This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Counterculture flourished nationwide in the 1960s and 1970s, and while the hippies of Haight–Ashbury occupied the public eye, a faction of back to the landers were quietly creating their own haven off the beaten path in the Arkansas Ozarks. In Hipbillies, Jared Phillips combines oral histories and archival resources to weave the story of the Ozarks and its population of country beatniks into the national narrative, showing how the back to the landers engaged in "deep revolution" by sharing their ideas on rural development, small farm economy, and education with the locals—and how they became a fascinating part of a traditional region's coming to terms with the modern world in the process.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Ozarks Studies by Jared M. Phillips in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Historia & Historia del mundo. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

HistoriaSubtopic

Historia del mundoCHAPTER 1

The Making of a Hipbilly

We tried to change the world. And we got Nixon.

—“T”

THE TRADITIONAL PICTURE of a pioneer might include a covered wagon, perhaps a few children running alongside, crossing the grassy prairie of the American West. Those pioneers of yore were armed with a belief in Manifest Destiny and the hope of achieving self-sufficiency in a new, wild land. Pioneers in the 1960s and 1970s, however, eschewed the covered wagons for “Volkswagens, pickup trucks and sports cars.”1 The new settlers in the Ozarks were fortified not by Manifest Destiny but by an equally revolutionary philosophy, born of the ashes of protests and riots in places as far flung as San Francisco or Greenwich Village. They were, at least in the minds of native Ozarkers, “hippies,” and there were more “coming in every week,” with their “hair long and their hands soft.”2

These hipbillies were similar to Edwin Teale in that they knew little about the region. They differed in one important way, though. Where Teale saw the Ozarks as a quaint relic, the incoming hippies—though naive—saw in the Ozarks a place where they could “reduce the complexities of life to the traditional struggle of man against nature,” a response to the social revolutions that began throughout America during the 1960s.3 This generation of the BTL movement, lasting from roughly 1965 into the early 1980s, has been little addressed by scholars. This lack of detailed attention can be, in part, attributed to a benign disregard for this group of young revolutionaries’ intentions and wherewithal to homestead the rocky hills of the region.4

Just as the conversation about back to the landers nationally offers little beyond surface level discussions of the movement, the same is true in the Ozarks. Blevins’s discussion of the country hippies, in his masterful work Hill Folks, provides the most relevant conversation for our purposes. Blevins divides them into three groups: the general counterculture (described simply as “hippies”), urban escapists, and a disenchanted youth drawn to the area due to its promise of preserved traditional livelihoods.5 Definitions like this, also found in the works of Jacobs and Brown, provide those interested in the back to the land movement of the 1960s and 1970s with only a partial, external foundation for discussing the community that emerged in the Ozarks.6 As a result, there is little clarification given as to why people adopted this lifestyle, how they interacted with local communities, and how they lived out their lives in relation to the national counterculture.

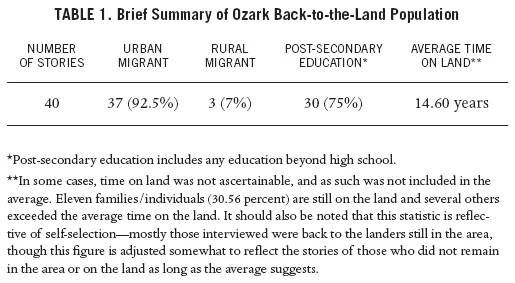

It is useful, then, to understand more fully who moved into the Arkansas hill country and went back to the land. (See table 1.) The stories compiled for this work were gathered via interviews conducted by the author and questionnaires returned to the author, and through newspaper archives, unpublished memoirs, and stories collected by members of the back to the land community. As such, the stories span the late-1960s through the early 1980s and cover experiences from the western, central, and eastern portions of the Arkansas Ozarks. From these sources, a picture of the group appeared relatively quickly, starting with their ages: nearly all of the BTLs moved to the region in their early- to mid-twenties, with a few who were younger and older.7 Reflecting the high rate of college attendance during the time, 75 percent had completed an undergraduate degree by the time they moved to the Ozarks, and 92 percent of the respondents came from urban areas such as Los Angeles or New York. Nearly all were white, from middle-class families, and had little practical knowledge of how to live “on the land.”

Hipbillies coming to the Ozarks were part of the same general population of young people that created more well-known places, like Black Bear Commune in northern California or The Farm in Tennessee. Indeed, this might be part of the problem in addressing the regional—and national—back to the land experiences. The common assumption that country hippies were bereft of ideological fortitude and a work ethic, built in part by the stereotypes portrayed in pop culture and the media at the time, was attached to groups such as those. Such an assumption, however, is belied by an in-depth examination of the group. Though some scholars, such as Dona Brown, have recently attempted to provide a corrective by noting that the movement was not isolated to the 1960s, her assertion that the BTLs should be associated “with the end of that era” or with “the beginning of the next” does not go far enough.8 By making such assumptions, Brown—like others writing about the back to the land community—unwittingly assumes that there was not a philosophy, a revolutionary intent, behind the back to the land movement in the 1960s and 1970s. Though commentators assumed a lackadaisical air presided throughout the BTL world, this is indeed far from the truth.9 The fact of the matter is that back to the landers from 1965 through the early 1980s were not only decidedly a unique addition to the tradition of self-sufficient agrarianism in America but were far more ideologically organized and successful than popular culture holds and previous scholarship argues.

Probing deeper into the motivations of the young neopioneers is admittedly difficult. Indeed, there are no simple reasons as to why people came to the Ozarks in particular.10 In order to understand and provide a broad framework of the push and pull factors that drew people to the Ozarks, we can briefly look at the story of two families for general trends in Arkansas’ BTL community, as well as the foundations of the deep revolution. In 1974 Bob Billig and his wife moved to the region from New York City, where he had been a teacher.11 After visiting places in Ohio and in the Appalachians, they finally settled in near Pettigrew in Madison County and were instrumental in founding the Headwaters School (a free school established by the BTL community in Madison County as a supplement to the rural education system and to provide community networking). The Billigs moved to the country, as Bob put it, in a wave of disillusionment and despair—it was “a mark of desperation that we left anyhow.”12 This feeling of angst pushed Billig and his wife to try and “find an alternative narrative for our lives, preferably closer to the earth.”13 In part, their search was for a connected, rooted home and community in a world that seemed to have lost these things. Upon their arrival, Bob and his wife found exactly this. A few weeks after they arrived in Huntsville they

journeyed south to Pettigrew to meet [the contact person] that brought us here and were immediately invited to go to a local swimming hole. We piled into the open back of his pickup truck and bounced down miles of dirt road . . . We were greeted by a scene that changed our lives: 30–40 naked hippies, with children, playing in the water and socializing on the river banks. We said to each other, “We’ve found a home.”14

Others, like Joel and Sherri Davidson, who also lived in Madison County near Pettigrew, expanded on this idea. (Indeed, the Davidsons were part of the initial conversations surrounding the Headwaters School and the Upper Friley Organization.) The Davidsons brought a distinctly utopian tone with them as they set up shop outside of Pettigrew. The Davidsons, like the Billigs, moved in part to get away from prevailing society and from a government Joel saw as repressive, with the hope of unplugging from the mainstream of an increasingly consumptive culture.15 Citing Henry David Thoreau as a key influence, Joel wanted to live a more deliberate life and no longer be mired in “quiet desperation.”16 Davidson wanted to focus not on living “cheaply” or “dearly” but rather on an existence that allowed him to “transact some private business with the fewest obstacles,” that is, to practice revolution.17 Indeed, by joining the back to the land movement, Davidson saw himself not as part of an alternative culture, but as exiting a “dominant culture” that was simply a “thin veneer of civilization,” and a rapidly failing one at that.18 For Davidson, like many, creating a localized utopia in the Ozarks seemed to be the answer to society’s ills.19

While not all the individuals or families who moved from the cities to the hills consciously possessed a vehement philosophical or revolutionary bent, when examined as a group it becomes readily apparent that instead of a movement bereft of goals or purpose beyond fleeing the 1960s, back to the landers at large and in the Ozarks in particular held a deceptively simple vision paired with attainable goals. The back to the land community possessed a belief in a deep revolution that maintained the dreams of the political fights of the 1960s but linked those dreams with the emerging deep ecological consciousness of writers like Gary Snyder or Wendell Berry. As a result, the group believed the world could be remade. Instead of street protests and violence, the deep revolution could only be achieved via a sociocultural reset rooted in a reconnection with the natural world. While utopian, this vision readily afforded measures of success at the individual and community levels.

The back to the land movement, then, was an effort to rebuild society, as BTL member Crescent Dragonwagon told Ruth Weinstein, a fellow hipbilly who conducted a series of interviews throughout the community in the early 1990s. In 1970 Dragonwagon and her partner moved to the Ozarks, where she hoped they might “build a new society from the ashes of the old, building a collective, cooperative society instead of one founded on Social Darwinism.”20 Dropping out of American life at large was part of how this would happen. Others interviewed by Weinstein voiced the same view. “B,” an anonymous voice, put it this way:

The solution to the problem with the government—as perceived by the back-to-the-landers—was to withdraw and form, alternative cultures, alternative economies . . . In one sense you could be an isolationist/activist, in that you are actually doing the kinds of change that you advocate for others . . . But anyway what we were doing at that time was trying to demonstrate that attitude, to accept a more cooperative way of living, to realize that we could do with less, be happy with less.”21

The sentiment was repeated throughout the rest of Weinstein’s interviews and matches with the interviews recorded for this study as well. “J” and “T” agreed with the impulse to drop out and intentionally isolate themselves but noted that there was also an impulse for changing society at large.22 “J” argued that while the BTL community lived isolated existences to a degree, they were not completely “disconnected from society. I think a lot of people’s initial thing was to totally drop out. I think in the long run that everybody wanted to make some kind of change at the same time.”23 This impulse for a different kind of change was readily understood as a result of the 1960s chaos. “N,” reflecting both on the aftermath of the stunted revolutions of previous years and the prevailing mood of the 1970s, argued, “We were looking for social change, to create that society, because we weren’t happy with the one that was out there.”24 What was out there? “We came out of the sixties where we fought politically. We went to demonstrations. We tried to change the world. And we got Nixon. I mean I think that’s why we left and why other people our age left.”25 As they left the cities, the drive to institute social change did not diminish, rather it evolved into a sophisticated ecological consciousness befitting the grand American intellectual traditions represented by Thoreau and others. Central to the urge to move back to the countryside was the neopioneers’ overarching desire to not simply remove themselves from the main of American life but to begin building a new world, at least at the individual and community levels. Key to this was a rejection of the consumption-driven lifestyle dominating the United States at the end of the 1960s.26

As David Shi has aptly shown, in the wake of World War II, American consumers and marketers and manufacturers developed a relationship wherein the producers demanded Americans buy more and more to believe that not only was infinite economic growth possible but “essential,” and that hedonism based on consumption should be the name of the game—and the American public was happy to comply.27 The counterculture as a whole, and the BTLs specifically, had a different understanding of how the world operated. While not rejecting everything the system had built—food stamps and welfare were often a part of the early days of the back to the land experience—country hippies advocated a way of life that was a far-reaching shift from mindless materialism, reviving “a radical transcendentalism that called for revolutionary change in consciousness.”28 So while political protests and radical demonstrations were without moral suasion by 1968 and 1969, hipbillies felt that “to restore meaning in America required a revolutionary change in the individual perception, a dramatic transformation in the way people viewed themselves and the world.”29

Though young and jaded, these advocates of deep revolution did not wander completely blind into the wilderness with axes and acid. America has had a longstanding affair with notions of self-sufficiency. Rarely, however, do they succeed in breaking into the national consciousness with the lasting power on popular culture that the neopioneers had. As the events of the early 1970s once again placed these ideas at the forefront, figures like Aldo Leopold, Helen and Scott Nearing, and others became patron saints to a generation that eschewed organized religions for Eastern-flavored mysticism aided by generous doses of weed, acid, and booze.30 While the country hippies may have lacked a thorough historical context for their movement, they were often familiar with at least one or two of these figures. Combined with longstanding counterculture prophets such as Gary Snyder and relatively new sages like Wendell Berry, these voices served as guides for the nascent communes, couples, and individuals in their quest to live a life of simplicity joined with the mysteries of the natural world.31 Indeed, it may be that only by delving into the intellectual and mystical life of the country hippies can the appeal of the back to the land moment be fully understood.

While Thoreau had set the model, as it were, for critiquing urban life, by the 1920s his ideas seemed to need refinement. This update came through Ralph Borsodi’s writings, which served as a major influence on the trajectory of modern back to the landers.32 Borsodi, founder of the School of Living and one of the central agrarian theorists of the twentieth century, came of age as a writer in New York just before and during the Great Depression. His writing was strongly influenced by his father’s work with Bolton Hall on the iconic A Little Land and a Living, a book that “played an important part in the back to the land movement that took place during the banking panic of 1907.”33 Throughout his life Borsodi “aimed at creating a systematic economic theory of decentralization, one including a compelling integration of hom...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Foreword | Crescent Dragonwagon

- Acknowledgments

- Preface

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 | The Making of a Hipbilly

- Chapter 2 | Pioneers in an Age of Plenty

- Chapter 3 | Hipbillies and Hillbillies

- Chapter 4 | Hipbillies and the New Ozarks

- Chapter 5 | The Ozark Mystic Vision

- Chapter 6 | Hipbillies Triumphant

- Conclusion | The Affection for Place

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index