Part 1

Answering the Critics

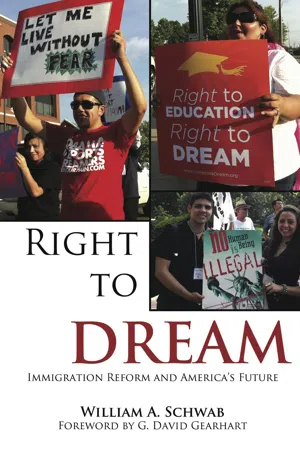

As with other domestic issues, Americans are deeply divided in their beliefs about the long-term effect of our current immigration policy. Some groups, like the Cato Institute, see immigration as a key to a robust and expanding economy, a continuation of the melting pot process that has made America great. Other groups, like the Federation for American Immigration Reform (FAIR), see the rapid increase in racial and ethnic minorities as a threat to America’s European heritage. As a result immigration has become this decade’s hot-button political issue, not only because of the dramatic increase in the number of immigrants in the past thirty years but also because immigration is the process that defines who we are as a people.

Some Americans feel threatened by these changes. Parties attracted to the immigration debate sometimes respond emotionally when they sense jobs, health care, education, and national security are at risk. In such a charged climate, it is not surprising that Congress has been unable to address comprehensive immigration reform, and the DREAM Act has been at the center of this debate. With no consensus at the national level, states have moved to fill the political vacuum, but state governments are moving in two different directions. On the one hand, fourteen states have decided to improve the opportunities for undocumented students in higher education with the passage of the DREAM Act.2 On the other, states like Arizona, Alabama, and Florida have passed laws limiting access to higher education for undocumented students, arguing that they are protecting taxpayers.

Landmark social legislation occurs at the confluence of economic, social, and political forces. Historians usually write about the leaders who framed laws and, through the power of their personalities, passed them. In reality, passing landmark legislation requires a Congress who represents an electorate whose attitudes are shaped by the state of the economy and the society and a collective willingness to accept social change. History is replete with examples. President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the Social Security Act on August 14, 1935. Although controversial, the legislation passed the House 372 to 33, with 81 Republicans voting in support, and the Senate 77 to 6, with 16 Republicans supporting. Thirty years later, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Medicare bill into law on July 30, 1965, after passing the House 307 to 116, with 70 Republicans supporting, and the Senate 70 to 24, with 13 Republicans voting for the bill. The same pattern persisted with the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Were they controversial? Yes. Were they products of their times? Yes. Can the vast majority of Americans conceive of a society without Social Security and Medicare? Probably not. Most appreciate the role these laws have played in creating a civil society. But ask yourself, “Would any of these bills pass Congress today? Would there be an attempt to cross the aisle, compromise, and vote for what was good for the nation? Would the majority of Congress cast a vote for the common good?”

The 2012 presidential election was a game-changer. Congressional Republicans have stalled immigration reform and the DREAM Act for a decade, but the growing share of Hispanic voters, which helped reelect the president, is likely to double by 2030. Heeding the warning, prominent Republicans are launching a new super-PAC, Republicans for Immigration Reform, with the hope of repairing the political damage left by years of anti-immigrant rhetoric. Political relevance, not the common good, is driving these efforts, but it is creating the best chance for comprehensive immigration reform in a generation. But words are cheap, and the American people should not be surprised if Congress cannot pass a comprehensive immigration reform bill. This is why the states must continue to provide leadership on this issue.

In the next five chapters, I explore the key issues surrounding passage of the DREAM Act. What are the issues that divide? What do the proponents and opponents of the DREAM Act argue? Is there a middle ground? Is compromise possible? As with all controversial legislation, arguments on both sides abound. I believe the following five arguments are the ones most commonly and most forcefully set forth by opponents of the DREAM Act:

Legal. Undocumented students are criminals. They are breaking the law. Passing the DREAM Act would reward criminals by extending higher education to undocumented students. The criminals should go home, get in line, and apply to enter the country legally.

Immigration. Passing the DREAM Act would lure more illegal immigrants to the United States. More families would attempt illegal entry so that their children could receive an education and attain legal status. The DREAM Act would cause an increase in illegal immigration.

Economic. Undocumented residents are a tax burden. They consume services and do not pay their way. They exacerbate state budget shortfalls in a time of recession. Trapped in low-paying “immigrant jobs,” they contribute little to the economy and less to the tax base.

Culture. They are changing our national character. We are a white, Christian nation grounded in a European heritage.

Assimilation. Undocumented immigrants will not be a part of the melting pot, because they live in insular, non-English-speaking communities bound by networks of kin and friends.

One

These Children Are Blameless

Legal. Undocumented students are criminals. They are breaking the law. Passing the DREAM Act would reward criminals by extending higher education to undocumented students. The criminals should go home, get in line, and apply to enter the country legally.

The critics of the DREAM Act argue that Congress twice clearly stated the nation’s position on illegal immigration during the Clinton administration by passing the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996 (PRWORA) and the Illegal Immigrant Reform and Immigration Responsibility Act (IIRIRA). These laws addressed several immigration concerns of that time: removing incentives for illegal immigration, limiting benefits to those who were here illegally, and barring illegal immigrants’ employment in highly skilled jobs.1

The critics also note that in their 1982 ruling in Plyler v. Doe, the Supreme Court distinguished undocumented children from adults who illegally came to the United States, and their ruling required states to provide K–12 education to undocumented children. In IIRIRA, Congress codified the distinction between children and their parents, and because the court did not extend educational benefits beyond primary and secondary education, once children reached eighteen the law required them to correct their undocumented status. In other rulings the court recognized that illegal residents in the United States enjoyed protection of their fundamental rights under the Constitution, but opponents note the court did not classify education as a fundamental right.

The critics also argue that the DREAM Act would negatively impact the nation’s immigration policy. First, they claim that the act would discourage young adults who have reached the age of eighteen from correcting their illegal status. Second, state DREAM Acts would circumvent Congress’s ability to control the immigration and naturalization process. And third, giving undocumented students in-state tuition benefits would reward illegal behavior and give undocumented students preferential treatment. Moreover, they note, IIRIRA does not bar undocumented students from higher education; rather, it requires them to pay out-of-state tuition.2

First, I will put the DREAM Act in a legal context. In 1982 the Supreme Court held in Plyler v. Doe that Texas violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment by denying undocumented school-age children a free public education. Justice William J. Brennan wrote for the majority, and his words are as relevant today as they were thirty years ago.3

Justice Brennan notes that because of lax enforcement and our unwillingness to bar the employment of the undocumented, our society had created a “shadow population” of illegal immigrants, numbering in the millions. Little has changed in three decades—today, the nation has 11.2 million undocumented residents, including 2.1 million children and young adults.

Justice Brennan continues, “The existence of such an underclass presents most difficult problems for a Nation that prides itself on adherence to principles of equality under law.” He notes that adults who enter our territory illegally should be “prepared to bear the consequences, including, but not limited to, deportation.” But he makes an important distinction in that “the children of those illegal entrants are not comparably situated.” Simply, children are not responsible for the behavior of their parents; they represent a special case.

Justice Brennan then describes the special role of education in our society as follows: “In addition to the pivotal role of education in sustaining our political and cultural heritage, denial of education to some isolated group of children poses an affront to one of the goals of the Equal Protection Clause: the abolition of governmental barriers presenting unreasonable obstacles to advancement on the basis of individual merit.” So this right of individual advancement is protected by our Constitution, and it remains, after more than two hundred years, a core American value. We are a meritocracy.

Justice Brennan concludes:

Paradoxically, by depriving the children of any disfavored group of an education, we foreclose the means by which that group might raise the level of esteem in which it is held by the majority. . . . The inability to read and write will handicap the individual deprived of a basic education each and every day of his life. The inestimable toll of that deprivation on the social, economic, intellectual, and psychological wellbeing of the individual, and the obstacle it poses to individual achievement, make it most difficult to reconcile the cost or the principle of a status-based denial of basic education with the framework of equality embodied in the Equal Protection Clause.

Justice Brennan reasons that without the basic skills education provides, these undocumented children would become part of a permanent underclass. Consequently, the court ruled that undocumented children were entitled to the same K–12 education that the state provided children whose parents were citizens. But the law did not extend this guarantee to postsecondary education.

I believe the principles identified in Plyler v. Doe are as relevant today as when they were written. Education is indispensable to our society. It is the foundation of our democracy. It contributes to the common good. It is necessary for meaningful participation in our economy and society, and it is the major contributor to upward social mobility. It is doubtful that any child could succeed in our society if denied the opportunity of an education.

But much has changed in our society and economy in the past thirty years. We are no longer an industrial society but a postindustrial one. We still make things, but products from our knowledge- and information-based economy have eclipsed those from manufacturing. When students graduated from high school or college thirty years ago, they competed with graduates from their communities, states, and region. Today, with the mixed blessings of the Internet, graduates compete with millions of others worldwide. In the recent past a high school education and a union job helped to ensure a middle-class lifestyle. With the collapse of unions and the rise of a global economy, a high school education alone would keep someone at the margins of our society. So a K–12 education was to the twentieth century what a K–16 education is to the twenty-first.

Our Constitution and laws are living documents, and as our society has changed our Congress, our states’ legislatures, and our courts have created a legal system that has served the needs of each generation of Americans. Our nation must now recognize that we are amid the fourth great wave of immigration in our history, and, as in the past, this wave will reinvigorate and change us. In Plyler v. Doe, Justice Brennan recognizes the necessity to educate undocumented children in order to help prevent their exile to the permanent underclass, and it is vital that our generation recognizes that 2.1 million young people require more than a K–12 education. They need a higher education in order to avoid the exile Brennan argues against.

The critics of the DREAM Act argue that it would discourage young adults who have reached the age of eighteen from correcting their illegal status and claim that without the act an undocumented youth, in order to gain legal status, need only return to her or his native country, apply for legal admission to the United States, and get in line for a visa. Framing the argument differently, these critics want us to educate undocumented children; to allow them to make friends, attend public schools, participate in their communities, and become Americans, except for their immigration status; and then, when they turn eighteen, to deport them. Are these young people any more culpable for their parents’ actions after they reach the age of majority at eighteen? A growing number of Americans think not.

I have conducted interviews and focus groups with undocumented students, ESL teachers, school administrators, and governmental officials; I have attended regional and state DREAM Act conferences; and I have learned that the go-home-and-get-in-line position ignores reality. First, is it a reasonable alternative? Would an undocumented youth who returned be able to get a visa in, say, a year or two? The answer is no. The U.S. immigration process is chaotic, time-consuming, and expensive. At the end of 2010, 1,381,896 Mexicans (the source of 60 percent of our immigration) were still waiting for their green card applications to be accepted or rejected. The United States currently makes only 5,000 green cards annually available worldwide for low-wage workers to immigrate permanently; in recent years only a few of those have gone to Mexicans.4 The reality is that an undocumented youth could not leave, return legally, and restart life in the United States. The majority of young adults that I interviewed knew this and lived in constant fear of being stopped, arrested, detained, and deported. When I talked to them, they said that the fear was always just below the surface, and the fear was palpable in my interviews, usually accompanied by tears. In one of my focus groups with undocumented students, one-third were being treated for depression because of this underlying fear.

How could it be otherwise? These young people have been raised, educated, and socialized as Americans. English is their first language, and their hopes, values, and beliefs are American. When I explored their lifestyles, I found that what they wore, listened to, and admired came from American popular culture. They share our language and culture, and yes, they have rich networks of family, friends, and neighbors. But those networks are here.

Critics argue, however, that these young adults would be fine if they were to go back to their native countries—that they would have kin, friends, and neighbors to support them. In my research I found the opposite to be true. Most of these young people came to the United States at a very young age and have little or no memory of the family and neighbors in their native country. With increased border security, return trips for visits and holidays are impossible. Their parents keep relationships alive through international phone calls, but these are not ties that bind a younger generation. Therefore, most of these young people, if deported, would be strangers in a strange land.

Another wrinkle in the opponents’ argument is little known or appreciated. About one-third of the students I interviewed were from mixed-status families. For example, Carlos, whom I interviewed at a District 8 United We Dream conference, was brought by his parents to the United States for medical treatment when he was two months old.5 He would have died in Mexico, but the hospital stay in Kansas City saved his life. His parents overstayed their visa, joined Kansas City’s Latino community, and worked in the underground economy to support their family.

Today, his parents have permanent residency, and his younger siblings are citizens because they were born here. Carlos is the only undocumented member of his family. He has never met his Mexican kin, has talked to them only a few times, and became visibly upset when the subject of deportation was brought up. Carlos told me:

I’m an American. There were only two other Latinos in my high school. I know where I came from, uh, I know I’m Latino. . . . I just think of myself as . . . like I belong here . . . this is my country . . . right? Do you understand me? I played football and basketball in high school. I’m a good student. High school was incredible. The teachers and kids were great to me. I really did well. I really belonged. Great years. It was great. The guys I played sports with and my girlfriend Allison, you know, Allison and her friends, wer...