This is a test

- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

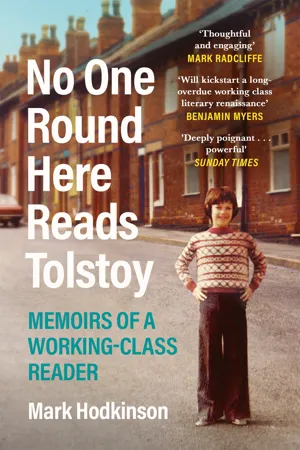

No One Round Here Reads Tolstoy

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Mark Hodkinson grew up among the terrace houses of Rochdale in a house with just one book. Today, Mark is an author, journalist and publisher. He still lives in Rochdale but is now surrounded by 3, 500 titles, at the last count.No One Round Here Reads Tolstoy is his story of growing up a working-class lad during the 1970s and 1980s. It's about the schools, the music, the people – but pre-eminently and profoundly the books and authors that led the way and shaped his life. It's about a family who didn't see the point of reading, and a troubled grandad who taught Mark the power of stories. It's also a story of how writing and reading has changed over the last five decades.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access No One Round Here Reads Tolstoy by Mark Hodkinson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Writing & Presentation Skills. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE

How Did I Get Here?

CHAPTER ONE

A couple of years ago we were moving to a new house on the same estate, round the corner. People often say ‘round the corner’ when it’s really about a mile or so away, past the petrol station, a church, row of shops and a car park of a shut-down pub turned into a hand car wash. But we were literally moving round the corner; Google Maps lists the journey as three minutes on foot and one minute by bike. Too near, then, to make it worthwhile hiring a removal firm. The plan was failsafe: load up the cars a few times with boxes and bin bags while family members and friends lugged the beds, settee, chairs, bookcases, coffee table, drawers and wardrobes through the streets. And we’d start early in the day to minimise the number of witnesses to this meticulously organised if irregular flit.

I had piled hundreds of books onto the bed and was putting them into appropriate boxes, marked in pen: ‘history’, ‘media’, ‘politics’, ‘novels A–C’ and so forth. I looked out of the window. A railway embankment runs parallel to the estate and the line is level with the first floor of the houses, forming a pleasant ribbon of nature. Buddleia, gorse and bramble fight for growing space with the rhododendron, lilac bushes, cow parsley and birch saplings. It was early August. Everything was still, not a leaf shuddered or a stem swayed. When we conjure thoughts of late summer it is light and bright but that day, the day we moved house, the weather was bellyaching between absent and overcast. At least it wasn’t raining.

The house we were buying was being sold by Steve and Steph. Their near-matching names should have been a forewarning. He had extremely smooth and shiny skin for a man in his fifties, as if polished on an hourly basis. She wore a constant grimace that suggested either a recent catastrophic health diagnosis or the loss of a winning lottery ticket. On this designated ‘completion day’ we were in a chain with four other sets of people buying and selling houses. The assorted solicitors had advised that, as contracts had been exchanged on the various properties a few days earlier, completion (i.e. moving out and in) was a formality.

Steve met us at his – soon to be my – front door with a furtive nod. We could put the boxes and bags in the garage, he said. I recognised the implication; it was evident in the set of his shiny unhappy face and perfunctory tone of voice. Behind him, down the hall, was that grimace, cheese-wire tightened to prissiness: tell him, Steve, the garage and no further. She didn’t actually say this but it was easily discerned as she sat perched tight on a wicker chair, arms crossed. I didn’t want confrontation so early in the morning and with so much ahead of us. I did what most people do when faced with a looming predicament: skirted it, hoped it would go away.

Friends turned up and began filling cars with boxes. Soon, they were joined by my parents and two sons, both in their early twenties. Everyone began asking whether they should start carrying round ‘the bigger stuff ’. Judith – the woman buying my house – arrived, followed by more piled-high vehicles and a huge removals van. Within minutes, there were about twenty people in the cul-de-sac. Van and car doors were opened. Items of furniture began appearing on the pavement and in the road. Neighbours joined the throng and little groups were holding discussions, each looking occasionally towards the house, expecting me to appear and make an announcement. This stand-off lasted a couple of long, tense hours. I rang Steve.

‘I’m not at liberty to let you deposit anything in the house until all monies have cleared into our account,’ he said, as if reading from a script.

I told him that everyone else in the chain was moving out and I had a swarm of people outside, restless because they had nothing to do. Steve said I was lucky they had granted access to the garage. I then heard shrieking and wailing and realised it was Steph. I guessed Steve was holding the phone to his chest so I’d not be able to hear, but it didn’t work. He told her to calm down, love, take it easy, darling, he’d deal with the matter. Finally, he informed me that they were about to leave the house and deposit the keys at their solicitor’s office; I’d have to deal with them from here on.

While I’d been on the phone, Judith’s removal team had set about my garden shed, moving my lawnmower, spades and saws onto the street. My heart was thumping, mouth dry, head aching. I had an idea. My sister lived about 200 metres from the house I was buying. She was on holiday but at least we could use her drive and front garden for temporary storage space. I briefed everyone and within minutes a procession formed through the streets carrying my belongings. The experience was unsettling, seeing personal items tucked under arms or held between two people, on show to anyone passing or staring from their houses. Amid the hurry-hurry panic I hadn’t noticed time moving on: it was now mid-afternoon and the estate was beginning to hum with life, people returning from work, kids on their way back from school. One or two did comedy double takes, staring beyond this haphazard train of mattresses and wardrobes as if expecting a film crew to come into view at any minute.

At regular intervals I phoned the solicitor to see if the money had cleared and the keys released. I was told at 4.30 p.m. that it had been received but they were closing at 5 p.m. The office was only five miles away but I had to negotiate rush hour traffic. I got there with minutes to spare. The grumpy lady on reception asked for identification. I didn’t have any; no one had said it was needed. I reasoned with her, asking how plausible it would be that I had randomly walked in twenty-five minutes after someone had phoned and said they’d be there in about twenty-five minutes to collect these specific keys and could also name and describe the vendor (smooth-skinned, shiny, irritating) so accurately.

‘Well, we have to be careful,’ she said, passing them to me, pleased to have the final word.

At last. I was near-euphoric as I drove back, slamming the heel of my hand on the steering wheel in time to the music. As I entered the estate I looked over to the railway embankment. The rows of shrubs were arched, forming shimmering waves. Leaves on the birch trees quivered as if electrified. I knew what this meant. I leaned forward to better see the sky through the windscreen. The blue of earlier had been replaced by a grey slab of cloud. The first few drops of rain fell lonely on the bonnet but quickly built up momentum. I switched on the wipers. I could see the removal party hurrying from my sister’s to the new house, using my belongings to shield themselves from the rain or huddling over electrical equipment to avoid it getting wet.

I parked and entered the house, still fearful of finding Steve and Steph in situ. They had gone, of course. As people funnelled through out of the rain, into the hall and on to the various rooms, it felt like a spiritual transference. I was glad it had become instantly noisy and told everyone they could keep their shoes on; Steve had insisted I remove mine when I’d called round to discuss the purchase. (I’ve always found this bothersome; a house is a home, not a temple.) I stood at the doorway directing the human traffic. I looked across to my sister’s. Standing tall in the drive was a wall of cardboard boxes. The rain suddenly intensified and began bouncing from the ground and past my ankles; August shunted to a raincoat afternoon in November.

‘What’s in those boxes?’ I asked.

‘Your books.’

My books. My books? In this rain? Within two or three seconds I had a pile-up of thoughts: how water resistant was your average cardboard box? Some had been sealed with parcel tape – this would keep out the rain for at least a little longer, wouldn’t it? Why hadn’t I put them in those plastic containers with clasp-shut lids? Hardbacks, at least those with laminated covers, would withstand more rain than paperbacks, probably. Maybe I could save a few of them or even most of them – a curled up cover here and there, a bit of staining or pages smelling musty, possibly, but still readable, still recognisably books. What if they were turning to pulp? I dashed with the others to retrieve the boxes.

At that instant, as I straddled the low chain-link fence, I realised what my book collection meant to me. My head was busy, all full up with the moving, the stressing, and so the feeling hit me elsewhere. I’m not sure where exactly but in the middle and all around – whack. I had been forced, for those few seconds, to imagine life without all those books. I had collected them from first learning to read and they had travelled with me through my growing-up years, several relationships and numerous house moves. On any photograph of me taken at home – family groupings; larking about as a teenager; arm around my first girlfriend; amid the beer bottles and vinyl records of a house shared with a pal; beaming smile in my first bought house and then cradling my baby children – the books are behind me or at the side, always there. They are crammed in the MFI unit of my childhood bedroom and then on the mantelpiece of that clothes-strewn house where we played the latest Smiths single before running hard at Friday night. At first, the collection fits on a shelf beneath the mirror and Debbie Harry poster in my bedroom. Later it is in a specially made bookcase with sagging shelves which my dad had to reinforce with blocks of wood. Thereafter, it grows until it takes up alcoves on either side of the fireplace and covers whole walls. Then it flows into more bookcases, some glass-fronted with a key (invariably missing) to fasten shut the doors, others faux Gothic and chunky with acorns and oak leaves chiselled into the wood.

A sudden stabbing contemplation of all these books possibly lost to me does not let loose an eddy of nostalgia or make me rue the money or time spent on the collection. I’m struggling to understand the feeling until, eventually and limpid clear, it comes: it feels close to the ache of bereavement.

It was a false alarm. The cardboard boxes held firm. My library was intact. I’d probably magnified the danger they were in but isn’t this inevitable when you love something dearly and think it might be lost?

During the move my mother had commented a few times, ‘You’re not going to read all these books.’ She has said this regularly over the years but I have good reason to mistrust her when it comes to books, for she be (crack of thunder, clouds parting) a bibliophobe – ‘a person who hates, fears, or distrusts books’. On this occasion, however, I properly heard her for the first time: the statement hit home. Perhaps it was my age or the realisation that this might be my last house move. Either way, a reckoning of sorts.

I counted the boxes. There were more than eighty. If they each contained, say, forty books, that would make a total of 3,200, and already dotted around the new house (by the bed, on the coffee table, in my bedroom-office) were piles of newly acquired books, ranging from three or four to nearly twenty. Of the grand total, I had probably read between a quarter and a third but, in some cases, this was more than thirty years ago; a reread was probably in order. I carried on doing the maths. The shortest work of fiction in my collection was The Vigilante by John Steinbeck at about 1,500 words and the longest, Women and Men by Joseph McElroy, at an estimated 775,000. The average novel length was generally accepted to be 90,000 words and non-fiction, 65,000. All told, if my collection was three-quarters fiction and one-quarter non-fiction, and it took two or three days of continuous reading to finish a book of average length, I’d need more than twenty years to read them all, and that’s if I didn’t take time off to sleep, eat and have the occasional sup in the Red Lion.

‘You’re not going to read all these books.’ There it was again. I couldn’t dislodge my mother’s truth. I had succumbed to what Americans call BABLE: Book Accumulation Beyond Life Expectancy. How did I get here? Asked this on a Friday night after a few pints and I’m looking for a chair to stand on. Appealing for quiet, please. Amid the chest thuds, quiver in my voice, I’m telling everyone (two pals and the barmaid) that it’s because I’m ambitious and hopeful and ever seeking and each new book bears witness to a restless desire, of wanting, needing more, always more. And, and, if I were to divest myself of these books would I not be conceding that my time on earth is finite and that I’m going to die without reading everything I own? Who of us can defer so meekly to mortality?

Walking home afterwards, too many pints downed, it’s me and the streets and creeping, seeping self-doubt. Listen up, kiddo (you’re always a child to the voice in your head): you’ve only got all these books because you want people to think you’re clever. But you’re not, are you? You’re a CSE-er; always will be. And, admit it, you’re still moping about stuff that happened to you as a kid, which you’re trying to blot out with all these walls of books. You’re not fooling anyone, especially yourself.

The day after, I call on a writer friend (this was an urgent matter, make no mistake). He tells me 3,500 – the latest count – is ‘a lot of books’. The statement is made assertively, as if everyone knows it is an unimpeachable fact.

‘Really?’ I said.

‘Really,’ he echoes, which further implies, I feel, that there is something awry, pitiful even, about a man owning so many books.

As the hangover began to fade, I defended stoutly ...

Table of contents

- Preface

- Part One: How Did I Get Here?

- Part Two: Where Am I Going?

- Afterword

- Appendices

- Acknowledgements