This is a test

- 96 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

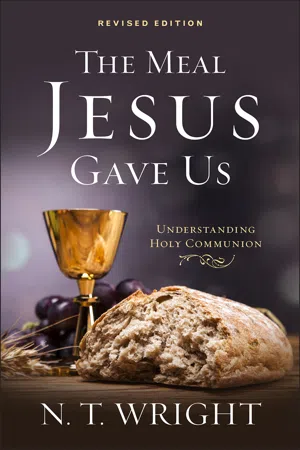

The Meal Jesus Gave Us, Revised Edition

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

In this introductory volume, perfect for Protestant new member and confirmation classes, acclaimed theologian and writer N. T. Wright explains in clear and vivid style the background of the Last Supper, the ways in which Christians have interpreted this event over the centuries, and what it all means for us today. This revision includes questions for discussion or reflection after each chapter.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Meal Jesus Gave Us, Revised Edition by N. T. Wright in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theologie & Religion & Christliche Rituale & Praktiken. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Theologie & ReligionSubtopic

Christliche Rituale & PraktikenPart One

HOW IT ALL BEGAN

1

The birthday party

You are just sitting down to the table. It is your ten-year-old sister’s birthday party. (If you’re too old to have a ten-year-old sister, think of your daughter, your niece or your granddaughter.) Everything is ready: the table is laid; the birthday cake is waiting to have its candles lit. There are balloons everywhere. People have come with odd-shaped parcels.

Everyone has arrived; but suddenly the doorbell rings. You rush to see who it is. There, just arrived from his own planet, is a polite (and fortunately English-speaking) Martian. He asks graciously if he can come in. This is going to be a birthday party with a difference. You bring him into the house, and to the room where the party is about to start. After the shock and surprise, people realize he’s harmless and just wants to enjoy the fun. The party gets under way.

But the Martian, who feels he knows you best since you met him at the door, keeps asking you in a low voice what’s going on. Why are all these people here? Why do they pull those things that make a bang? Why are they wearing funny hats? Why does the little girl in the middle of it all keep opening parcels? And why, oh why is someone trying to set fire to that cake?

Every time you try to answer him, it seems to make him more puzzled.

‘It’s her birthday!’

‘You mean she’s just been born?’

‘No – she was born ten years ago!’

‘So what’s special about that?’

‘We always do this each year.’

‘What’s a year?’

‘It’s when … well, you know, 365 days.’

‘It isn’t with us … but never mind. Why are they giving her things?’

‘Because it’s her birthday.’

‘Why do you give people things on their birthday?’

‘Because we always do … I guess – I suppose – I guess it’s to tell them we think they’re special.’

‘Isn’t everybody special?’

‘Well, yes … but on your birthday you’re extra special.’

‘So why are you wearing those funny hats? Are they special too?’

‘Well, yes, in a way … they’re to make the day different.’

‘And why are they setting fire to the cake?’

‘They aren’t – those are candles.’

‘But why are you lighting candles? It’s quite light in this room – I can see you perfectly well.’

‘We always do … I guess it’s because it makes the party special again.’

‘But why do you put them on the cake?’

‘I dunno. We just always do. Everybody does.’

‘We don’t … but never mind. Why do you all eat things to celebrate someone’s birthday?’

‘Now there you’ve got me. I don’t know. But who cares? Here, shut up a minute and have some cake …’

Imagine life without parties. Imagine life without the thousand things we do, large and small, that give shape to who we are, that give extra meaning and value to people, to occasions, to the way we do things. I guess you can just about imagine living without any little outward signs as to what you were thinking – no hugs and kisses at the start and end of the day, no wave of the hand, no handshakes, no raising of a glass to toast a bride, or a colleague, or an exam passed. I suppose we might, if we tried very hard, be able to organize our lives without special meals on special occasions, without special trips to special places, without all those things that bring colour and depth to our world. We might just manage it. But life would be very dull.

All human societies, in fact, have developed ways of saying things by doing things. Or, if you like, of meaning things by doing things. A military salute, a pat on the head, the handshake that clinches a business deal: all these are symbolic actions that say things, that mean what they mean within a particular world. And some of the most meaningful things are the special meals that people share together. A wedding reception. The supper when the teenager comes home after six months on the other side of the world. The surprise party to celebrate the end of exams. And, of course, the birthday party.

The birthday party says two things in particular. ‘Jane, we wish you a very happy birthday today; and we’re glad that, ten years ago, today, you made your grand appearance into the world.’ The party joins together the past event and the present moment. (When my children were little, we used to tell a suitably abbreviated version of the story of the day they were born as part of the party entertainment.) It also looks into the future: ‘Many happy returns of the day!’ we say, even to a ninety-two-year-old. Somehow past, present and future are held together in this one meal. That’s why we make it special, with things that are both silly and meaningless at one level (party hats, candles, and so on) and very special and meaningful at another level (they show that this isn’t just an ordinary meal, and that while we’re enjoying it we aren’t just ordinary people, either).

Why do we do all this? Different traditions grow up in different countries, but there seems to be a universal desire to make things special. It’s built into us. It’s just the way we are. It goes back to some of the oldest stories about the human race: about people who know in their bones that they are made for each other, made to celebrate the good things of life, and made to do all this to the glory of their maker. The person who wrote the book of Genesis would not have needed to ask, like our Martian friend, why we were having a birthday party. It would have made a whole lot of sense.

Now come to a different home. This time you can be the Martian, and tiptoe into a different party.

* * *

For discussion or reflection

Which occasions in your life – past or future – would you say are especially worth celebrating with others?

Are there any special or unusual customs you like to keep at a birthday party? If not, can you think of something meaningful you might do or say next time to help make the occasion even more memorable?

2

The freedom party

To get into this next party, we will go back in time, and some distance in space. We are in the Jewish quarter of a small town in Turkey in about 200 BC. Like the Martian speaking English, you manage somehow to speak fluent Aramaic (the language most Jews spoke at the time). All day long you have been aware of a growing excitement. People shopping in a hurry. People busily going to and fro. It is springtime, and there is a sense of something about to happen. Then everything goes quiet in the street. You go over to one of the houses and knock on the door. A girl comes and lets you in, and brings you to the table, where the whole family is gathered.

‘What are you all doing?’

‘This is one of our special days. We call it Pesach.’

‘Pesach? What does that mean?’

‘Passing-over. It’s what happened when … well, you’ll see. Listen to the story.’

The older man at the head of the table is starting to speak. Actually, starting to read. He reads in a slightly sing-song voice. It’s an old story of the Jewish people, when they were slaves in Egypt. Everybody seems to know the story; they nod and smile as the tale unfolds.

‘We, the people of Abraham, the people called by God to be the light of the world … we went down into Egypt, and were slaves there. And our God brought us up from Egypt with a mighty hand and stretched-out arm. He condemned the Egyptians, but he passed over us, and brought us through the Red Sea and into the wilderness; and he gave us his law, and brought us into our promised land.’ The story goes on, and on, and on, through all the plagues in Egypt, all the dramatic details.

At one point a little boy, the younger brother of the girl who let you in, pipes up (he seems to be reading, or perhaps his mother is prompting him):

‘Why is this night different from all other nights?’

‘Because,’ says his father, reading still from his text, ‘this is the night when our God, the Holy One, blessed be he, came down to Egypt and rescued us from the Egyptians …’

‘But it isn’t,’ you whisper to your friend. ‘All that happened a long time ago.’

‘Yes it is,’ the girl whispers back. ‘This is the same night. It’s like a birthday party. And we are the same people. We are the people of Israel, the people God loved and chose and promised to rescue. We are the people who came out of Egypt.’

‘But … but … not you, surely?’ you ask. ‘It must have been your great-great-great-great-grandparents, with quite a few more “greats”.’

‘Yes, of course,’ she replies. ‘But that’s not the point. We are not just us, if you see what I mean. We are part of them, part of the whole of God’s people, God’s family. We are the same family that came out of Egypt. We are the same family that are having this meal in every Jewish home, everywhere in the world, tonight. This meal makes us all one.’

‘But why do you go on doing it? Surely it happened a very long time ago – how can it mean anything for you today?’

‘It tells us things about who we are. Things … oh, you know, things about God loving us, about God rescuing us. And after all, things are never easy for the Jews, you know. It wasn’t just the Egyptians. It was the Babylonians. And then the Persians and the Greeks. (It was after the Greeks ruled us that my family moved here, by the way.) And now we’re really worried, because there’s a new emperor in the next country, just over the border, where my uncle and aunt live, and he wants to conquer everywhere and make us all his slaves. We’re told he specially hates us Jews. So when we celebrate Pesach – ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Part One: How It All Began

- Part Two: The Thank-You Party