![]()

Chapter 1

Voicing an identity

‘May I always be a credit to my race.’1

Why Brewster and Talawa?

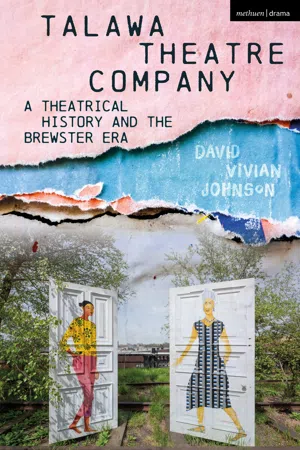

This book is the first detailed history of Talawa Theatre Company under its co-founder and first artistic director Dr Yvonne Brewster OBE. Following a detailed contextualization of theatre history in the opening chapters, the period between 1986 and 2001 is discussed. This is Talawa’s foundation era, during which Brewster started, developed and gracefully began to bow out of the company. Along with Brewster’s contribution to the history of black British theatre, both prior to and through her work with Talawa, the origins of the company, its key early productions and Brewster’s ability to develop and question notions of black British identity through her work are examined. This is a celebratory, though tough journey that marks Brewster’s pioneering legacy in helping to forge the identity of contemporary black British theatre.

Whilst there have been a number of academic books that discuss black theatre and Brewster specifically, most offer only an excellent glance at both. This is seen in Duggan and Ukaegbu’s Reverberations Across Small-Scale British Theatre, Godiwala’s Alternatives Within the Mainstream: British Black and Asian Theatres, and Saunders’s British Theatre Companies 1980–1994. Each honours Talawa’s work by dedicating a full chapter to it.2 Others have focused on plays and playwrights, as seen in Goddard’s Contemporary Black British Playwrights: Margins to Mainstream.3 Others still have produced comprehensive histories. Chambers’s Black and Asian Theatre in Britain: A History provides impressive detail spanning the thirteenth to twenty-first centuries.4 Such writing highlights the need for individuals and specific companies to be examined in greater detail.

African-Caribbean artists in Britain have produced a body of work that merits its own analysis. It constitutes a substantial contribution to British theatre and need no longer be included in, for example, Asian theatre. Whilst the lumping together of huge bodies of work serves a need, it also generalizes, dilutes and sometimes reduces the work of a formidable artist to part of a list, or a footnote. It is often the wider mainstream and funding bodies that necessarily force culturally different groups into the same non-white category in order to more ‘conveniently’ deal with them as a single unit. In fact, these groups are usually more different than they are alike and they do not develop a tangible commonality by being bound in this way, except to those who create the categories. In reality, they remain marginalized and ‘other’. Brewster explains why Tara Arts, for example, cannot be a black theatre company, but why it is associated with others that are: ‘They are Asian and they are Asian-culture-based, this BAME business. I call it BLAME. Just blame everybody else for everything.’5

The central aim here is to avoid the BLAME game and provide a detailed theatrical history for, and highlight the work of, Brewster and Talawa. Anthologies and compilations that include both also often highlight the work of other female and black directors, many of whom merit having their individual story told. Writers and other artists will focus their energies on those they wish to illuminate. This was seen when West Africans felt that Caribbean theatre dominated the black British theatre landscape and founded Tiata Fahodzi in 1997: ‘it became the company’s central mission statement to produce work that emanated from West Africans for West Africans in West African bubbles of London.’6 Their aim was to tell their particular stories in their specific voices, just as Brewster did for her communities through Talawa.

Brewster was born in Jamaica in 1938. This was the year before Hattie McDaniel starred as Mammy in Gone with The Wind and sixteen months before McDaniel became the first African American woman to win an Oscar for best supporting actress for her portrayal of Mammy. Being the only guest in her segregated seat at the Oscars, McDaniel was acutely aware that her win was a huge accolade for the entire black diaspora.7 The seemingly tenuous link between Brewster’s birth and McDaniel’s win is much less spurious when the irregularity with which black life is generally celebrated is considered. Brewster’s birth, unremarkable in itself, becomes significant when looking at her life’s work. What chance was there that a black woman born in Jamaica at that time, even if from a privileged background, would have a notable impact on British theatre? Brewster achieved this because she was unable to live up to stereotypes and was skilled at carving out her own path and identity in equal measure. Mahone comments, ‘The very act of a black woman telling her story, speaking her truth, can be perceived as an act of resistance to oppression; the real power in her exercise of artistic freedom is casting her own image of her own hand.’8

Brewster’s work cast a clear image of black identity that could not fail to resonate with those African, Caribbean and black British people whose stories it told, in their own spoken and non-spoken language forms. It was also a catalyst for many performers who would not have been given the same welcome, opportunity, experience and sense of self from the mainstream. Most importantly, Brewster’s theatre exposed the identity of Britain’s marginalized black communities to the white space, whilst legitimately illustrating the widest possible range of performance styles indigenous to the genre of black British theatre.

Defining black in Britain

Brewster and her work at Talawa are analysed here through the prism of black identity in Britain. Since their first encounters with white people, black people have been redefined by them. The free black people of Africa were renamed slaves, niggers, coons and darkies. Then followed the array of words to label anyone that was mixed, including sambo, mulatto, mestizo, mixed-blood, coloured, half-caste, Creole and quadroon. Contemporary branding now justifies the terms mixed, mixed race, multiracial, biracial, multiethnic and polyethnic. Here, ‘black’ refers to African-Caribbean people and their British descendants.

The foundations of present-day black Britain and black identity within it began in the 1500s, as there have been black people living and being born in Britain since that time.9 It was, however, after Britain had been bombed in the Second World War and needed to be rebuilt that the arrival of black British invitees from the colonies darkened the complexion of British society.

When the Empire Windrush docked in Tilbury in 1948 with 492 Jamaicans, they were welcomed as ‘Five Hundred Pairs of Willing Hands’.10 This, along with the arrivals that followed in the ensuing decade, gives an impression that most Caribbean people arriving at this time came in this way, as skilled non-professionals seeking work in the ‘Motherland’.11 Many had been enticed by the promise of secure well-paid work and educational opportunities. These opportunities saw them taking up posts on London transport and in nursing.12 They were British, they ‘took their British citizenship seriously, and many regarded themselves not as strangers, but as kinds of Englishmen’.13 This status was, however, disputed by the likes of Enoch Powell: ‘The West Indian does not by being born in England become an Englishman. In law he becomes a United Kingdom Citizen by birth; in fact he is a West Indian or an Asian still.’14

Powell’s notion was voiced at a time when those who were later defined by British society as the first generation of black Britons were babies. Whilst the West Indian parents of these children often saw their offspring as British, their children were not always treated as equal to their white counterparts. In keeping with Powell’s above notion of suggested difference these children were made to feel as foreign as their parents had, particularly in the key areas of education and later in employment and housing.15

Such discrimination encourages questions around the complex cultural identity of later generations of black Britons. For them, seldom accepted as British and always having to explain their cultural heritage, the question ‘No, I mean where do you really come from?’ encourages a sense that the ‘black’ in ‘black Briton’ is synonymous with unequal. This has a two-pronged effect: some black Britons reject their Britishness whilst others are firm in their knowledge that Britain is their home and they are here to stay. To affirm the latter and encourage other black Britons to recognize their British roots, the documentation and publicizing of black contribution in all areas of British life must be acknowledged.

Brewster’s work at Talawa ensured that black people saw themselves, along with all aspects of black life, on stage. The questions of race, racism, belonging, forging and articulating an identity in a new place were raised both directly and indirectly through character, plot and production. Along with the topical issues performed was the language they were presented in. Black language forms were used as a device to forge the identity of complex characters, and illustrate how black identity is intrinsically linked to language.

Defining voice

‘Voice is me, it is my way of being me in my going out from myself.’16

The sociolinguistic theories used to discuss language use, as it relates to black identity in Talawa’s productions, fall under the sociology of language and language style as audience design and related theories.

The sociology of language

Joshua A. Fishman’s theory of the sociology of language is used as an umbrella term referring to all aspects of language linked with language behaviour and the responses to it. It examines the characteristics of language varieties, their functions and those that speak them.17 Within the general theory of the sociology of language is the theory of the dynamic sociology of language. This is used to explain selective language change within a single community for different events, and examines both the factors that led to this change and the responses to it. The dynamic sociology of language further encompasses three sociolinguistic concepts used throughout this book when discussing Talawa’s performances. These are overt language, verbal repertoire and antilanguage speech.

Overt language shows how speech forms at risk of dying out are given a higher status to help revive them. In the case of Caribbean and other related speech forms, overt language behaviour is demonstrated in the publication of Caribbean language texts and by performance artists using Caribbean language in their work. Talawa’s African and Caribbean productions illustrate this linguistic reclamation and show that Brewster made a concerted effort to connect language with black British identity, thus exemplifying what Maggie Inchley describes as ‘cultural audibility’.18

Verbal repertoire is the language of a community that uses many forms of speech.19 The speaker decides which speech form is most appropriate for a particular occasion. This dexterity is in continual development am...