![]()

1

“I Remember You”: Stories from Merseyside

Only a few people ever have a front row to history. Carol Johnson is one of them. In 1961, she was fifteen years old and newly employed with a company in Liverpool’s city center. With her office in nearby Lord Street, she and her girlfriends would race to the Cavern Club at lunchtime to ensure the best seats possible to see the Beatles. Carol sat in front of John Lennon—her favorite member of the band—while her friend Margaret, “who was mad on George,” arranged a similarly desirable vantage point. Likewise, other friends sat near their preferred Beatle. While Carol liked other Merseybeat bands that played there, she became a regular at the Cavern because of the Beatles. In her words, “for about two years they were my life.”1 That teenage girls like Carol flocked to this damp, underground venue to hear one of the city’s most popular rock ’n’ roll bands has long been both the stuff of legend and wonder among anyone interested in the Beatles story. For the young women who were there, being part of this exciting music scene not only offered exposure to charismatic performers and a new soundscape, but it also allowed them to be full participants and co-creators of it.

The Beatles’ early years are closely associated with the Cavern, the grotto-like club in Mathew Street where the band played nearly three hundred times between 1961 and 1963. However, this history encompasses other locations around greater Liverpool that also helped establish the band’s local fan base. Second only to the Cavern in its significance was the Casbah Coffee Club, located in the suburb of West Derby. Though the group was still missing a permanent drummer, an early lineup of John Lennon, Paul McCartney, and George Harrison became the Casbah’s house band after performing there for its opening night on August 29, 1959. This appearance was so early in the group’s formation that they were still known as the Quarrymen.2 Soon, other venues across the city like the Aintree Institute and Litherland Town Hall proved important spaces for growing their audience.3 In August 1960, with drummer Pete Best joining the group, the Beatles traveled overseas to Hamburg to begin the first of what, by late 1962, would amount to five musical residencies in the German port city. Nonetheless, most accounts of the Beatles’ early years remain entwined with the Cavern Club and its young patrons. It was where the group played more than anywhere else starting in February 1961. It was also an increasingly popular venue with teenagers, those who helped the Beatles become stars of the local music scene. Fans who followed the Beatles between 1961 and 1963 also witnessed important changes to the group’s membership. Bassist Stuart Sutcliffe left the band in July 1961 and drummer Pete Best was replaced by Ringo Starr in August 1962. Sutcliffe’s departure permanently transformed the Beatles’ into a foursome, with Paul McCartney becoming the group’s bassist, while Starr’s recruitment paralleled the Beatles’ shift from a popular Liverpool band to a national phenomenon.4

Throughout these formative years, Carol Johnson was one of a growing number of female fans who became central to the Beatles’ success. While it would be wholly inaccurate to say the Beatles’ male followers had nothing to do with the band’s rise to local acclaim, the girl fans’ dedicated exuberance was absolutely essential to it. In recalling the many hours spent at the Cavern watching the Beatles, Carol said with a laugh, “I think there were blokes interested in their music, but we never saw them.”5 Her comment speaks to the way in which the band’s most devoted female fans were totally focused on the Beatles while at the Cavern and how young women, as a fully participatory audience, commanded that social and musical space.6 Noted Merseybeat and Beatles authority Spencer Leigh recounts how “the seats at the front of the stage were invariably filled by girls” and that boys were not necessarily welcome there. He shares that “a brave lad” attending the Beatles’ last Cavern performance on August 3, 1963, “got a seat on the front row” only to be met by withering glances from the girls seated there.7

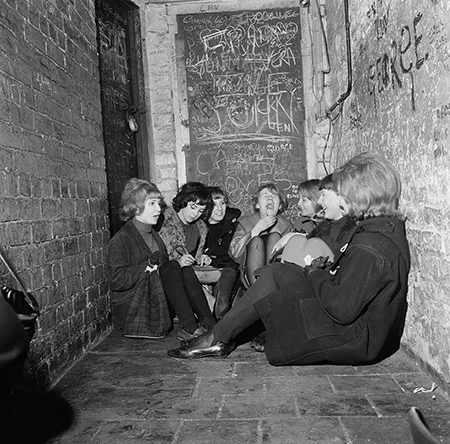

Both Leigh’s account and Johnson’s testimony are matched visually by numerous images which document the Beatles’ Cavern concerts. On August 22, 1962, Granada TV captured the Beatles performing their cover of Lieber, Stoller, and Barrett’s “Some Other Guy” at the club.8 Footage of the audience shows how their female fans were always right there—tapping their feet, swaying to the music, and staring up at the band—whether crowded under the arches at either side of the stage or taking up the first several rows of seats. Girls often waited outside the Cavern long before it opened or outside other venues where the Beatles performed (Figure 1.1). Another telling set of images were shot by photographer Michael Ward on February 1, 1963. Taken in conjunction with a promotional event at one of Brian Epstein’s North End Music Stores (NEMS), they include two of Paul McCartney and George Harrison happily interacting with fans and another of McCartney chatting with three girls as they walk down a Liverpool street—likely after leaving the store. Whether at the Cavern or out and about in the city, getting as close as possible to the band was an essential fan experience. It was this first group of local devotees that established how well the Beatles—both as musicians and as a group of individuals—could relate to young women.9

Figure 1.1 Beatles fans sit in a Liverpool alley waiting for their heroes, 1963. Photo by John Pratt. Reprinted with permission from Keystone Features/Getty Images—Hulton Archive.

The Beatles’ Liverpool history not only is distinctive in how close the band members and their female fans would come to feel with each other, but also demonstrates the down-to-earth normalcy of their interactions. Tony Barrow, the Beatles’ first press officer, observed: “There was a very intimate relationship in Liverpool between the Beatles and their fans. And the Beatles’ fans could actually ring the Beatles. I mean, you just had to look under ‘Mc’ in the phonebook and ring Paul McCartney and say, ‘Please will you play “Some Other Guy” for us at the Cavern on Friday.’”10 Just as Beatlemania, due to its sheer global scale, would necessitate more detachment and depersonalization between the group and its fans, this early period in Liverpool instead emphasized closeness, community, and sociality. Being part of Liverpool’s local music scene was the only time in the Beatles’ career when this feeling of connection was grounded in a tight-knit community. From familiarity to a touch of the familial, it was on more than one occasion that girl fans decided to stop by band members’ family homes. Though the Beatle in question was often not there, it was not unusual for George Harrison’s mother Louise or Paul McCartney’s father Jim to kindly welcome the girls inside for tea and conversation.11 Being part of this growing community around the Beatles also inspired young women to think about how they could further contribute to it. A few decided they wanted to pursue music. This includes the Liverbirds—one of the very first all-female rock bands—and Cavern coat check girl and aspiring singer Priscilla White, who was friendly with the Beatles and eventually shared in Brian Epstein’s management. She would go on to have a string of pop hits starting in October 1963 as Cilla Black.12 While these female pioneers will be discussed again in Chapter 4, it is necessary to introduce them here as dynamic members of Liverpool’s music scene.

In examining this specific social context, which predates and differs from the Beatlemania era (1963–66), it is important to consider what it was about the Beatles at this time—as both musicians and local personalities—that inspired such energy, interest, and creativity among the teenage girls who first dominated their audiences. Barbara Bradby suggests that the Beatles’ cover versions of romantic pop and soul ballads alongside girl group hits positioned them lyrically as male performers who were more self-aware in how they hailed and included young, female listeners. Jacqueline Warwick, meanwhile, contends that girl group covers helped the Beatles “create versions of masculinity centered around transgressive earthiness or adorable approachability.”13 These are convincing claims. However, they also raise further questions about how these sensibilities came to be. The Beatles’ earliest experiences with women help to provide some answers. While many journalists and scholars have tried to understand how the relationship each Beatle had with their mother influenced their musical journey, little if anything has been said about how this may have played a role in how they interacted with their earliest female fans. Arguably, the rapport they established with these Liverpool girls set a precedent for how well the Beatles would reverberate with females around the world. It is also worth examining how the group, as the main attraction within Liverpool’s Merseybeat music scene, helped motivate young women to more confidently navigate, traverse, and inhabit urban, public spaces than Liverpudlian girls of generations past.

Finally, this exploration of the Beatles’ early history as a local, Liverpool band that greatly appealed to women also benefits from one significant addition. For the many Beatles fans who could not be part of this community—those from the advent of British Beatlemania onward—traveling to Liverpool has become a way to engage with the city as a veritable “Fifth Beatle.”14 Merseyside has come to serve as a proxy for the Beatles themselves. Studying the band’s Liverpool origins, fan pilgrimages there since as early as autumn 1963 have created a new afterword to this story. Though the intimacy that local audiences had with the Beatles in the early 1960s can never be recreated, visiting the group’s hometown has allowed latter-day fans to feel a closer connection to a band that, paradoxically, has been absent from Liverpool for close to sixty years. It is their opportunity for a “front-row seat at the Cavern.”

“Stand by Me”: The Beatles’ Fan-Friends

Mark Lewisohn’s Tune In (2013) is a lavish account of the Beatles and its band members’ early lives. The book ends on December 31, 1962—just as the group is about to ring in the year that will lead them to fortune and fame. As a youth culture historian especially interested in girls’ experiences within subcultures and music scenes, what immediately struck me upon first reading the book was Lewisohn’s attention to the acquaintanceships and friendships that developed between the Beatles and their local, female fans. It is the first such historic account to substantially document young women who knew the Beatles and were active members of the Merseybeat scene.15 The testimony Lewisohn includes speaks to the diversity of these relationships. Though it is true that band members dated some of these fans—and drummers Pete Best and Ringo Starr even met their wives at the Cavern—such experiences did not define band-fan relations during this time.16 As John Lennon stated in a mid-sixties interview, “The Cavern girls weren’t fans, not to us, they were friends.”17 In this sense, the girls who enjoyed the Beatles as a local band, and got to know them as people, might be better described as “fan-friends.”

This type of fan was possible in Liverpool because the Beatles performed at venues that lent themselves well to this level of intimacy. And, certainly, they were not yet celebrities. Until the national release of their first single, “Love Me Do” in October 1962, they were simply local personalities. Studies of fandom—today’s online connectivity notwithstanding—discuss the social distance that exists between celebrities and their audiences. Within such asymmetrical, parasocial relationships, the ultimate desire among many fans is meeting their heroes and, potentially, developing actual relationships with them. In the context of Beatlemania, the lengths that some fans would go to in order to meet the Beatles included everything from storming police barricades to sneaking into multistory hotels—sometimes even scaling these buildings to try reaching them. This behavior, closely followed by the media, would inform many people’s perceptions of Beatlemania and led to the stereotyping of these mostly female fans.18

While international renown usually dictates a clear separation between celebrity and fan—with mediated content serving as a poor and partial substitute for face-to-face encounters—local music scenes are predicated upon community and interpersonal communication. The nature of such scenes means that a band’s earliest supporters are usually acquaintances, friends, or, at the very least, familiar faces in the crowd.19 Even throughout most of 1962, the Beatles’ name recognition was (apart from Hamburg) primarily regional. As one early fan would recall, “[The Beatles] weren’t famous in Liverpool for being ‘famous.’”20 Instead, they were liked and respected as a popular Liverpool band comprised of approachable local “lads.” Access to the group was facilitated by the venues where they performed. These clubs and halls did not have well-defined “backstage” areas, which helped blur the division between band and audience. In the case of the Casbah, the club was owned and operated by drummer Pete Best’s mother, so it was also a hang-out space for the Beatles when not performing. The Cavern, meanwhile, had a “band room” for musicians to prepare for their shows, but it was very small and due to the club’s layout, patrons often walked past it. This made it easy for fans to speak with the Beatles before, in between, or after their sets.21

By frequenting the Beatles’ Cavern gigs or regularly attending other shows around the city, female fans established connections with the Beatles that manifested in a number of ways. It could be a chat with a band member either at the Cavern’s snack bar or in the tiny band room. Some more personal meetups took place at various venues around the city—whether at the hip Jacaranda coffee bar, the Blue Angel nightclub, or at the Grapes, the pub just across from the unlicensed Cavern. As recounted in Mark Lewisohn’s Tune In, when the Beatles traveled back to Hamburg for a series of shows in 1962, several girls corresponded with band members—something the Beatles themselves had requested and encouraged. The group feared the momentum (and fan base) they had built up would diminish while in West Germany. Recognizing that personalization would matter, John, Paul, and George’s letters to these teenagers often arrived tucked into specially decorated envelopes.22 It is not clear whether the same kind of correspondence took place between the Beatles and any of their male fans, but it seems unlikely.

In these early years, it was easy for the Beatles and their fans to communicate with each other. During their lunchtime performances at the Cavern, band members spoke directly to the audience and asked for song requests. Mary McGlory and Sylvia Saunders, fans who soon became the bassist and drummer for the Liverbirds, shared with me that these performances “felt as though friends of yours were playing just for you.”23 Another fan remembers that “if they recognized people [in the audience] they would wave to them.”24 Girls in the front row may have calmly stated their song requests, but titles like “Besamo Mucho” or “Stand by Me” were sometimes shouted across the club or written on pieces of paper handed to John or Paul. Sometimes this interaction was extended to conversations that took place beyond the context of the Cavern. Margaret Hunt, who first saw the Beatles perform at the Aintree Institute, decided to look up Paul McCartney’s home phone number and call him. Still asleep when she rang one weekday morning, a message was left for him. Much to her surprise, the call was returned. This first pleasant, one-on-one interaction with McCartney led to several o...