![]()

CHAPTER 1

Into the Factories

When men left to serve in the armed forces during World War II, their absence created a labor shortage throughout the United States. By 1943, government officials and industry leaders looked to women workers to contribute to the production needs created by war. Nearly six million American women took jobs that they had not traditionally held before: in factories and plants and on farms. Work in wartime production allowed women to express patriotism and gain financial independence. In these positions, women helped to sustain the booming industrial and agricultural sectors—a crucial factor in helping the Allies win the war. The documents in this section show how the presence of women in industry challenged traditional views of women’s work. Though most lost their jobs when soldiers returned from war, women proved in a very visible way that their capabilities extended beyond traditional roles as wives and mothers. After the war, women were expected to give up their jobs in factories to the returning soldiers and resume their roles as wives and mothers. Although in reality many working-class women continued to work in wage labor, an ideal of domestic life re-emerged that cast men as the breadwinners and women as the bread makers. The model postwar family was popularized in television sitcoms such as Leave It to Beaver and The Donna Reed Show. Though women continued to pursue new opportunities outside of the home, it was not until the late 1960s that society began to publicly revisit and question the importance of women’s rights.

DOCUMENT 1

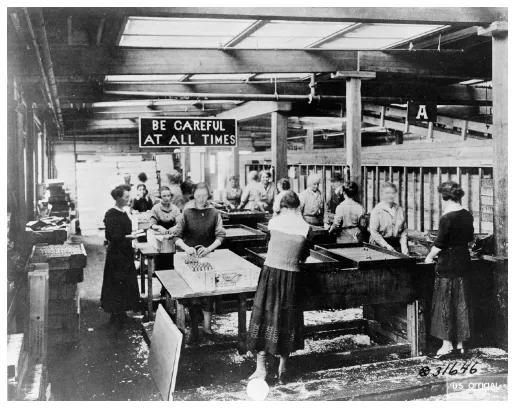

Photograph, Women Assembling Hand Grenades, ca. 1918, from the Army Industrial Service Section, Women’s Branch, US War Department

Courtesy of the Library of Congress, LC-USZ62-116444.

Though women joined the industrial workforce in unprecedented numbers during World War II, smaller numbers held manufacturing jobs during World War I. This image shows women immersing bouchon assemblies (or enclosures) for hand grenades in Vatudrip (a liquid to prevent rust) at Gorham Manufacturing Company in Providence, Rhode Island. Gorham was a major metals manufacturer that supported the war effort during World War I. Few female industrial workers remained on the job after hostilities ended in 1918.

DOCUMENT 2

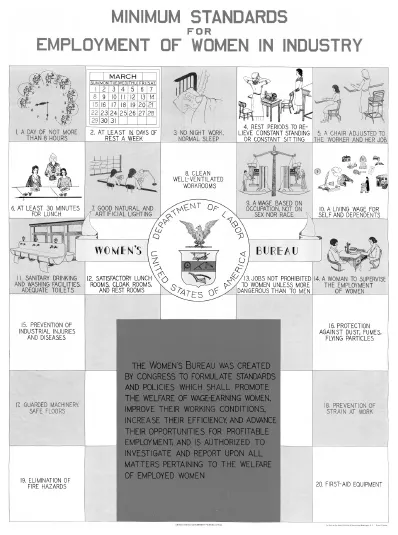

Poster, US Department of Labor, “Minimum Standards for Employment of Women in Industry,” 1940

Courtesy of the US Department of Labor.

The US Department of Labor’s Women’s Bureau created this poster before the bombing of Pearl Harbor and the United States’ entry into the war. The poster lists twenty standards that were intended to “promote the welfare of wage-earning women.”

DOCUMENT 3

Franklin D. Roosevelt, “Executive Order 8802—Reaffirming Policy of Full Participation in the Defense Program by All Persons, Regardless of Race, Creed, Color, or National Origin, and Directing Certain Action in Furtherance of Said Policy,” June 25, 1941

As the United States began to prepare for war, millions of jobs were created in defense industries. Yet African American workers were largely excluded from industrial work. A. Philip Randolph, president of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, and other leaders began the March on Washington Movement in 1941 in an effort to eliminate discrimination in the war industries and the armed services. Randolph threatened to bring “ten, twenty, fifty thousand Negroes on the White House lawn” if their demands were ignored. The threat of a march on the nation’s capital led President Roosevelt to issue Executive Order 8802 to end discrimination in defense industries. This order, which also established the Fair Employment Practices Committee to investigate incidents of discrimination, impacted women throughout the United States.

WHEREAS it is the policy of the United States to encourage full participation in the national defense program by all citizens of the United States, regardless of race, creed, color, or national origin, in the firm belief that the democratic way of life within the Nation can be defended successfully only with the help and support of all groups within its borders; and

WHEREAS there is evidence that available and needed workers have been barred from employment in industries engaged in defense production solely because of consideration of race, creed, color, or national origin, to the detriment of workers’ morale and of national unity:

NOW, THEREFORE, by virtue of the authority vested in me by the Constitution and the statutes, and as a prerequisite to the successful conduct of our national defense production effort, I do hereby reaffirm the policy of the United States that there shall be no discrimination in the employment of workers in defense industries or government because of race, creed, color, or national origin, and I do hereby declare that it is the duty of employers and of labor organizations, in furtherance of said policy and of this Order, to provide for the full and equitable participation of all workers in defense industries, without discrimination because of race, creed, color, or national origin;

And it is hereby ordered as follows:

1. All departments and agencies of the Government of the United States concerned with vocational and training programs for defense production shall take special measures appropriate to assure that such programs are administered without discrimination because of race, creed, color, or national origin;

2. All contracting agencies of the Government of the United States shall include in all defense contracts hereafter negotiated by them a provision obligating the contractor not to discriminate against any worker because of race, creed, color, or national origin;

3. There is established in the Office of Production Management a Committee on Fair Employment Practice, which shall consist of a Chairman and four other members to be appointed by the President. The Chairman and members of the Committee shall serve as such without compensation but shall be entitled to actual and necessary transportation, subsistence, and other expenses incidental to performance of their duties. The Committee shall receive and investigate complaints of discrimination in violation of the provisions of this Order and shall take appropriate steps to redress grievances which it finds to be valid. The Committee shall also recommend to the several departments and agencies of the Government of the United States and to the President all measures which may be deemed by it necessary or proper to effectuate the provisions of this Order.

Franklin D. Roosevelt

The White House,

June 25, 1941

DOCUMENT 4

Speech, President Franklin D. Roosevelt, “A Date That Will Live in Infamy,” December 8, 1941

On December 7, 1941, the day of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, President Franklin D. Roosevelt met with military advisors and dictated to his secretary, Grace Tully, a request to Congress for a declaration of war. He composed the speech in his head and revised a typed draft, notably changing the first and most famous line. The next afternoon, Roosevelt addressed a joint session of Congress, which was broadcast to the nation via radio. The Senate responded with a vote to support the war, and later that afternoon Roosevelt signed the official declaration of war. The reading copy of the speech, which Roosevelt left behind in the House chamber, was misfiled and “lost” for forty-three years. It was discovered in a file by a National Archives staff member in 1984. This declaration put into motion one of the largest mobilizations in US history, one that directly affected millions of women.

Yesterday, Dec. 7, 1941—a date which will live in infamy—the United States of America was suddenly and deliberately attacked by naval and air forces of the Empire of Japan.

The United States was at peace with that nation and, at the solicitation of Japan, was still in conversation with the government and its emperor looking toward the maintenance of peace in the Pacific.

Indeed, one hour after Japanese air squadrons had commenced bombing in Oahu, the Japanese ambassador to the United States and his colleagues delivered to the Secretary of State a formal reply to a recent American message. While this reply stated that it seemed useless to continue the existing diplomatic negotiations, it contained no threat or hint of war or armed attack.

It will be recorded that the distance of Hawaii from Japan makes it obvious that the attack was deliberately planned many days or even weeks ago. During the intervening time, the Japanese government has deliberately sought to deceive the United States by false statements and expressions of hope for continued peace.

The attack yesterday on the Hawaiian islands has caused severe damage to ...