![]()

Part one

A story of origin

![]()

1

A laiko (popular) song by Tsitsanis (1948)

Vasilis Tsitsanis’s ‘Cloudy Sunday’ was recorded for the first time on 11 August 1948.1 The label on the seventy-eight rpm record states (see Figure 1.1):

Vasilis Tsitsanis

His Master’s Voice, OGA 1396–1, AO 2834

License number 316–14800 (see Censorship Committee)

Prodromos Tsaousakis and Sotiria Bellou

Accompanied by laiki orchestra

V.TS.–AL.G.

The recording consisted of two bouzoukis, a laiki guitar,2 and two singers. This type of orchestra is rather common for the time, even though the mood for reform of the laiko aesthetic from within is tangible:

Figure 1.1 The record label of the original recording of ‘Cloudy Sunday’ (Panagiotis Kounadis archive).

– The command of the vocal lines shared by Tsaousakis and Bellou is more complex in relation to the existing bouzouki-based repertoire.

– The tonality choice initially takes us by surprise. One would expect for a C or a D to be chosen, tonalities used mainly in this type of melodically structured song, due to the fact that they comprise eminently male tones. In addition, the tonalities from B to D constitute the overwhelming majority of Tsitsanis’s song sung by Tsaousakis. What is more, the song was established later in the tonality of D (something that still holds true today). Even so, with the desire for orchestration of the voices on the one hand and the singularity regarding the range of Bellou’s voice on the other, G was chosen,3 in this way dividing the piece in two, the first half being performed by Tsaousakis. In the second half, Bellou takes over and is now in command of the melody.

– The characteristic ornamentation of the instrument constitutes a new proposal that Tsitsanis puts forward, in essence setting up the first bouzouki school in laiki music. The erratic appoggiaturas, his aggressive and crystal-clear pick, and the shifting of melodic time constitute his most characteristic innovations, compared to the up to then tradition.

– The arrangement innovations with the second bouzouki, even though it goes without saying that we see them in previous recordings, mainly by Spyros Peristeris,4 constitute now an established new circumstance that Tsitsanis structures, using oftentimes a third bouzouki in his orchestrations. However, the roles of the instruments are no longer restricted to the trite first-second voice in parallel thirds, but introduce counterpoint dynamics.

There is a great response from the audience towards the song, and its popularity is legendary. A plethora of recordings follow, some by the composer himself and others without his involvement. There is diversity in aesthetics approach, changing, in many cases, a lot of its basic characteristics. This is what happens generally with popular music; the fluidity of its nature is ascertained by its evolution through time, as it is reborn every time through a new rendition, ageing albeit continually refreshed.

The three official recordings of ‘Cloudy Sunday’ by Tsitsanis took place in 1948 and 1959. In the first two recordings, which were both recorded in 1948, Prodromos Tsaousakis and Sotiria Bellou, and Marika Ninou,5 Vasilis Tsitsanis and Ioannis Salasidis sing, respectively. In the first reading, perhaps due to the short time period, these two performances present quite a few similarities. A more thorough study, however, proves the diversity which dominates the spirit of each, which is obviously due to the malleability which characterizes the musical genres that have as their core the orality of a performance. And so, we observe differences in performance tempo, something that has a direct impact on the qualitative characteristics (phrasing, basslines in the accompaniment, bouzouki ornamentation as well as others). Also, the distribution of the sung phrases differs significantly, seeing as three voices participate in the second recording, instead of two as in the first. The third recording, with singers Stelios Kazantzidis, Giota Lydia and Marinela,6 generates even more interest as regards diversity.

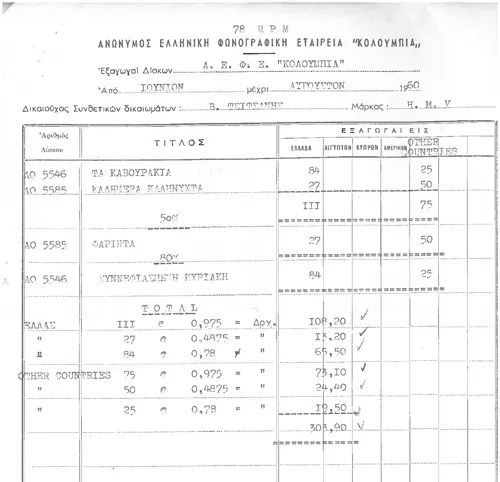

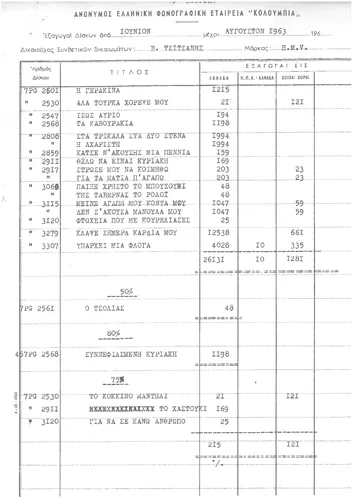

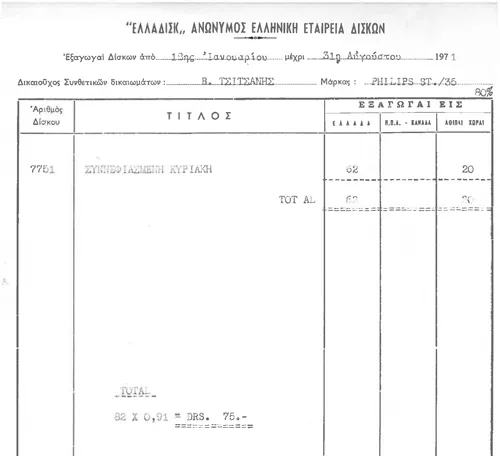

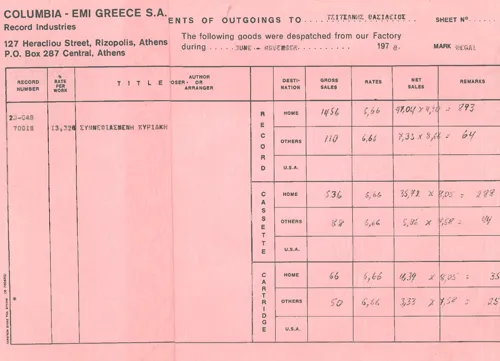

At this point, we must stress the importance of the issue of identifying the songs with the performers, a phenomenon directly linked to popularity which does not concern only the song but a certain performance of the song. In other words, the interpretation of a musical text (which redefines the content, the meaning and the message of the song) will guarantee either popularity or rejection by the audience. In the case of the third performance , Kazantzidis’s rendition overshadows the other voices; thus, they are rarely mentioned. In this particular recording, Kazantzidis presents a sample of his own singing style, which already plays a vital part in the course and development of the urban laiko genre (for Kazantzidis, see Oikonomou, 2015), a style that did not take long to reach the dimensions of a school. Although quite a few of the characteristics of the next period, regarding vocal practice, are perhaps obvious in Ninou’s performance, Kazantzidis emphasizes the leading role that the voice is to now adopt, abandoning the aesthetics of collectivism which we see in the previous stages of urban laiko song.7 For example, he does not adhere to the rhythmic flow that the orchestra constructs, projecting his vocal phrases and preferring, often extremely accented, embellishments on notes of medium and long duration. All the aforementioned are characteristics which prove the versatility of urban laiki music, let alone a song hailed as incredibly popular, something which equals innumerable performances in the per se places of performance of laiki music, that is, the music halls (for a sample of the popularity see the royalties payments in Figures 1.2 to 1.5).

Figure 1.2 Royalties payment receipt which includes ‘Cloudy Sunday’, 1960 (Tsitsanis family archive).

Figure 1.3 Royalties payment receipt which includes ‘Cloudy Sunday’, 1963 (Tsitsanis family archive).

Figure 1.4 Royalties payment receipt which includes ‘Cloudy Sunday’, 1971 (Tsitsanis family archive).

Figure 1.5 Royalties payment receipt which includes ‘Cloudy Sunday’, 1978 (Tsitsanis family archive).

Not only for symbolic but also for practical reasons, Tsitsanis’s first recording shall be used here as a basis, which could be considered as a major point in Greek laiki aesthetic. As a necessity for the present study, this particular first performance was rendered on staff notation, where the recording of the vocal part is accompanied by the rhythmic pattern of the chordal sequence (see Part Four). This musical text was translated8 subsequently into Byzantine notation (παρασημαντική, parasimantikí), so as to facilitate the comparison to the Byzantine hymn.

Notes

1 ‘Cloudy Sunday’ original recording: https://youtu.be/8QroGi1vRuU. By using internet links for a major part of the audiovisual material, the article by Phillip Tagg ‘Why Are Popular Music Studies Excluded from Italian Universities?’ comes to the forefront (2014: footnote 2).

2 The term ‘laiki guitar’ is used by the world of the rebetiko (protagonists and audience) to denote the difference not only in performance practice of the instrument but also in its manufacture.

3 As we shall see further down, the recording teeters between F sharp and G. This concerns issues with the revolution speed of the record. It may be due to the initial etching of the seventy-eight rpm record, but it could also be the result of subsequent conversion into digital form and the by-chance deviations in the rotation of the seventy-eight-rpm record during reproduction. Lastly, it could also be the result of deviations in the reference tone during tuning.

4 Regarding the work and the role of Spyros Peristeris in Greek laiki music, see Ordoulidis (2017b).

5 ‘Cloudy Sunday’: Philips, PE 402036, 1948: https://youtu.be/8nXpxuHVZqs.

6 ‘Cloudy Sunday’: HMV, OGA 2851–AO 5546, 31 March 1959: https://youtu.be/ZG8AiQQrrTc.

7 Regarding the collectivism in rebetiko and laiko, see Ordoulidis (2014: 57–9).

8 In many parts of the book, the term ‘translation’ was preferred instead of the term ‘transcription’, when dealing with the transfer of Byzantine notation to staff notation. This practice was preferred in order to highlight the singularity of the description of a music phenomenon with two so very different writing systems. Since each writing system carries its own idiomatic tendencies, during the transfer of one text to the other, the latter is compelled to imply the idioms of the former, without the ability to describe them accurately. In other words, each writing system, often, also applies specific practices and habits to a musical act which has as its starting point a musical transcription.

![]()

2

A hymn from the Orthodox musical tradition

‘The Akathist Hymn’1 is an original2 kontákio3 and belongs to the hirmologic4 type of Plagal of the Fourth echos.5 Even though ‘Cloudy Sunday’ is associated with ‘The Akathist Hymn’s’ version in the brief type,6 it must be noted that it exists as a slow and a slow-brief7 hirmologic type too. According to the theory of Avraam Euthymiadis, in the hirmologic style ‘every syllable of the words of a lyrical text lasts, usually, one and rarely two or at the most three single beats’ (Euthymiadis, 1972: 345). Generally, the Byzantine pieces of the slow type are characterized by a more complex form, where the same syllable may last for several beats. But also the atmosphere, as a whole, that is cultivated by the slow melody is quite different aesthetically from that of the brief, even though they belong to the same echos.

Even though there are a multitude of manuscripts and transcriptions for ‘The Akathist Hymn’, for the present study those of Ioannis Lambadarios and Stefanos Domestichos (1850)8 and those of Georgios Progakis (1909), which are considered classical by researchers, were chosen. In essence, they are transcriptions of the old form of music notation style to a newer one, as decided by the three-membered Music Committee proposed by the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople in 1814, consisting of Chrysanthos...