![]()

1 Okinawa and Japan

1.1 Introduction

I first learned about Nenes (Nēnēzu) in 1993, when they appeared on the front page of Folk Roots magazine (Figure 1.1). The eye-catching image showed four cheerful-looking female singers dressed in colorful Okinawan costume. Although not released internationally, their album, Koza Dabasa (That’s Koza, 1994: Appendix 1)1 was critically acclaimed in the world music scene. As a music researcher working in the anthropology of music, I found Nenes particularly inviting, as they blended Okinawan folk music styles and instrumentation with the sounds of contemporary popular music—a hybrid sound that combined familiarity with dissimilarity in musical style. Koza Dabasa was laced with a sense of difference from Japan’s southernmost prefecture, whose music and language were markedly dissimilar from anything I had heard in Japan’s four largest islands of Honshū, Hokkaidō, Kyūshū, and Shikoku (which Okinawans refer to as Yamato), and the album blended further cultural differences by including guest appearances of famous US musicians. A further attraction was the central figure of China Sadao (b. 1945), a well-known Okinawan folk performer who was writing songs, playing sanshin (three-string lute), managing, and producing the group. I didn’t get to experience their live sound until 2003, and by that time, their lineup had entirely changed; they were performing regularly in the touristic live-house scene in Okinawa, and they had toured Europe and appeared at a UK WOMAD festival (World of Music, Arts, and Dance). Even though Nenes are not mainstream in Japanese popular music, they have created and maintained a distinct and recognized space in the Okinawan music scene that blends traditional and contemporary musical styles. What makes Nenes especially interesting are the complex ways in which they have established a musical identity in Okinawa and negotiated a place in Japan and beyond with their hybrid sound and exotic image.

Figure 1.1 Folk Roots front cover (1993, v.123). Courtesy of Ian A. Anderson and fRoots.

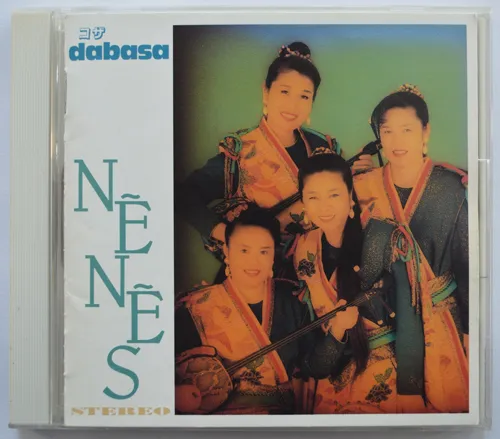

Nenes were put together in 1990 by the male Okinawan folk musician, China Sadao. Nēnē means “elder sister”2 in Okinawan, and the “s” (pronounced “zu”) added at the end of the word turns the group’s name into an English plural, a form which Japanese nouns do not have.3 Nenes’ first album, Ikawū (Going, 1991),4 was pivotal in launching the group’s first ten years of local, national, and international performing and recording—a period which coincided with the so-called Okinawa boom years of the 1990s, which witnessed a popularization of Okinawan culture across Japan (Mansfield 2015). At the time, Ikawū was the best-selling Okinawan album (Fisher 1999) and offered a significant foundation to their music style. Nonetheless, popular music critic Paul Fisher (1999) has noted, “Nenes were probably at its peak with the 1994 album ‘Koza Dabasa.’” Reaching number 62 on the Japanese Oricon charts (their highest ranking) with sales of 1.3 million units (Oricon 1999: 112), and critically acclaimed as their “most adventurous and successful” album (Potter 2010: 86), Koza Dabasa (Figure 1.2) is not only an expression of Okinawan musical identity of the 1990s but also an example of cultural hybridity that features an eclecticism of performers, instruments, and sounds.5 In Okinawa, such blending is expressed through the local notion of chanpurū (mixed), which, in the case of Nenes’ music, is the result of globalization and the localization of diverse sounds and cultural influences. The notion is extended through other cultural flows, including the recording of the album in several national and international locations (Osaka, Okinawa, and Los Angeles), its release on Ki/oon (a subsidiary of Sony Music Entertainment), and its featuring of several internationally celebrated guest musicians who came together to help make this world music release. Koza Dabasa’s musical style mixes local Okinawan instruments, folk songs, and vocal techniques with the sounds of popular music, producing a sonic hybridity that reflects a confluence of cultural elements that are characteristic of Okinawa itself when compared to many other parts of Japan. A study of this album provides a window into Okinawa’s history, culture, and music, as well as some of the ways that exoticism is presented, communicated, and contested in the world music industry.

Figure 1.2 Koza Dabasa album cover (1994). Courtesy of Sony Music Direct.

While Okinawa is home to many pop artists that play the sounds of J-Pop (Japanese popular music) and localized global music styles—the famous ones include Amuro Namie (b. 1977), Mongol800 (1998–), and Orange Range (2001–)—Okinawa’s musical traditions also include instruments, sounds, and poetic forms that are sometimes distinct from other parts of Japan. These hallmarks of local musical identity are based on the elements of traditional music that are maintained in the present day. These culturally distinctive elements include the sanshin, shima-uta (island [folk] song, see Section 4.4, Chapter 4), vocal styles, shima kutuba (island speech, i.e., community languages of the Ryūkyū Islands), and local musical scales (Chapter 2). Such local features are nowadays frequently blended with the broader elements of global popular music in what might be termed neo-traditional popular music, or, in Okinawa, as Uchinā pop (Okinawan pop; Tenkū Kikaku 1992),6 thereby helping to sustain Okinawan traditions in transformative ways and offering a new type of Japanese world music for local, national, and global markets. While such hybridity is typical of global pop (Taylor 1997) and the world music scene more broadly, music in Okinawa is produced and consumed in ways that add to cultural meaning—as an expression of Okinawan identity and ethnicity (including language); as an internal Japanese Other in a geo-cultural binary between Okinawa and Yamato; and as a product of the world music industry.7 In each of these spheres, Okinawa is often presented as exotic, a key element of cultural (self-)representation.

Nenes have been performing and releasing albums since 1991 (Appendices 2–3). The four original singers were already established shima-uta performers and brought to the group much prior knowledge of traditional Okinawan music and skills in performing musical instruments such as the sanshin. Such was Nenes’ success that they went on to represent Okinawa at international festivals, concerts, and tours, and recorded with international artists such as British-Indian Asian Underground performer Talvin Singh (b. 1970). Nenes were the first all-female Okinawan group to achieve such widespread national and international recognition. China Sadao established a live house (venue for live music) where Nenes could provide regular musical entertainment in the Okinawan touristic setting, at first in 1994 in Ginowan City and from 2007 moving to Okinawa’s capital, Naha City. The success of the original group peaked with Koza Dabasa, and since that time, the group has reinvented themselves several times with a number of different lineups (Appendix 4). However, the group has been constant in blending traditional and popular forms through three decades, which has seen their popularity and cultural role change in response to different trends and influences.

1.2 Cultural Background

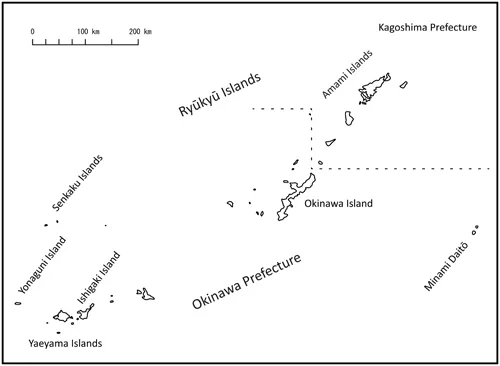

The term “Okinawa” has several geographic meanings. Imposed on the region during late-nineteenth-century Japanese colonialism as an alternative to Ryūkyū in the years following the end of the Ryūkyū Kingdom (Smits 2019: 10), Okinawa defines a Japanese prefecture (Okinawa-ken), an island (Okinawa-hontō), and a city (Okinawa-shi). In this book, “Okinawa” refers to the prefecture, with specific locations described as required. What characterizes the prefecture is its island and archipelago: its largest island (Okinawa Island) is the fifth largest island in Japan after Honshū, Hokkaidō, Kyūshū, and Shikoku; in addition, the prefecture has a number of smaller islands and archipelagos, with a total of 160 islands of which thirty-nine are populated (Okinawa Prefecture Department of Commerce 2019).8

Okinawa is geographically distant and distinct from Japan’s four largest islands and the nation’s capital (Figures 1.3 and 1.4). All of Japan’s other prefectures lie primarily on these islands, although many have offshore islands.9 Okinawa Island has the largest population and includes Naha City.10 Located in the southwest of Japan in the southern part of the Nansei Islands, and with a subtropical climate, Okinawa is geographically far away from Yamato: Naha is 1,687 km (about 1,000 miles) from Tokyo. In fact, it is closer to Taiwan (640 km from Taipei) than it is from the southernmost main Japanese island of Kyūshū (758 km from Kagoshima City).11 Some smaller Okinawan islands are actually closer to Taiwan than to Okinawa Island (i.e., Yonaguni Island in the Yaeyama archipelago), and the Senkaku Islands are contested politically with the People’s Republic of China and Taiwan.

Figure 1.3 Japan. Edited copy of a map by Free Vector Maps, http://freevectormaps.com.

Figure 1.4 Okinawa Prefecture and part of Kagoshima Prefecture. Edited copy of a map by 3kaku-K, http://www.freemap.jp.

This geographic distance has given Okinawa a distinct cultural and political history. The region of present-day Okinawa Prefecture and many small islands to its north (nowadays part of Kagoshima Prefecture) was the Ryūkyū Kingdom, understood to have formed in 1429 from the unification of three kingdoms.12 This kingdom was positioned between Yamato (Japan) and China. It had, and Okinawa continues to have, its own cultural identity, with distinct languages, dialects, clothing, and music. In 1609, the Satsuma Domain (Satsuma-han) of southern Kyūshū invaded it and made it a vassal state.13 However, Ryūkyū was positioned as independent and maintained links with both Satsuma and China, receiving investiture from the Ming dynasty (1368–1644) and paying tribute to it (Yuan 2013: 132). Following the Meiji Restoration in 1868, Okinawa spent a short period as the Ryūkyū Domain (Ryūkyū-han, 1872–9) before Japan annexed it in 1879 and made it a prefecture during an era of national expansion and colonialism, which was both contested and welcomed by different groups in Okinawa (Smits 2015).

The Japanese state thereafter practiced a policy of forced assimilation (Kerr 2000: 420–58), which was also harshly imposed on the indigenous Ainu people of northern Japan as political borders expanded in that direction too. With an institutionalized assimilation policy (dōka seisaku) imposed by the Japanese government beginning in the Meiji Era (1868–1912), local traditions were sometimes suppressed, migration from Yamato was widespread, and acceptance of the Japanese language, the Emperor, and Shintō (Japan’s nationalized indigenous belief system) was forced on the population. Regardless of the degree to which Okinawans mastered an idealized Japanese cultural identity, they often faced prejudice at home and in urban Japanese labor markets on the “mainland” (i.e., Japan’s four largest islands).14 For example, in the late Meiji Era, cultural oppression was evident in schools, where “a student who was caught speaking the local dialect had to wear the so-called hōgen fuda (dialect tablet) until he or she found another student who had violated the ‘no dialect’ rule” (Meyer 2007: 161–2).

During the Pacific War (1941–5),15 Okinawa was the site of some of the fiercest conflicts: the Battle of Okinawa (1945) saw casualties of over 200,000, of which nearly half were Okinawan civilians (Figal 2001: 65). Okinawans had long suffered discrimination and victimization elsewhere in Japan, and this pattern of abuse continued as the US military occupied Okinawa following the war. Although Okinawa reverted back to Japanese sovereignty in 1972, the islands still host some of the largest US military bases in the Pacific, and crimes by US personnel have stirred public outrage (Inoue 2007). The US occupation of Okinawa had a huge impact on local identity and politics, especially in abrading any sense of not being Japanese, and that influence remains visible today, particularly in terms of the discernible and contested flows of US culture (Chapter 5).

Meanwhile, tourism in Okinawa has grown rapidly since the end of the Pacific War and is nowadays Okinawa’s biggest industry. The number of visitors has nearly doubled since 201...