitude pervades our culture, even in the very sciences responsible for feeding people. Noting that very little agricultural research concerns urban agriculture, Gordon Prain, the global coordinator of Urban Harvest (an initiative of the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research [CGIAR]), writes that the disparity “is related to the sectoral separation of ‘urban’ and ‘rural,’ a separation that has its roots in the Industrial Revolution and its subsequent transfer through colonial expansion to the developing world.”

dp n="22" folio="21" ?The Industrial Revolution was punctuated by a flurry of world-changing inventions and discoveries within a relatively short period, among them the steam engine, the Bessemer process for making steel, the rediscovery of concrete, pasteurization, and all kinds of machines. In the United Kingdom, its epicenter, the Industrial Revolution went hand-in-hand with a series of “Inclosure Acts.” These laws divided up “the commons” (lands everyone could share for farming, pasturing livestock, gathering wood, and other purposes). New farming methods required large fields, which the authorities created by consolidating the commons’ traditional crazy quilt of small plots and fencing them off. By eliminating traditional rights to share the land, the laws had the effect of taking away the livelihood of rural peasants (“commoners”), who comprised the majority of farmers.

No longer able to survive in the country, displaced peasants flooded into cities to feed the new craze: making stuff. As a result, rural food production and urban manufacturing in mills and factories both exploded. The mass production of goods—edible and otherwise—of the new era coincided with mass consumption made possible by colonial expansion, booming population growth, and improvements in transportation. The Industrial Revolution also oiled the economic machine, providing a world stage for corporations and trade unions, which entered stage right and stage left, respectively.

Industrialization prompted the divorce of urban and rural, with rural getting sole custody of agriculture—an arrangement that remains the status quo. As discussed next, however, this rigid distinction has outlived its usefulness, and the results are ever more disastrous.

The New Business of Agriculture

The tectonic agricultural shifts of the Industrial Revolution reached earthquake intensity in the latter half of the twentieth century. In particular, a “Green Revolution” began after World War II, prompted by peace and a desire to feed a growing world, and enabled by new high-yielding crop varieties, irrigation techniques, and synthetic pesticides and fertilizers—starting with a postwar American surplus of ammonium nitrate, an ingredient in explosives. Cheap oil and water fueled the revolution. In the United States, the practice of farming evolved into “agribusiness” thanks to economies of scale, government subsidies, and an official bias best captured by the mandate of Earl Butz, Secretary of Agriculture under Presidents Nixon and Ford: “Get big or get out.”

And so farmers did. Mary Hendrickson and William Heffernan of the University of Missouri have tracked this consolidation in terms of the concentration ratio, or how much of the total market the top firms in each industry control. In a 2007 study, the top four players in beef packing, for example, control 83.5 percent of the market, and the top four companies in pork packing control an estimated 66 percent. In flour milling, the top three companies control 55 percent of the market. And we’re not talking about eleven different firms. We’re talking about seven, since some companies dominate in more than one industry. Cargill, for example, is a leader in all three categories.

At its worst, this concentration in agribusiness has resulted in industrial agriculture, of which the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS) outlines four main characteristics: monoculture, few crop varieties, reliance on chemical and other inputs, and separation of animal and plant agriculture.

Monoculture

Monoculture is the cultivation of a single kind of crop in a given area. Our current agricultural system has immense swaths of monoculture, including our “amber waves of grain.” Among the principal crops tracked by the National Agricultural Statistics Service, for example—mainly grains, legumes,...