eBook - ePub

Motivation and the Primacy of Perception

Merleau-Ponty's Phenomenology of Knowledge

This is a test

- 264 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Merleau-Ponty's phenomenological notion of motivation advances a compelling alternative to the empiricist and rationalist assumptions that underpin modern epistemology.

Arguing that knowledge is ultimately founded in perceptual experience, Peter Antich interprets and defends Merleau-Ponty's thinking on motivation as the key to establishing a new form of epistemic grounding. Upending the classical dichotomy between reason and natural causality, justification and explanation, Antich shows how this epistemic ground enables Merleau-Ponty to offer a radically new account of knowledge and its relation to perception. In so doing, Antich demonstrates how and why Merleau-Ponty remains a vital resource for today's epistemologists.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Motivation and the Primacy of Perception by Peter Antich in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Philosophy & Phenomenology in Philosophy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

PhilosophySubtopic

Phenomenology in PhilosophyPART I

Defining the Account

CHAPTER 1

MERLEAU-PONTY’S PHENOMENOLOGY OF MOTIVATION

Though, as we will see, motivation plays a significant role throughout Merleau-Ponty’s corpus, the principal texts in which he articulates this concept occupy only a few pages (PhP, 47–51).1 To draw out this phenomenon, then, we will have to do considerable interpretative work, and this is the task of the present chapter.

In brief, the point of Merleau-Ponty’s discussion of motivation in the Phenomenology of Perception is that it allows us to understand an essential fact about perception, namely, that the world comes to us as already bearing a sense. As Merleau-Ponty puts it, perception presents us with a “spontaneous valuation [valorisation spontanée]” (PhP, 465), or we might also say a “spontaneous sense.” For example, consider the Gestalt theory result that the following series

* * *

is always perceived as “six groups of dots, two millimeters apart.” I do not see the dots, and then see them grouped thus. Indeed, there is no need for me to arrange them. I just find them that way. In Merleau-Ponty’s words, “Everything happens as if, prior to our judgment and our freedom, someone were allocating such and such a sense to such and such a given constellation” (PhP, 465). What examples like this show, according to Merleau-Ponty, is that perception reveals the world as meaningful, as laden with a sense that we do not actively attribute to the world. At the same time, neither can we say that this meaning is simply in the objects, considered apart from us, since, for example, there is nothing about the physical properties of the dots that requires one grouping rather than another. Instead, the grouping must arise spontaneously, through the contact between myself and the world, or, rather, through perception itself. “Motivation” describes the process through which these spontaneous meanings arise, that is, the way in which they are grounded.

First, let me try to get a basic ontology of motivation into view. I understand motivation as a type of grounding. In thinking of motivation as a ground, I understand grounding in a broad sense, largely abstracted from many of the concerns raised in the contemporary literature on grounding. I’ll simply say that if X grounds Y, then X answers “why?” questions about Y. As such, grounds are relations: grounding is a relation that grounding and grounded bear toward each other.

Now, there is more than one way to answer “why?” questions. I briefly touched on two kinds of answers in the introduction: explanation (causality) and justification (reason). My general contention is that motivation offers a third kind of answer, one not reducible to justification or explanation. Motivation, as we will see, is the form of grounding characteristic of our bodily spontaneity. As such, it can be found throughout human experience: there are motives for action, motives for perception, motives for beliefs, et cetera.2 Since Merleau-Ponty treats motivation primarily in the context of perception, I will, in this chapter, focus on motivation as a perceptual ground. In later chapters, I will consider how motivation works as a ground of beliefs (i.e., as an epistemic ground).

So, in brief, motivation, like reasons or natural causes, is a type of grounding relation. Naturally, different kinds of things can serve as grounds and different kinds of things can be grounded. Substances, events, actions, properties, and so on all can answer or be the object of “Why?” questions. But we can be more specific about the kinds of things that can stand in motivational relations. In speaking of motivation, we are, according to Merleau-Ponty, speaking about a relation between phenomena or meanings. As he puts it, motivation allows us to describe how “one phenomenon triggers another, not through some objective causality [efficacité objective], such as one linking together the events of nature, but rather through the sense [sens] it offers” (PhP, 51). So, Merleau-Ponty conceives motivation as a grounding relation not between events in the natural world, but between phenomena or meanings.

At the same time, neither does Merleau-Ponty think of motivation as the product of purely active, mental control, the way our judgments or decisions are supposed to be the product of mental activity. Instead, in a manner we will have to spell out in the following, Merleau-Ponty thinks of motivation as the form of grounding characteristic of our bodily spontaneity. To be clear, in speaking of the body in this way, I am not thinking of the body as simply another natural object, but as what we might call the “lived body” (i.e., the body my experience inhabits and that bears my experience into the world). So when I speak of our bodily spontaneity, I have in mind, for example, the way our perceptual capacities are spontaneously attuned to the perceptual field so as to make sense of it, prior to my active, mental deliberation and judgment. Provisionally, then, we can provide the following description of motivation: motivation is a grounding relation that phenomena or meanings (sens) can bear toward each other in virtue of our bodily spontaneity.

But, in order to understand what distinguishes motivation from reason or causality, I need to be more precise about the kind of grounding relation we are dealing with. This is the purpose of the present chapter. Specifically, I will forward nine claims about motivation. These claims are not meant to compose an exhaustive list of the distinctive features of motivation, but simply to capture Merleau-Ponty’s main claims about this form of grounding and to identify those features that will be indispensable in the coming chapters. These claims are the following:

1. Motivation is spontaneous (i.e., embodied).

2. Motives don’t require explicit awareness to operate.

3. Motives operate through their meaning.

4. Motivation is an internal relation.

5. Motivation is a reciprocal relation.

6. Motivation tends to equilibrium and determinacy.

7. Motivation can be normative.

8. The output of motivation transcends its input.

9. Motives are neither reasons nor causes.

Before I defend these claims, however, let me provide a few examples of perceptual motivation, which will help anchor my discussion.

THE SHIPWRECK

Merleau-Ponty writes, “If I am walking on a beach toward a boat that has run aground, and if the funnel or the mast merges with the forest that borders the dune, then there will be a moment in which these details suddenly reunite with the boat and become welded to it” (PhP, 17). What he describes here is a perceptual gestalt shift: a scene that had appeared as a bank of trees is reinterpreted as a shipwreck. Ordinarily in such cases, one does not begin by noting various incongruities, for example, in the interpretation of the vertical poles as tree trunks—perhaps that they are too long or too short, not quite the right color, or that they lack branches—and then deliberately suggesting a new interpretation. While it is certainly possible to proceed in this manner, one need not, and more likely, something like the following occurs. As one approaches the ship a vague sense of tension within one’s perception will grow; one senses a problem in the interpretation, without being able to adduce evidence for the problem (just as, for example, one can sense that something has changed in a room without being able to identify the difference), perhaps without ever yet paying attention to the building awareness of a problem. And then, suddenly, and without one’s express decision, a resolution announces itself in the form of a new grouping of the perceptual field: one sees the scene anew, now in a more stable, more complete perception.

THE BELL TOWER

Objects interposed between me and the one I am focusing upon are not perceived for themselves. But they are, nevertheless, perceived, and we have no reason to deny this marginal perception a role in the vision of distance since the apparent distance shrinks the moment a screen hides the interposed objects. The objects that fill the field do not act on the apparent distance like a cause on its effect. When the screen is moved aside, we see the distance being born from the interposed objects. This is the silent language perception speaks to us: the interposed objects, in this natural text, “mean” a larger distance. It is, nevertheless, not a question of the logic of constituted truth (one of the connections that objective logic knows), for there is no reason for the bell tower to appear to me as smaller and farther away the moment that I can see more clearly the details of the hills and the fields that separate me from it. There is no reason, but there is a motive. (PhP, 49–50)

The presence of objects interposed between myself and an object to which I am attending motivates a sense of the size and distance of the object. I needn’t attend to the hill for it to make the bell tower appear farther away, and yet the moment the hill is blocked from view, the perceived distance shrinks.

THE MOON

The same is true of the perceived size of the moon. I see the full moon on the horizon as large, and as smaller the farther it travels into the night sky (cf. PhP, 270–71). But if, as the moon sits large just above the horizon, I screen the horizon from my vision, the moon will suddenly shrink. Unknown to me, the proximity of the moon to the horizon motivates my perception of the moon’s size. Thus, in proximity to the terrestrial world, the moon appears large; adrift in the sky, it appears modest. Of course, I do not think (i.e., judge) that the moon actually shrinks as it rises or as I screen the horizon from view—but I do see it as smaller. Merleau-Ponty writes, “The parts of the [perceptual] field act upon each other and motivate this enormous moon on the horizon, this measureless size that is nevertheless a size” (PhP, 34).

THE PORTRAIT

It took centuries of painting before the reflections upon the eye were seen, without which the painting remains lifeless and blind. . . . The reflection is not seen for itself, since it was able to go unnoticed for so long, and yet it has a function in perception, since its mere absence is enough to remove the life and the expression from objects and from faces. The reflection is only seen out of the corner of the eye. It is not presented as the aim of our perception, it is the auxiliary or the mediator of our perception. It is not itself seen, but makes the rest be seen. (PhP, 322–23)

The presence of a reflection in a portrait subject’s eye transforms our perception of the subject, imbuing it with the quality of liveliness.3 Supposing it took centuries for the reflection to be noticed for itself, it must have this effect without being explicitly recognized by the viewer. There are thus grounds at work in perception to the function of which explicit attention is accidental, attendant at most.

I take it that each of these perceptions is grounded in a common manner: they arise spontaneously, without the intervention of active thinking. Let us say, then, provisionally, that these perceptions are motivated. Assuming there is a phenomenon common to these cases, let us now attempt to define its essential features.

1. MOTIVATION IS SPONTANEOUS (I.E., EMBODIED)

I started by noting that motivation is responsible for the spontaneous sense we find in experience. More fundamentally, this means that motivation, as a process of grounding, occurs spontaneously. In Merleau-Ponty’s usage, a process is “spontaneous” if it is not the product of active decision. I do not decide upon a course of motivation, nor do I actively forge the relation between a motive and its motivatum. Instead, a motive spontaneously grounds its motivatum, presenting me with a sense about which I can only subsequently make decisions. As we just saw, the moon appears larger the closer it is to the horizon, but not because I have decided to see the moon as larger. Indeed, I may well decide that this change in appearance is irrational, since I know that the moon itself has neither shrunk nor retreated into the distance. Motivation is, then, not entirely within the realm of responsibility. But neither is it simply passive, something we receive from the world. What is simply passive, namely, the optical image of the moon, is largely unchanged by the moon’s course in the night sky. And if the transformation in appearance cannot be grounded in the efficacy of the world alone, then it must be partially grounded in me, or, rather, in my perceptual capacities. In this sense, the transformation is neither active nor passive, but spontaneous.

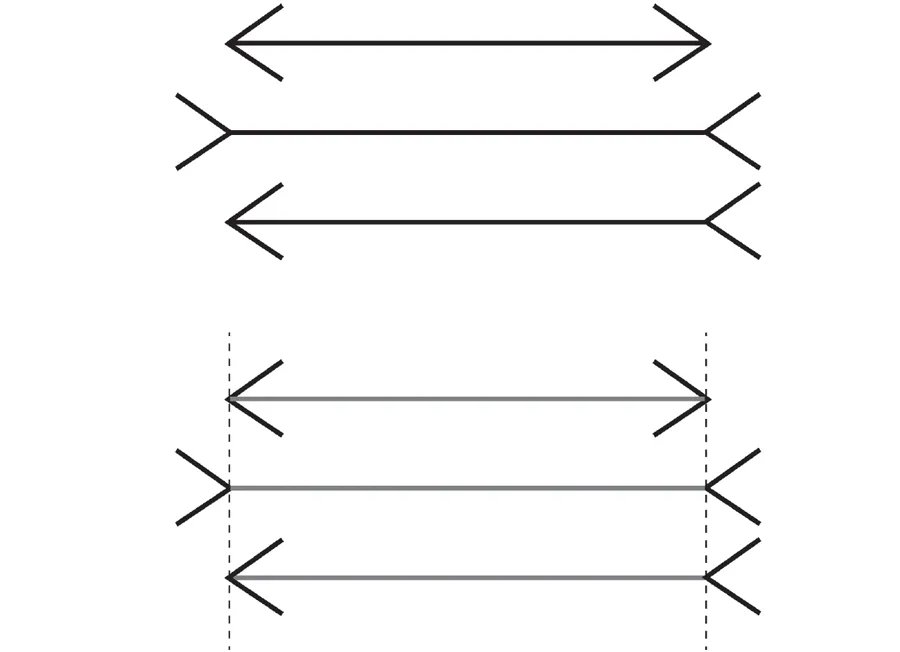

To be clear, then, I understand spontaneity in distinction from both activity (the sort of direct control we exercise, for example, in making decisions) and passivity (the mere receptivity we have with respect, for example, to the light entering the cornea and having certain causal effects on the brain). In my opening example, the gestalt “six groups of dots two millimeters apart” is spontaneously attributed to the series; it is not the product of decision or deliberation, and if asked I can give no reason as to why they should be grouped this way rather than another. Perhaps I can attempt to rationalize the grouping (e.g., “It makes sense to group dots that are closer together”). But these rationalizations are purely speculative, since I have no access to having been guided by such reasons. More importantly, if I happened to have reasons favoring an alternate grouping, I would not be able simply to revise my perception. For example, in the case of the Müller-Lyer illusion (see fig. 1.1), my “spontaneous valuation” of the lines as of different lengths or as ambiguously long conflicts with the reasons I have for thinking they are exactly the same length (e.g., that I have measured the lines). So, while I am free actively to affirm or deny the spontaneous sense that I perceive, I am not free to alter this sense itself: despite my knowledge to the contrary, the lines still appear unequal.

FIGURE 1.1. Müller-Lyer illusion. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Of course, it’s entirely plausible that perception is sometimes influenced by our active capacities. If a friend sees a different gestalt before us than I see, I will ask myself, “Could it be like she says?” Then it can happen that as I search the image, somehow the perceptual field changes, and my friend’s interpretation comes into view. It is true, at times, of perception that if I seek, I shall find. I have some leeway with respect to my perception of ambiguous figures, for example. But it does not always happen this way. I cannot always make myself see even what I know to be true: for example, I can know that the Müller-Lyer lines are equal, and yet see them only as ambiguously long or ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Epigraph

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Abbreviations

- Introduction

- Part I. Defining the Account

- Part II. Defending the Account

- Part III. Motivation and Pure Reason

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index