![]()

Chapter One

What Is Q?

By the fourth century of the Common Era, Christians had to decide which of their writings should be regarded as authoritative, which were useful but not normative, and which should be rejected as deviant or heretical. This process was necessary, for by that time many Gospels, letters, apocalypses, and sundry treatises existed, each vying for authority within local Christian communities.

For many of these documents, we have only names. But what an assortment of names there are! There were Gospels written under the names of virtually all of the men and women associated with Jesus; apocalypses ascribed to Peter, Paul, and James; acts of Andrew, Peter, Paul, Thomas, John, and Pilate; and letters purporting to come from a host of personages mentioned in the New Testament. Most of these have perished, but a handful survives, mostly in tiny fragments or in brief excerpts quoted by other writers.

Occasionally the sands of Egypt give up one of these lost documents as they did in the 1890s when fragments of the Gospel of Thomas were discovered in Upper Egypt and later, in 1945, when Coptic versions of the Gospel of Thomas, Gospel of Philip, the First and Second Apocalypses of James and many other extracanonical documents were found. More often, we must reconstruct the contents of these lost documents through a careful analysis of the later documents which quoted or referred to them, as we must do in the case of Paul’s original letter to the Corinthians. This is what must be done in the case of the Sayings Gospel Q.

Q is neither a mysterious papyrus nor a parchment from stacks of uncataloged manuscripts in an old European library. It is a document whose existence we must assume in order to make sense of other features of the Gospels. Although the siglum Q seems rather mysterious and the idea of a lost Gospel sounds like it comes from the plot of a modern thriller, the truth is a little more banal. “Q” is a shorthand for the German word Quelle, meaning “source.” Scholars did not invent Q out of a fascination for mysterious or lost documents. Q is posited from logical necessity.

Put simply, the most efficient and compelling way to explain the relationship among the Synoptic Gospels—Matthew, Mark, and Luke—is to assume that Mark was used independently as a source for Matthew and Luke. Matthew and Luke, however, share some material that they did not get from Mark, about 4,500 words. It is this material that makes up the bulk of Q. It may be that some day we will have more tangible evidence of Q—perhaps a papyrus fragment of this document or other early documents that quoted Q. For now, however, we must rely on what can be deduced about this document from the two Gospels which used it, Matthew and Luke. This chapter will explain the reasons for positing Q. It begins with some observations about the Synoptic Gospels.

A Literary Relationship among the Gospels

Comparison of the Synoptic Gospels indicates that some sort of literary relationship exists among them. Put simply, two have copied from the other, or one has copied from the other two.

There are several reasons for this conclusion. First, the first three Gospels often display a high degree of verbatim agreement. Compare, for example, the stories of Jesus calling the four fishermen (Matt. 4:18–22 | | Mark 1:16–20). The strong verbal agreement is obvious. In Greek, Matthew’s pericope contains eighty-nine words; Mark has eighty-two. They agree on fifty-seven or 64 percent of Matthew’s words and 69.5 percent of Mark’s (the word count in English will differ a bit). This degree of verbal agreement is at least as high as in other instances where we know one author to be copying another.

The agreements are significant, since they include not only the memorable saying, “Follow me and I will make you fishers of men,” which might be memorized, but also the rather unnecessary explanation, “for they were fishermen.” Moreover, Matthew and Mark agree even on very small details, for example, the type of net that was used. Matthew calls it an amphibalestron, a circular casting net and only one of the several types of nets in use in the first century CE. Mark uses the cognate verb, amphiballein. Both agree in mentioning the father of James and John even though he, like Mark’s hired help, plays no special role in the story.

The agreements between Matthew and Mark do not extend simply to choice of words, but include the order of episodes. Both accounts name Simon first, then Andrew, then James, then John, even though other lists of these disciples—Mark 3:16–18; 13:3 and the Gospel of the Ebionites, for example—name these disciples in a different order. There is no special reason for narrating the call of Peter and Andrew first, and only then James and John; yet Matthew and Mark agree on this sequence. In the Gospel of John, by contrast, Andrew comes first, then Peter, and James and John are not mentioned at all (John 1:35–42). Hence, the agreement of Matthew with Mark to narrate the call of the four disciples in the same order, and in the same way, agreeing on various minor details, points to literary dependence: one has copied the other, or both have copied a common source.

Similar observations could be made of pericopae that Luke has in common with Mark. Take, for example, the call of Levi, Mark 2:13–14 and Luke 5:27–28. Mark has thirty-six words in Greek, Luke has twenty-four, but they agree on sixteen of those words or two-thirds of Luke’s words. What is perhaps most remarkable is that the call of Levi is narrated at all. Levi appears only here in known Gospel tradition; he is never mentioned again by any other source. (Matthew changed the name to “Matthew,” probably to connect this disciple with the one named in Matt. 10:3 | | Mark 3:18). That Mark and Luke would choose to relate the call of so obscure a disciple, both putting this call immediately after the story of the cure of the paralytic (Mark 2:1–12 | | Luke 5:17–26) suggests that one account has borrowed from the other, or that both are using a common source.

Finally, we can compare Matthew and Luke and again find instances of very strong verbal agreement. Take, for example, John the Baptist’s address to the crowds (Matt. 3:7–10 | | Luke 3:7–9). The agreement between Matthew and Luke is remarkable: Matthew has seventy-six words in Greek, sixty-one or 80 percent in agreement with Luke. Luke has seventy-two words, sixty-one or 85 percent agreeing exactly with Matthew. Although there are slightly differing introductions, the words of John are virtually identical, apart from Matthew’s singular noun “fruit” and its dependent adjective “worthy” in place of Luke’s plural noun and adjective. Matthew has “do not presume” in contrast to Luke’s “do not begin.” Luke also has an extra kai in verse 9 which is not easily translatable in English but is used for emphasis.

This type of agreement includes not only the choice of vocabulary, but extends to the inflection of words, word order, and the use of particles—the most variable aspects of Greek syntax. If Matthew and Luke were reproducing this oracle freely from memory, it is most unlikely that they would agree so closely on such highly variable elements of Greek. This type of agreement can be explained only on the supposition that Matthew copied Luke or vice versa, or both used a common written source.

There is yet another reason to think that the Synoptics are related through literary copying. If we align the three Gospels in parallel columns, as is done in modern synopses such as Kurt Aland’s Synopsis of the Four Gospels or Burton Throckmorton’s Gospel Parallels,1 we see that the three often agree in relating the same incidents in the same relative order.

Although in the early part of Matthew (3–13), Matthew and Mark have a rather different order of events, from Matthew 14:1 and Mark 6:16 onward the two Gospels agree almost completely in sequence. The significance of this strong agreement cannot be missed. If Matthew and Mark were completely independent tellings of the story of Jesus, it is unlikely that the writers would choose to relate all stories and sayings in the same order, especially when there was no thematic or narrative reason to do so. For example, there is no special reason why the story of Jesus’ argument with the Pharisees about washing hands (Matt. 15:1–20 | | Mark 7:1–23) should appear just before the story of the Syro-Phoenician woman’s daughter (Matt. 15:21–28 | | Mark 7:24–30), or why the controversies about payment of taxes (Matt. 22:15–22 | | Mark 12:13–17) comes just before the controversy about the resurrection (Matt. 22:23–33 | | Mark 12:18–27). Yet Matthew and Mark agree in these sequences and in many more pericopae. Luke and Mark agree in sequence even more strongly than do Matthew and Mark, and this indicates that copying has occurred.

Thus, we can conclude that some kind of literary relationship exists among the first three Gospels. At this point we cannot decide who is copying whom, but it is clear that both the wording and the sequence of the three Gospels is the result of literary interaction.

Mark as the Earliest Gospel

Mark is usually treated as the earliest of the three Gospels and thought to have served as a literary source for Matthew and Luke. There are two steps in arriving at this conclusion.

Mark as Medial

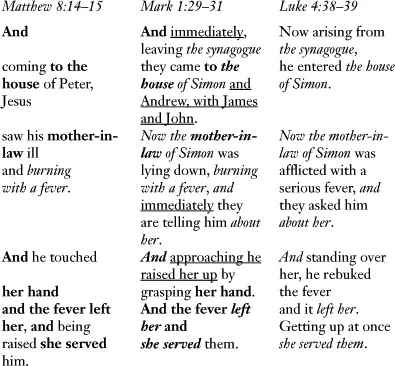

Let us begin with the materials in the Synoptics where Matthew, Mark, and Luke have parallel stories. While Matthew often agrees with Mark’s wording of a story or saying, and while Luke often agrees with Mark’s wording, it is relatively rare to find Matthew and Luke agreeing when Mark has a different wording. Take, for example, the story of the healing of Simon’s mother-in-law in Matthew 8:14–15 | | Mark 1:29–31 | | Luke 4:38–39:

Matthew and Mark agree in much of their wording (in bold), and Mark and Luke agree in many details (in italic). Matthew and Mark both use a participial construction of a verb, pyressein, “to burn with a fever,” while Luke uses the related noun pyretos, “fever,” which Matthew and Luke use later. Matthew and Mark have Jesus heal by touching or grasping the woman’s hand and both have the phrase “and the fever left her.” Luke mentions “fever” here, but it is the object of the verb “rebuke” rather than the subject of the verb “left.”

Mark and Luke also agree, referring to Simon’s house and Simon’s mother-in-law, and both relate an exchange between Jesus and the disciples “about her.” Note by contrast that in Matthew Jesus sees the woman and takes the initiative to heal her without any prompting from the disciples. And while Matthew says that she arose and served him (Jesus), Mark and Luke have the women serve all the disciples (“them”).

What is important to note here is that Matthew and Luke do not agree with each other against Mark in any detail. It is true that Matthew and Luke fail to repeat some of the details in Mark: “immediately” (twice); “and Andrew, with James and John”; and “approaching he raised her up” (underscored). But they do not agree positively against Mark.

This pattern, which could be illustrated by reference to other pericopae as well, suggests that the relationship between Matthew and Luke is indirect rather than direct. If there had been a direct connection between Matthew and Luke, we should expect Matthew sometimes to agree with Luke against Mark. But agreements of this sort are in fact quite uncommon (although there are some that we shall have to discuss later). The fact that Matthew and Luke tend to agree with Mark, but not against Mark, means that Mark is medial. This does not in itself imply that Mark is the earliest of the three, although that is one possibility. In fact several arrangements of the Gospels are possible with Mark as the middle term (see fig. 1).

In each of these arrangements, there is no direct connection between Matthew and Luke, and, hence, no possibility of them agreeing with each other apart from Mark, except by coincidence. In the first straight-line arrangement (a), if Mark changed Matthew’s wording, Luke would not agree with Matthew (except by coincidence), since he has no direct access to Matthew. The same is true in the second straight-line arrangement (b): if Mark changed Luke’s wording, Matthew could not agree with Luke except coincidentally. Or in the simple branch solution (c), in cases where Matthew changes Mark, it would be unexpected to see Luke always changing Mark in the same way. If we understand the pericope mentioned above on a simple branch solution, Matthew changed Mark’s “Simon” to the more common “Peter.” He has Jesus take the initiative in the healing and he adds that Jesus heals by mere touch. Note that Luke lacks all of these Matthean changes. On the other hand, Matthew lacks Luke’s additions to Mark, the qualification of the fever as “serious” and Jesus rebuking the fever. According to this model, Matthew and Luke independently edited Mark, but cannot agree against Mark, since neither has direct access to the other’s work.

The fourth model, conflation (d), also accounts for nonagreement against Mark but in a different way. On the first three models, there are no Matthew-Luke agreements against Mark because Matthew and Luke are not in direct contact. In the conflation model, Mark chooses not to disagree with Matthew and Luke when he sees them in agreement. In the pericope above, Mark saw that both Matthew and Luke had “to the house,” “mother-in-law,” and “she served” and so reproduced this agreement. But where Matthew and Luke had different wording, Mark sometimes sided with Matthew, taking over the entire phrase “and the fever left her,” but also took over from Luke the mention of a synagogue and the concluding phrase, “she served them.” On this model, Mark also added a few details of his own (underscored).

This model is more complicated than the others, since it presupposes that Mark had before him both accounts and moved back and forth between the two, picking elements from one, then the other. Such a model is not logically impossible, but examination of how other authors worked who combined two sources reveals that no known ancient author would have taken the trouble to compare sources so closely and to zigzag between them. An ancient conflator would more likely have taken over Matthew’s account or Luke’s but not bothered to micro-conflate them.2

A second set of data also points to the conclusion that Mark is medial. If we compare the sequence of episodes in each of the Gospels, an important pattern emerges. While Matthew sometimes relates an episode in a different sequence than Mark and Luke, and while Luke sometimes relates an episode in a different sequence than Mark and Matthew, Matthew and Luke never agree in locating an episode differently from Mark’s sequence.

When, for example, Matthew relocates a Markan episode such as Mark 5:1–20, the exorcism of a demoniac, to an entirely new location (Matt. 8:28–34), Luke agrees with Mark, not Matthew. There is only one episode in the Synoptics where both relocate a text of Mark (3:13–19), but they do so to different locations, Matthew moving it to a point before Mark 2:23–3:12 (| | Matt. 12:1–16), a series of controversy stories, while Luke simply inverts the order of Mark 3:7–12 and 3:13–19 so that the naming of the Twelve comes before a list of the various peoples that came to see Jesus. That is, even where both Matthew and Luke disagree with Mark’s sequence, they also disagree with each other.

These data reinforce the earlier conclusion: Mark is medial. In matters of sequence, we find Matthew agreeing with Mark’s order, and Luke agreeing with Mark’s order, but we never find Matthew and Luke agreeing to place a story where Mark has an entirely different placement. This datum suggests that there is no direct relationship between Matthew and Luke. Any of the possible arrangements of three Gospels indicated in figure 1 might account for these data.

How, then, d...