![]()

![]()

The standard realist approach aims at describing the world, reality, the way it exists out there, independently of us, observing subjects. But we, subjects, are ourselves part of the world, so the consequent realism should include us in the reality we are describing, so that our realist approach should include us describing ourselves “from the outside,” independently of ourselves, as if we are observing ourselves through inhuman eyes. What this inclusion-of-ourselves amounts to is not naïve realism but something much more uncanny, a radical shift in the subjective attitude by means of which we become strangers to ourselves. (Žižek, Disparities 328–9)

Since the very beginning of his career there has been trouble placing Dickens squarely in the tradition of mimetic characterization in which other Victorian novelists became so deeply entrenched over the course of the century. In fact, in some ways (and especially in terms of character) it is difficult to situate Dickens within the tradition of Victorian realism at all; and this tension between Dickens’s style of representing character and the tenets of realist representation, which became increasingly institutionalized and technologized in forms like portraiture and eventually photography and other means of mechanical reproduction, was not infrequently the source of harsh criticism for Dickens. One response to this tension, for instance, has long been and remains to be to “accuse” Dickens of being a “caricaturist” as opposed to a realist. A central implication of this claim (which is of course typically a means of diminishing or dismissing a certain kind of characterization) is that his characters give us an “external” or even surface or superficial image of character rather than the “innerness” and psychological “depth” valued by mimetic realism. But it is perhaps only Chesterton who, rather than defend Dickens against this claim of being a caricaturist, truly reconsiders and revaluates the term itself:

The common claim that Dickens’s characters are caricatures, we can say, derives largely from his ability to capture “the essence” of a character in “a few strokes,” a few key features uniquely capable of being “profound[ly]” and “powerful[ly]” symbolic, such as verbal tics, bodily gestures, personal mannerisms, or even objects (as in the eternally animated butterflies on Mrs. Markleham’s hat), which are distorted or overdetermined. The “resemblance,” or “essential characteristic” that makes a caricature effective or convincing, is not based on a skill for recreating likeness at all, but on some more elusive understanding or “delicate instinct” of “what part of a thing” captures its identity or its potential for symbolic expression. T. S. Eliot, for example, said that “Dickens’ figures belong to poetry, like figures of Dante or Shakespeare, in that a single phrase, either by them or about them, may be enough to set them wholly before us” (411). Thus we can make an important distinction at this point, and recognize that Dickens’s characters are not, stricto senso, caricatures (aggressively transformed likenesses directed at individuals or types) but are structured on the same nonmimetic principle as caricatures; that is, they are not caricatures in a generic sense, but they share a similar formal aspect of representation, which locates “essence,” or being, not in likeness but in distortion.

The idea of “charging” a particular feature or a particular group of features with the essence of the whole is, as Ernst Kris tells us, inherent in the very word “caricature”: “The Italian caricare and the French charger (charge = caricature) convey the same idea: to charge or overcharge; we would add, with distinctive features. Thus a human countenance may have a single trait accentuated so that the representation is ‘overcharged’ with it” (Kris 174). Mimetic likeness is therefore not the basis for caricatural representation but in fact part of the representation material, an aspect of content not form: caricature is a “playful transformation of [a] likeness,” as Kris puts it (192). Thus instead of mimesis or imitation, Kris sees at the heart of caricature a representational method analogous to that of wit and dreams according to Freud: “The psychologist has no difficulty in defining what the caricaturist has done. He is well acquainted with this double meaning, this transformation, ambiguity, and condensation. It is the primary process used in caricatures in the same way that Freud has demonstrated it to be used in ‘wit’” (196).

Ernst Kris frames his famous essay on caricature (written in collaboration with E. H. Gombrich, though later published separately after some differences of opinion) with the question of why “portrait caricature was not known to the world before the end of the sixteenth century” (189). His answer draws on the now more familiar narrative that, historically, art of the modern era tends to move away from the emphasis on imitation seen in classical art and towards imaginative invention or play. But it also uses this narrative to tap into some less familiar ideas about the image as such, and particularly visual images, that, though only adumbrated here, could be compared with more theoretically nuanced arguments in recent criticism, like that of Garrett Stewart (Between Film and Screen), about the nineteenth-century novel prefiguring the imagistic or specular expressiveness of modern cinema: as Kris puts it, “[t]he work of art is—for the first time in European history—considered as projection of an inner image. It is not its proximity to reality that proves its value but its nearness to the artist’s psychic life” (198–9). As in Chesterton’s comments on caricature (as a means of “profound philosophy and powerful symbolism”), this formulation of modern art (though perhaps a bit schematic) stages an implicit opposition between mimetic representation and artistic vision: “The successful caricature distorts appearances but only for the sake of a deeper truth. In refusing to be satisfied with a slavish ‘photographic’ likeness the artist penetrates to the essence of a person’s character” (Kris 198). For Kris and Gombrich, this “playful transformation of a likeness” appeared so late in the course of the history of the visual arts, as opposed to the linguistic arts, because “the visual image has deeper roots, is more primitive,” and thus to play with visual images presupposed “a degree of security” about the mutual independence of the two orders, representation and reality. This is why “the birth of caricature as an institution marks a conquest of a new dimension of freedom of the human mind, no more, but perhaps no less, than the birth of rational science in the work of Galileo Galilei, the great contemporary of the Carraccis,” who were, according to Kris and Gombrich, history’s first real portrait caricaturists (Kris 202).

While Kris’s conclusions become more difficult to sustain the more literally (including a certain kind of historicity under this label here) one tries to take them, I am suggesting that there is something profoundly useful in his intuition here linking the visual image, in a preconscious way, with the ideological force of mimesis as a means of grounding the “real” in a sense of presence, and representation in simulation, so that distorting, or as it were scarring, the sacred surface of mimesis is perceived as dangerous to the “objective” ground of this reality itself. Whatever historical narrative we do or don’t give it, caricature plays with the opposition between the two realms (representation and the real) in way that specifically haunts the mimetic exhibition of individuality embodied in nineteenth-century portraiture, giving caricature a certain spectral dimension. And we can add here that where mimesis posits a seamless presence in the order of the real reflected in the sense of completeness mimesis generates, caricature opens a Disparity or “bar” within the real itself by maintaining, as I will discuss presently, a certain doubleness or gap in itself and a certain representational materiality of the real: as Agamben puts it, “with apparent frivolity, caricature separated the human figure from its signified; but … only by twisting and altering its proper lineaments could it acquire new emblematic status” (144) and thus “[m]etaphor, caricature, emblem, and fetish point toward that ‘barrier resistant to signification’ in which is guarded the original enigma of every signifying act” (149). In this sense, caricature, as a form of (nonmimetic) representation comparable to dreams and jokes, is disruptive and subversive in a more ontological sense than is generally accepted: it embodies a breakthrough that marks a “new dimension of freedom” from the grasp ideology has over the order of the real.

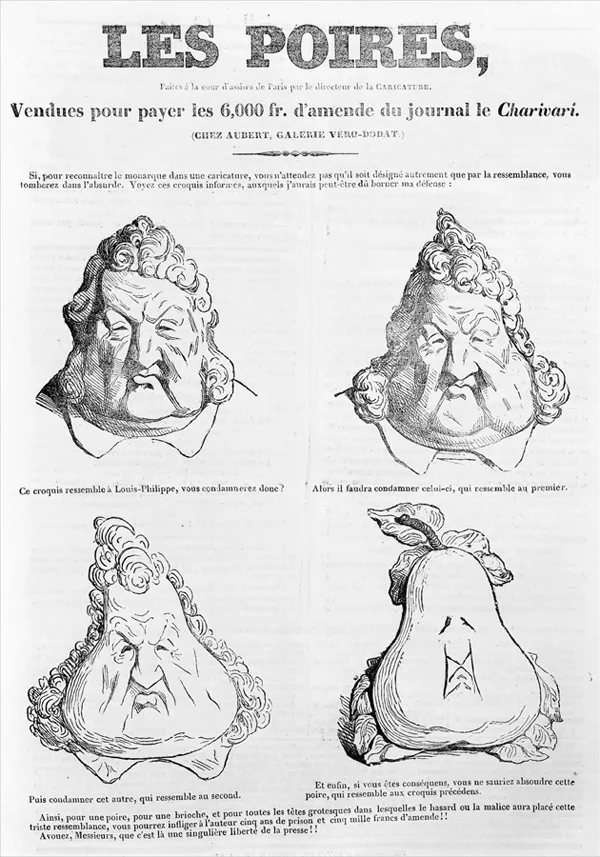

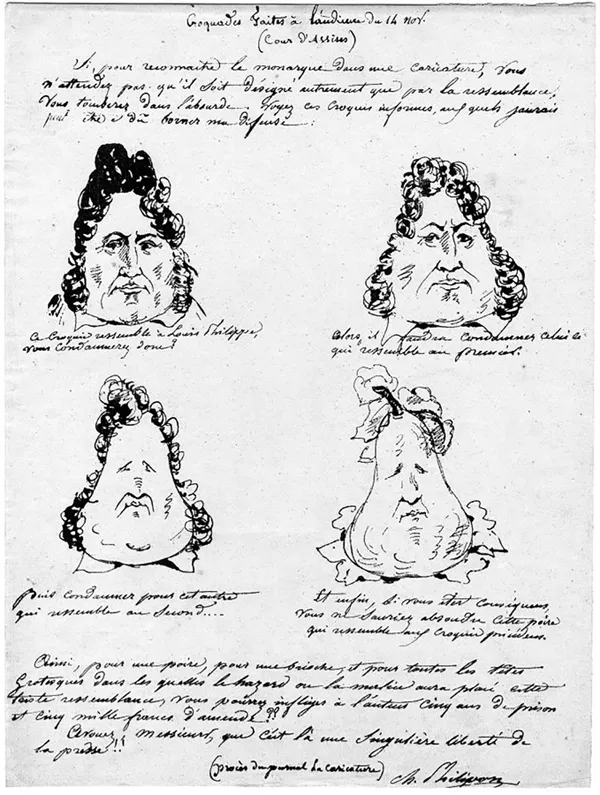

To illustrate this “breakthrough” caricature achieves with respect to the kind of authority the mimetic image holds in the visual sphere, Kris gives the example of “Les Poires,” Charles Philipon’s famous caricature of King Louis-Philippe as a pear (Figure 1).1 This legendary caricature gives us an excellent example of the form’s potential for overdetermination and even captures the process of distortion that allows for its transformation of mimesis into symbolic material. “The Pear” originated in the trial against Philipon who was charged—as well as heavily fined and faced with imprisonment—with slander for claiming Louis-Philippe was a “fat head” (or in the French expression, a “pear”); as the story goes, Philipon sketched it off the cuff to demonstrate to the court the natural relationship between the king and a pear, as if he were merely bearing witness to an objective discovery, as the illustration proved. This partly anecdotal context thus captures well the kind of playful but effective subversion of established law and logic that is latent in the caricatural form as such. Wielded effectively and in the right context, as demonstrated here, caricature can distort the laws of the signifier, so that “conscious logic is out of action, its rules have lost their force” as Kris puts it, revealing a kind of underlying dream logic that rearranges the structure between words and images through a nonmimetic link: here, for instance, “one of the mechanisms now in action [condensation] can cause, as in a dream, two words to become one, or merge two figures into one” (196), so that king and pear become “Les Poires.”

Neither Kris nor Gombrich give a truly detailed visual analysis of “Les Poires,” and in fact both of them seem to attribute it to Philipon alone, whereas it was at first conceived and sketched out by Philipon (Figure 2) but was later refined and executed as a lithograph for La Caricature by Daumier (Figure 1). Yet a close visual analysis of Daumier’s/Philipon’s “Les Poires” would be as good a place as any to begin formulating this idea of a breakthrough in the visual image, not least of all because Kris attributes the subversive and revolutionary power of this image to a kind of cultural return of the repressed that structurally resembles the repetition compulsion of Freud’s uncanny—where magical thoughts that were supposed to be “surmounted” return in objective form—when he says that, “under the surface of fun and play the old image magic is still at work … if the caricature fits, as Philipon’s Poire obviously did, the victim really does become transformed in our eyes” (Kris 199). As is the case with the uncanny, the very affect produced by caricature haunts us with our own spectrality: we imagine the real king differently after seeing this caricature because, after all and despite our own logical “knowledge,” we can’t dismiss the image as merely a neutral copy detached from the real person, or shake a belief in the image’s ability to transgress that strict opposition. Indeed, the idea of “image magic” here can thus be thought of in terms, again like the uncanny, of an approach to the desubjectifying Real that transgresses the reality/representation and internal/external oppositions. I will develop the onto-political aspect of this idea in the next chapter in relation to the revolutionary and polysemic nature of effigy, but here it is important to note the revolutionary nature of the caricatures themselves as developed by the French lithographic caricaturists of the 1830s and 1840s: these images not only represent revolutionary views in content, they were the focal point of a kind of antagonism inherent to representation. Philipon, Daumier, and others were fined, and even sentenced to imprisonment, for caricatures they published in Philipon’s two publications, Caricature and Charivari. This creative explosion of caricature as an art form, so fertile for the developments in the visual arts throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, was engendered in Paris in the 1830s and 1840s as part of a brand new medium, the first illustrated journals to use lithography to mass produce images—images that were at once darker and more playfully nuanced and tonal than most previous forms of production allowed for. The lithographic image lent itself to distortion, visual play, and reproduction in a way that etching and engraving at this scale couldn’t; it therefore readily served as a perfect medium for the breakthrough of the nonmimetic image and its unique potential to express antagonisms—social, political, ontological—that were repressed in realism, for instance in the very bourgeois form of portraiture. Its revolutionary energy originated in the post-July Revolution reign of the “Bourgeois King,” Louis-Philippe, as soon as it became clear that he would not enforce the Charter granting freedoms and rights to the masses, but had “quickly adopted a policy of stasis as opposed to movement” (Vincent 13). Opposing this more middle-class force of status quo charged Philipon’s journal with new energy and determination, which found a particularly fraught battleground in the visual image, or as Vincent put it: “The power of this kind of opposition was unknown before the July Revolution because the censorship, abolished for the press, still remained for prints and lithographs” (18). Meanwhile, true to his popular name, the Roi Bourgeois made status quo his foremost goal in every matter of state despite persistent injustice and unrest, and his own expression, “juste milieu,” the happy medium or middle ground, came to typify his regime.

At the heart of the uncanniness of caricature and its overdetermination in nineteenth-century visual culture is its pervasive doubleness. Like “Les Poires,” the caricatures that appeared in Philipon’s magazine were frequently conceived by Philipon (though not usually sketched out) and drawn by more skillful artists like Daumier, Grandville, Traviés, and others. In a kind of micro sense, caricature staged a new form of collaboration between writer and visual artist. The relation between Philipon and Daumier in particular grew out of a mutual relation structured by the different media, where for instance, “[t]he Rabelaisian style of wit was more congenial and habitual to Philipon than to Daumier, all of whose independent satire—that is, work not in association with Philipon—had compassion and, in general, was unliterary and un-allusive to fiction” (27), as Vincent points out. And on the writer’s side “[i]t was fortunate for Philipon that he had an artist who could carry out his ideas with such skill, just as it was providential for Daumier that he had a director with such fertile ideas and such infectious enthusiasm” (43). This underscores the uniqu...