- 840 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The People's New Testament Commentary

About this book

M. Eugene Boring and Fred B. Craddock present this new one-volume commentary on the New Testament. Writing from the fundamental conviction that the New Testament is the people's book, Boring and Craddock examine the theological themes and messages of Scripture that speak to the life of discipleship. Their work clarifies matters of history, culture, geography, literature, and translation, enabling people to listen more carefully to the text. This unique commentary is the perfect resource for clergy and church school teachers who seek a reference tool midway between a study Bible and a multivolume commentary on the Bible.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

The Gospel according to Luke

INTRODUCTION

The Gospel of Luke, volume one of a two-volume narrative, tells the Christian story from the birth of John the Baptist through the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus. The story is continued in volume two, the Book of Acts, which tells the story from the beginning of the church in Jerusalem to the preaching of the gospel in Rome by Paul.

Luke not only wrote more of the New Testament than any other person (27.5 percent), he contributed the framework of understanding the Christian story that has dominated Christian understanding and the liturgical calendar throughout the centuries until the present: Old Testament promises/birth of Jesus/ministry/death/resurrection/ascension/descent of the Spirit/mission of the church/parousia.

Author

Like the other Gospels, the Gospel of Luke does not contain the author’s name but is anonymous. Like the other Gospels, the Gospel of Luke received a title in the second century, when the four canonical Gospels were selected from many others for inclusion in the canon, the normative collection of witnesses to the meaning of the Christian faith. From late in the second century, the author was understood to be Luke the companion of Paul mentioned in Phlm. 24 and 2 Tim. 4:11, called the “beloved Physician” in Col. 4:14, who speaks in the first person (“we”) in Acts 16:10–17; 20:5–21:18; 27:1–28:16. Some scholars regard this identification as accurate history; others, perhaps the majority, believe that the “we passages” of Acts reflect the author’s incorporation of the travel diary of one of Paul’s companions, or consider them a literary device to add vividness to the story. On the author’s medical language, see on Acts 3:7. In any case, the early church’s attribution of the Gospel to Luke was not primarily a matter of historical correctness but a means of affirming that the narrative is an authentic representative of the apostolic faith. We will refer to the author with the traditional designation Luke, while considering the author’s actual name to be unknown.

From the narrative itself we can learn that the author, though he may have been with Paul for a brief period, was not an eyewitness to the ministry of Jesus (see on 1:1–4). He was a sophisticated author who wrote excellent Greek, at a literary level superior to the other Gospels. If he was the Luke of Col. 4:14, he was certainly a Gentile (see Col. 4:11), and the narrative itself indicates the perspective of a Gentile Christian.

Genre and Readership

While Luke contains historical materials, it is clear that Luke is not concerned simply to write accurate biography or history but to bear witness to the truth of the Christian faith. “Theologically interpreted history” or “the story of God’s mighty acts in history” perhaps best captures Luke’s intent (see “Introduction to the Gospels”).

The dedication to Theophilus does not mean that the narrative was written to one individual. Luke’s readership is the wider public that has already been “informed” or “instructed” about the church and its message (1:4), but who need a deeper and more accurate understanding. This could be Christians who need a more informed faith, outsiders who are suspicious of Christianity, or both.

Sources

Luke refers to many prior authors who had compiled an account of Jesus’ life and teachings prior to his own writing (1:1). While “many” is part of the conventional style of such introductions, we know of at least two documents that Luke used as sources: The Gospel of Mark and a (now lost) collection of Jesus’ sayings called “Q.” In addition, Luke had various oral and perhaps written sources not documented elsewhere. This material peculiar to Luke, including his own editorial modifications and expansions, is designated “L,” so that all Luke’s composition may be identified as Mark (about 50 percent), Q (about 25 percent) and L (about 25 percent):

| 1:1–2:52 | L |

| 3:1–6:19 | Mark (+ Q for John the Baptist and Temptation sections) |

| 6:20–8:3 | Q + L |

| 8:4–9:50 | Mark |

| 9:51–18:14 | Q + L |

| 18:15–24:11 | Mark + L |

| 24:12–53 | L |

It is clear from this (somewhat rough) outline that Luke composes in blocks, alternating sections of Mark and Q, interspersed with his special materials and own editorializing.

Date and Place

Luke-Acts was certainly written after the latest event it narrates, Paul’s two-year imprisonment in Rome (Acts 28:30–31), i.e., after 63 CE. Since the Gospel of Mark is usually dated about 70 CE, Luke must have been written long enough after this to have considered Mark an authoritative source. Luke places himself in the second or third Christian generation (1:1–3) and seems to look back on the destruction of Jerusalem in 70 CE as having occurred sometime in the past (13:14; 19:43–44; 21:20). Thus most scholars place the composition ca. 80–90 CE, though there is no proof that the Gospel was written prior to the second century, when it first appears in quotations. There is no reliable evidence as to the place the document was composed, but this is not crucial for the Gospel’s interpretation.

Theological Themes

Luke writes as a theologian to help the church clarify its faith. He weaves together several theological themes, including the following:

1. Jesus as the “midst of time.” Jewish messianic hopes had looked forward to the coming of the Messiah and the establishment of God’s kingdom of justice and righteousness at the end of history. When the earliest followers of Jesus were convinced by the resurrection that Jesus was the Christ, they understood that the end of history had come and expected Christ to return in the near future. Luke reinterpreted the historical schema so that the Christ was seen as the defining center of history, followed by the extended period of the church’s mission before the coming of the end. He understood the “time of Jesus” to be a special one-year period in which the kingdom of God was realized on earth in the ministry of Jesus, preceded by the “time of Israel” and followed by the “time of the church.” The time of Jesus was the ministry of Jesus, baptism to crucifixion, which in Luke takes place within one year. During this unique one-year period, the kingdom of God was present and Satan was absent. Luke 3:1–2 identifies the year. At 4:13, after the temptation, Satan departs. In 4:19, Jesus announces the “year of the Lord’s favor,” with echoes of the Old Testament year of jubilee. In 9:22–23 Luke omits the reference to Satan at Caesarea Philippi (see Mark 8:33). In 11:20 Jesus’ victory over the demons means the kingdom of God is present. In 17:20, the kingdom is declared to be “in your midst.” At 22:3, on the last night of Jesus’ earthly life, Satan returns. At the Last Supper Jesus explains to his disciples that the special time of the kingdom is over, that they will carry out the church’s mission under the ordinary conditions of this world’s continuing history (22:35–38). The church looks backward to the time when the kingdom was manifest in the life of Jesus and forward to the end of history, when it will be manifest to all.

2. God as the champion of the poor and oppressed. See 1:46–55; 2:8–14, 24; 3:10–14; 4:16–21; 6:20–23; 14:21–23; 16:19–31; Acts 2:44–47; 3:6; 4:32–35; 11:27–30.

3. Repentance and forgiveness of sins as the content of thegospel. See 3:3; 17:3; 24:47; Acts 2:38; 5:31; 8:22, and numerous other Lukan references to “repentance,” which Luke uses twenty-five times, more than any other New Testament writer.

4. The Holy Spirit. As the power of God at work in Israel, Jesus, and the church, the Spirit binds their history together into the story of God’s mighty acts in history (there are seventy-four references to the Spirit in Luke-Acts, e.g., 1:15, 35, 41,67; 2:25–27; 3:16; 4:1, 14, 18; 10:21; 11:13; 12:10, 12; Acts 1:2, 5, 8, 16; 2:4, 17, 38; 4:31; 5:32; 6:3; 8:17; 9:31; 10:44–45; 11:28; 13:2; 15:28; 19:2–6; 28:25).

5. The church as good citizens. Neither Jesus nor his followers represent a political threat to the world order; though Christians are suspected of being politically subversive and the enemy of Rome, in Luke-Acts the church takes its place in history as good citizens alongside other institutions (1:1–4; 2:1ff.; 7:1ff.; 13:31ff.; 20:20–26; 23:13–16, 47; Acts 16:35–39; 18:12–17, and the other trial scenes in Acts when Paul appears before Roman governors).

6. God as the Lord of the whole world and history. God is not just the one who acts in the biblical and Christian history (Luke 2:1; 3:1; 24:47; Acts 14:17; 17:24–28; 26:26). The Christian story is set by God the Creator in the context of the whole world and its history, since the church has a mission to the whole world.

Outline

| 1:1–4 | Prologue |

| 1:5–2:52 | The Birth and Childhood of John and Jesus |

| 3:1–4:13 | Preparation for Jesus’ Ministry |

| 4:14–9:50 | Jesus’ Ministry in Galilee |

| 9:51–19:27 | The Journey to Jerusalem |

| 19:28–21:38 | Jesus’ Ministry in Jerusalem |

| 22:1–24:53 | Jesus’ Passion and Resurrection |

For Further Reading

Craddock, Fred B. Luke. Interpretation: A Bible Commentary for Teaching and Preaching. Louisville, KY: Westminster/John Knox Press, 1990. Some of the material on Luke in the pages that follow has been drawn from this more expansive treatment.

Culpepper, R. Alan. “The Gospel of Luke.” In The New Interpreter’s Bible, vol. 9. Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1995.

COMMENTARY

1:1–4

PROLOGUE

Among New Testament authors, only Luke prefaces his Gospel with a statement of his intention and method. In the Gospel, only here does the reader hear the narrator’s voice in the first person, which reemerges briefly in the “we passages” of Acts (see on Acts 16:10–17). The preface functions as the vestibule that leads readers into the narrative world of the Gospel, where they can see and hear the story for themselves.

Luke 1:1–4 is one elegantly constructed sentence, at the literary level of historical works written for sophisticated readers of the first century. In Luke-Acts, Christian literature begins to address people of culture and education both within and outside the church, for one dimension of the author’s purpose is to show that the Christian faith is not about something “done in a corner” (Acts 26:26) but belongs to the mainstream of world history. Theophilus is representative of such anticipated readers. Except for the fact that the author’s name is not mentioned, the style and format are conventional, as in the prefaces to other historical works of the Hellenistic world (see, e.g., Josephus, Against Apion 1.1).

1:1 An orderly account: This does not mean that he is attempting to restore the correct chronological order of the life of Jesus, for we know from the way he handles his sources that this kind of historical accuracy was not his concern (see on 4:14–30). His purpose seems rather to present an account that shows how the events fit into God’s plan for the history of salvation, a theological order, rather than historical precision. The same word is translated “step by step” in Acts 11:4. So also, Luke’s purpose that Theophilus may know the truth deals more with theological truth than with historical fact—though Luke is not unconcerned with the latter. We get Luke’s understanding of truth by studying his narrative, not by importing our own ideas of accuracy and truth.

1:3 Most excellent Theophilus: The reference to Theophilus is not a direct address as in a personal letter—Luke addresses a much wider readership—but is more like a dedication. The Greek name Theophilus was also used by Jews and means literally “friend of God.” Thus some interpreters have thought Luke was using the word symbolically to indicate his narrative is addressed to all friends of God whoever they were. More likely, Theophilus is an individual member of the Greco-Roman nobility, either actual or ideal. Since “most excellent” is found elsewhere in the New Testament only as a title for Roman governors (Acts 23:26; 24:3; 26:25), it may be that Luke has in mind Roman officials who must make decisions about Christianity. The word translated instructed (1:4) can also mean “informed, told” (as in Acts 21:21, 24), so Luke could have in mind Jewish Christians or Roman officials who had heard certain things about the Christian faith as represented by the Gentile Pauline churches, and writes his two volumes to give such people a more accurate understanding of what the church is about. Then Luke-Acts would have an apologetic purpose, i.e., it intends to defend the truth of the faith against misunderstandings and attacks. On the other hand, if Luke uses the word in the sense of “instructed” (as in 18:25), Theophilus represents Christian believers seeking a deeper understanding of their own faith. Thus whether or not Luke intended the “us” of 1:1 to include the original Theophilus, it includes all present readers of the Bible and invites us into the narrative that follows, to hear it as our own story.

1:5–2:52

THE BIRTH AND CHILDHOOD OF JOHN AND JESUS

This division is a narrative unit; 3:1 begins afresh. Infancy Narrative and Birth Story are traditional titles; the unit actually stretches from the annunciation of the birth of John the Baptist through

the story of the boy Jesus in the temple at age twelve. Four features of the story as a whole require attention before study of its details.

1. Length. The story is a substantial narrative in itself, more than 10 percent of Luke’s total narrative, more than three times the length of the only other New Testament narrative of Jesus’ birth (Matt. 1:18–2:23), and longer than several of the books of the New Testament. Luke does not rush his readers into the heart of the story but prepares the way, just as John prepares the way for Jesus.

2. Style. Even the casual reader perceives the shift in style between verses 4 and 5. Those who are steeped in the Old Testament now find themselves at home, after the sophisticated introduction in the Greek style. The stories of Zechariah and Elizabeth, Mary (“Miriam” in Greek) and Joseph, Simeon, and Anna bring to mind the stories of Abraham, Sarah, and the birth of Isaac (Gen. 18–21); Elkanah, Hannah, and the birth of Samuel (1 Sam. 1–3); and Manoah, his wife, and the birth of Samson (Judg. 13). The story reads like the rest of the Old Testament and illustrates Luke’s intention to join the story of John and Jesus to the story of the mighty acts of God in the Jewish Scriptures as their climax and fulfillment.

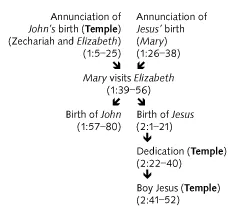

3. Form. It is artfully constructed of seven sections, the first five of which are arranged in the rhetorical pattern of a chiasm (shaped like the Greek letter Chi, which looks like an English X). The separate stories of John and Jesus are brought together at the visitation, then separated again for the birth of John and Jesus. To this chiastic arrangement two scenes in the temple are appended, giving the structure shown in Figure 10.

The diagram suggests that Luke disrupted his own neat scheme in order to add two scenes in the temple, thus beginning and ending the section in the temple. The structure itself is the first indication that the Birth Story is not a prelude but an overture, not dispensable preliminaries but a Gospel in miniature that signals in advance major themes of the Gospel. One scholar has found twenty Lukan themes that are anticipated in chaps. 1–2: banquet, conversion, faith, fatherhood, grace, Jerusalem, joy, kingship, mercy, “must” (the divine necessity), poverty, prayer, prophet, salvation, Spirit, temptation, today, universalism, way, witness.

Figure 10. Chiastic Structure of Luke 1:5–2:52

4. Distinctiveness. Luke tells the story in his own way, to bring out the theological meaning of the birth of Jesus. The genre is akin to Hebrew midrash, in which biblical stories were imaginatively amplified and interpreted to bring out their present meaning. It is a misdirected effort, then, to attempt to harmonize Luke’s story with that of Matthew 1:18–2:23 (which is likewise midrashic storytelling, not factually accurate history). For instance, Luke’s story of Jesus’ birth begins in Nazareth and proceeds to Bethlehem, while Matthew’s story begins in Bethlehem and moves to Nazareth. Each author has good theological reasons for telling the story this way, but their intended message is appropriated when the distinctive meaning of each is perceived, not from attempting to combine them. Not only are there no magi in Luke, and there is no room for them; there are no shepherds in Matthew, and to insert them is to disrupt Matthew’s story. Where can the flight to Egypt (Matt. 2:13–21) be fitted into Luke’s story? Where can the dedication in the temple (Luke 2:21–40) be inserted into Matt...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Introduction

- Introduction to the Gospels

- The Gospel according to Matthew

- The Gospel according to Mark

- The Gospel according to Luke

- The Gospel according to John

- The Acts of the Apostles

- Introduction to the Pauline Letters

- The Letter of Paul to the Romans

- The First Letter of Paul to the Corinthians

- The Second Letter of Paul to the Corinthians

- The Letter of Paul to the Galatians

- The Letter of Paul to the Ephesians

- The Letter of Paul to the Philippians

- The Letter of Paul to the Colossians

- The First Letter of Paul to the Thessalonians

- The Second Letter of Paul to the Thessalonians

- The First Letter of Paul to Timothy

- The Second Letter of Paul to Timothy

- The Letter of Paul to Titus

- The Letter of Paul to Philemon

- The Letter to the Hebrews

- The Letter of James

- The First Letter of Peter

- The Second Letter of Peter

- The First Letter of John

- The Second Letter of John

- The Third Letter of John

- The Letter of Jude

- The Revelation to John

- For Further Reading

- Index of Excursuses

- List of Figures

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The People's New Testament Commentary by M. Eugene Boring,Fred B. Craddock in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Biblical Commentary. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.