![]()

1

Before Little Rock

1894–1926

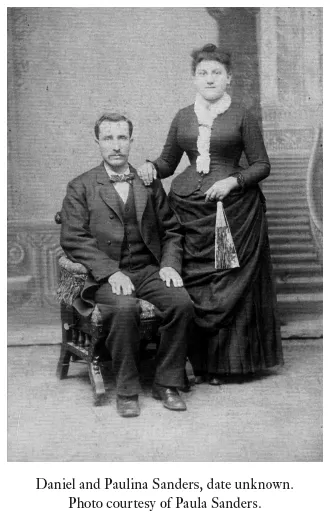

A BRIEF LOOK AT Sanders’ early life provides insight into his motivations and later activities. He was born on May 6, 1894, to immigrant parents Daniel Sanders and Paulina Ackerman Sanders in Rich Hill, Missouri, seventy-five miles south of Kansas City, near the Kansas border. Founded in 1880, Rich Hill was a small farming and coal mining town of fewer than two thousand that Daniel Sanders jokingly referred to as “Poor Prairie,” as there were no rich hills to be found.1 Daniel had been born in Soetern in the Kingdom of Prussia. Daniel’s father—Ira’s grandfather, whom Ira called “Grandpa Sender”—was a deeply religious man, known by the villagers in Soetern as “Fromsher Sender,” the most devout man in the village, from the Yiddish word frum, meaning pious. The family name, “Alexander,” was over time shortened to “Xander,” then changed by Ira’s grandfather to “Sender,” and finally anglicized by Daniel to “Sanders” following his immigration to the United States.

After he and his family immigrated, Daniel Sanders became a naturalized US citizen in January 1871 in Linn County, Kansas, just west of Rich Hill. He worked in Fort Scott, Kansas, as a butcher and wholesale meat packer, barely making ends meet. Daniel met Paulina Ackerman sometime after the death in 1880 of his first wife, Hannah Lederman Sanders, with whom he had a daughter, Jessie.2 He and Paulina—whom everyone called “Lina”—married on August 13, 1883, in St. Louis, and the couple would have four children together: sons Morris, Ralph, Ira, and Gus. In 1900 the family relocated from Rich Hill to the growing frontier city of Kansas City, Missouri, where six-year-old Ira began public school. Ira’s mother worried about the worldly influences upon her children in this diverse and growing metropolitan environment. In particular, she warned Ira and the other children to “never go near” two “wicked women” who lived at the end of their block because “they use rouge!”3 Paulina instilled in young Ira a strong sense of morality, religiosity, and propriety that he would carry with him throughout his life.

Born to the Rabbinate

Even in childhood I expected to become a rabbi.

—IRA SANDERS, 1954

Young Ira Sanders knew by the age of nine that he would become a rabbi, a feeling influenced both by a desire to help others and by his deeply religious mother Paulina, who took her two youngest sons Gus and Ira to Sabbath services every Saturday morning, and whose “one aim in life was to have one of her four sons enter the rabbinate.”4 As a child, Ira often pretended to be a rabbi, going so far as to lock himself and his younger brother Gus in their bedroom together in order to force his brother to listen to his sermons.5 In Kansas City, Paulina tried to facilitate her son’s desire to be a rabbi by arranging Hebrew lessons for him with a local Orthodox rabbi. This rabbi, though, apparently dissatisfied with his career and increasingly an object of criticism in the local Jewish community, scoffed at Ira’s ambitions, pointedly asking his mother, “Why do you encourage him to become a rabbi? Rather let him be a shoemaker.” An outraged Paulina then related this story to their rabbi, Dr. Harry Mayer, who said, “You go back and tell that rabbi that he should be a shoemaker. Ira will be a rabbi.”6

Rabbi Harry Mayer had come to Kansas City and Congregation B’nai Jehudah from Arkansas following a two-year stint (1897–99) as rabbi of Little Rock’s Congregation B’nai Israel. This Little Rock–Kansas City connection would prove very important in Sanders’ later life. Mayer arranged for Ira to have Hebrew lessons, and he told young Ira that once he had “progressed sufficiently in Hebrew,” he would personally mentor him in preparation for eventual admission to Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati.7 In Dr. Mayer, young Ira had found a mentor and role model to guide him on his path to the rabbinate.

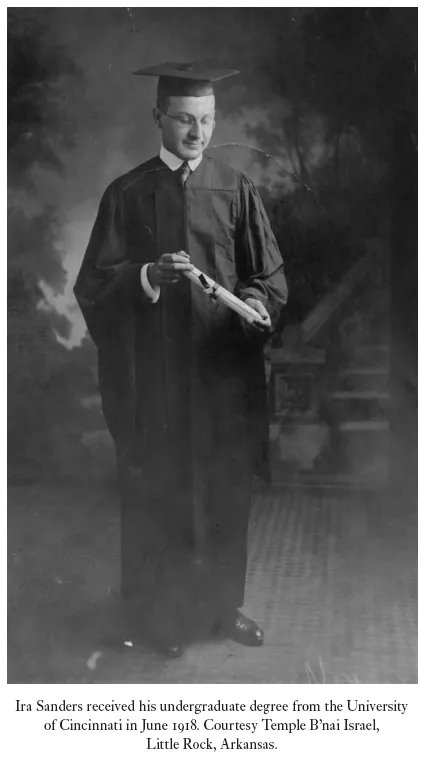

Sanders pursued his dream of the rabbinate throughout his years in the Kansas City public schools and later in Cincinnati, where the seventeen-year-old Sanders arrived on September 1, 1911, to begin his studies at Hebrew Union College (HUC), the primary training ground for Reform rabbis in the United States. He recalled that, like himself, “most students entered the Primary Department of the seminary while yet high school undergraduates and [later] attended the Collegiate Department” through the University of Cincinnati, undertaking a broad range of courses in the liberal arts that culminated in a final period of intensive rabbinical studies. While in Cincinnati, Sanders lived in a boarding house on a budget of thirty dollars per month, most of which had been borrowed from the HUC student loan fund. Of this, twenty-five dollars went to room and board (including a daily boxed lunch prepared by “Mrs. B,” the stern wife of the boarding house proprietor), leaving him a five-dollar-per-month spending allowance.8

Sanders would relate the story of the time Mrs. B, whom he recalled as being possessed of “a rather ungovernable temper,” unilaterally and unexpectedly raised the rent. In the spring, as Passover drew near, she announced an increase in the room and board to thirty dollars per month to cover, she said, the increased cost of special Passover food. Such an increase would consume Sanders’ entire monthly budget. He considered the surprise increase unfair and said he would refuse to pay it; as a result, on the morning of the first day of Passover, an angry Mrs. B forcibly threw him out of the house, threating to shoot him if he returned—a very real threat considering the active rumor among the boarding house boys that Mrs. B had once, as a result of a family quarrel, threatened to shoot her own sister. Sanders communicated his ouster to his friend and classmate Julius Liebert, a young seminarian of considerable stature and strength, who accompanied Sanders back to the boarding house where Mrs. B’s husband, small of stature, awaited with his hand raised to strike young Ira should he approach the door. The beefy Liebert interposed himself and said “if you as much touch a hair on that boy’s head, I’ll give you a whipping the like of which you have never had.” Sufficiently intimidated, the landlord thought better of his planned course of action, and all parties agreed that Sanders would remain at the boarding house at the agreed-to rate of twenty-five dollars a month. Mrs. B never again broached the topic of rent increases.9

Sanders and his four housemates occasionally played practical jokes on the disagreeable Mrs. B. The boarding house was notorious for its skimpy mealtime portions, leading fellow resident Harvey Franklin to compose a ditty the boys sometimes would mockingly sing at meals, to Mrs. B’s great consternation: “Glorious! Glorious! One cup of milk for the four of us!” The boys once concocted a scheme to increase their meager meal portions. They passed off a fellow student as the visiting learned scholar “Dr. Goop” of Berlin, and Sanders and the other boarding house boys told Mrs. B they would like to have this important guest over for Sunday dinner. She fell for the ruse, saying she felt honored to have such a visitor, and prepared a sumptuous spread for that evening’s dinner; “for once,” Sanders later wrote, each person “was fully sated,” with Mrs. B never the wiser.10

Sanders received rabbinic ordination from Hebrew Union College in April 1919, as the city and the campus bustled with the return of GIs from the First World War. Sanders cited HUC president Kaufmann Kohler, “foremost theologian of his day,” among other instructors, as great influences on his later life, recalling their emphasis on the traditions of prophetic Judaism.11 Sanders later wrote that the primary realization he took from his years at Hebrew Union College was “Judaism’s role in the moral drama of mankind.” The Jew, wrote Sanders, has always “been under a burden of responsibility.” This burden “gladly becomes a joy for him once he understands the place he fulfills in the economy of life on earth.” The Jew must pursue the ideal “not of mastery, but of service” to mankind. If he does not understand this, “that he is the vehicle of a sublime purpose, if he weakly and foolishly expects that he can enjoy the privilege of being himself without service, better he quit than to be faithless to his divine election.” Judaism has “given to the world the concept of service,” a calling to a higher purpose. This call to service would be the governing concept of Ira Sanders’ life in the rabbinate.12

Allentown

Those years in Allentown were most rewarding.

—IRA SANDERS, 1978

After ordination, the twenty-five-year-old Sanders fielded a number of pulpit offers for his first rabbinate from congregations across the country. Temple Beth Israel of Tacoma, Washington, and Temple Israel of Tulsa, Oklahoma, both actively recruited Sanders in 1919, as did Congregation Keneseth Israel of Allentown, sixty-one miles northwest of Philadelphia in eastern Pennsylvania.13 The young rabbi accepted the Allentown offer and gave his first sermon on Friday, September 12, 1919. Fluent in German, the language of his father and grandfather, Sanders was at home in Pennsilfaanisch Deitsch, the Pennsylvania Dutch of the area. This language and culture thrived in the region as a result of substantial German immigration to the area from the seventeenth to the late eighteenth century. Sanders realized his knowledge of conversational German would serve him well in his new pulpit when, on his first day in Allentown, the rabbi went to a cafeteria for lunch and, making his way down the line, asked the server for potatoes. “Ach die grundbeere sind all,” came her high-pitched reply in Low German (Plattdeutsch) slang, which Sanders understood: “The potatoes are all gone.” His facility with Low German gave him greater access to his congregation and community, as it allowed him to minister to congregants with very limited or no English skills. On one such occasion, Sanders visited a sick congregant who lived “on the third floor of an old dilapidated flat” and spoke almost no English. Sanders paused as he reached for the doorbell, knowing he had arrived at the right place when he saw a sign on the door scrawled in broken English: “Bell don’t button. Bump.”14 His language skills helped make him a very popular rabbi in Allentown.

While in Allentown, Rabbi Sanders founded the Jewish Community Center after working hard within the community to organize and to solicit donations to build it. “The necessity of immediate funds is the only obstacle in our path at present,” he wrote in 1920.15 He and the local Jewish community dedicated the new community center later that year, and within it Sanders founded a Talmud Torah, a religious school “that gave instruction in Bible, liturgy, and simple Talmudic passages” with a faculty of five and himself as principal. “In those days,” Sanders said, “the Center seemed to be the focal point around which all activities dealing with the Jew and Judaism revolved, so that I early learned a great deal about the so-called Center movement.” He directed the religious school and the community center for four years. In addition to his duties as rabbi and community center director, Sanders taught primarily Orthodox children in an Allentown Jewish day school. He asked one of his Orthodox rabbinic colleagues “why they had chosen me, a Reformed rabbi, a rabbi with a liberal tendency towards everything,” to teach in their day school. He was gratified at the response: “that I had a great deal of empathy for all people, in particular those in my own faith who differed from me philosophically, theologically, and otherwise.” Rabbi Sanders did not neglect his own education while in Allentown. It was his habit to rise early each morning to study before breakfast, and while in Allentown he travelled weekly by train to New York City and Columbia University, leaving at two o’clock in the morning to attend classes part-time “and meet with my early morning professors.” Sanders would earn his Master of Arts degree in sociology in 1926, and he began, but never completed, work towards a doctorate in sociology. He studied with and was influenced deeply by such luminaries as philosopher John Dewey, anthropologist Franz Boas, and sociologist Frank Giddings. Boas was a particular influence upon Sanders’ notions of race and racism. “Boas and his students,” writes historian Lynn Dumenil, “led the way in challenging hierarchical assumptions about race,” finding no scientific basis for them, and refuting as deeply flawed such devices as IQ tests then used to assert African American biological inferiority.16

Sanders participated in and supported a variety of Jewish philanthropic causes while in Allentown, and in the process he rubbed shoulders with a few powerful figures of the era. The groups in which Sanders played an active role included the Eastern Pennsylvania Joint Distribution Committee, an arm of the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, established in 1914 to “facilitate and centralize the collection and distribution of funds by American Jews for Jews abroad.”17 Sanders became involved in this charitable endeavor at the invitation of two prominent businessman: Max Hess, cofounder of the Hess Brothers chain of department stores and a member of his Allentown congregation (Hess “attended regularly each Sabbath evening service” and “always sat on the last row,” Sanders recalled, so as not to call too much attention to himself), and Jacob Schiff, a New York financier and one of the most prominent and generous philanthropists of his era. Schiff’s firm—Kuhn, Loeb, and Company—played a key role in the financing and development of such iconic American industries as Westinghouse and AT&T, and Schiff himself generously gave to dozens of charitable causes such as New York’s Montefiore Hospital and the American Red Cross. Schiff also supported through substantial contributions such institutions as the Henry Street Settlement House, Barnard College (to whom he donated $1 million), and the Tuskegee Institute.18 Shortly before his death, Schiff invited Hess and Sanders to a meeting in his New York City office to discuss plans for their 1919–20 campaign in Eastern Pennsylvania. Sanders deemed the work of the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee particularly important at that time, given “the chaotic period which followed World War I” in Europe.19 He played an important role as organizer, fund raiser, and promoter of the Joint Distribution Committee’s activities in Pennsylvania throughout his Allentown tenure.

Always dedicated to the furtherance of Jewish education, Sanders travelled extensively while based in Allentown as president of the Pennsylvania Federation of Religious School Teachers, which “brought together in annual sessions the educators of most of the Reform Jewish religious schools of Eastern Pennsylvania.” Throughout his tenure at Congregation Keneseth Israel, he spoke often throughout the region before different groups regarding Jewish education and maintained an enthusiastic association with the Jewish Chautauqua Society of Philadelphia, whose executive secretary Jeanette Goldberg often assisted him with his work both as a rabbi and an educator.20

While in Allentown, Sanders played a prominent role in Keren haYesod, the Palestine Foundation Fund, established in 1920 to assist Jews in relocating to Palestine. He “travelled extensively throughout Pennsylvania conducting campaigns, giving lectures and in general,” he later wrote, “encouraging and promoting Jewish life in Palestine.” At this point in his life, however, Sanders was neither a Zionist nor an advocate of the creation of a Jewish state. He was not a Jewish nationalist. In Sanders’ words, “the express purpose” of Keren haYesod was “to solicit money to be utilized in promoting the religious, cultural, and economic welfare of the Jewish settlers and inhabitants of Palestine.” Absent from Sanders’ description is any mention of the creation of a Jewish state. Zionism was not a tenet of Reform Judaism. Sanders advocated and supported Jewish life in Palestine insofar as it was the right of Jews to live unfettered alongside those of other faiths in the Holy Land. Following World War II and the horrors of the Holocaust, ...