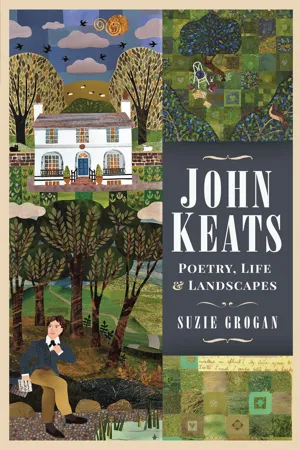

![]()

SECTION 1

IN KEATS’S FOOTSTEPS

![]()

1

Who are we following? John Keats: image or imagination?

Even if we are, as we turn these pages, only metaphorically following in the footsteps of John Keats, we need to make some attempt to recognise him, before he gets lost in the crowded streets of central London, or takes a turning across a Hampstead field we are unfamiliar with.

I have written a blog post for The Wordsworth Trust, called ‘Picturing John Keats’, originally published on my own blog with the subtitle ‘Image or Imagination?’. The response received has given me great pleasure, and reinforced my belief that, whether independent scholar, academic or reader for simple pleasure, we all form a picture in our minds of the person behind the words. Indeed, forming that picture should be encouraged, to ensure we do not lose sight of their existence in the real world, with all the heartaches, happiness and mundanity that involves. With John Keats, we are fortunate. His own letters give us clues, his friends wrote of him to each other in later years and we have portraits, miniatures and life and death masks to offer a physical appearance.

So who is ‘our’ Keats, as we read on?

John Keats has been viewed by many as the very picture of the Romantic poet, destined to die poor and at a young age. He was a man who attracted a devoted group of friends who in many ways promoted that image after his death. Disgusted at the treatment he received from prominent literary critics of the early nineteenth century, some suggested that his constitution had been weakened by these attacks. Shelley wrote the poem Adonais, portraying Keats as victim; Byron, hugely popular at the time and disliked by Keats, wrote disparagingly of him as ‘snuffed out by an article’ and later in the nineteenth century Oscar Wilde, in his poem On the Grave of Keats still spoke of him as a martyr. Thus the perception of Keats as the archetypal frail, sensitive poet became enshrined in nineteenth and early twentieth-century consciousness.

John Keats was born in 1795, the eldest son of the manager of the Swan & Hoop stables and inn, Moorgate, now on the main route into the City of London. It was a status in a class-ridden poetic society rather cemented by his qualification as an apothecary (still seen as ‘trade’) than improved, and ‘class’ would be an arrow aimed regularly at him by critics and poets such as Byron. He would not have spoken with the public school or theatrical accent used by most of the readers of his work to be found on YouTube, but with an accent undoubtedly influenced by his parents and those working in the stables around him.

We don’t have any paintings or sketches of him as a child so it is hard to visualise him crossing the fields of Enfield and Edmonton, walking to Clarke’s School or home to his grandmother Jennings’s house. However, later descriptions of his school days suggest he was muscular and small. He would never grow much above five feet tall, which pained him at times, but it never prevented his being ready to ‘fight anyone morning noon and night’, as a schoolboy contemporary, Edward Homes recalled. Keats was well known as having a quick temper and always ready to fight his, or another boy’s, corner.

Similarly we cannot see him as a teenager, undertaking his apprenticeship with Thomas Hammond, Apothecary, of Edmonton. It was an unhappy period of his life and having lost both his father and more recently his mother, he was a challenging pupil. As he left his teens, though, and during his period as a medical student, he had clearly matured into a striking young man, attractive to women. Caroline Mathew, sister of an early poet friend George Felton Mathew saw him as ‘ebullient and outgoing’, with a ‘fine flow of animal spirits’ and a ‘very beautiful countenance’. His character was ‘warm and enthusiastic’ and there is a suggestion of a brief romance between the two. Her brother George thought that ‘a painter or sculptor might have taken him for a study after the Greek masters’.

At about the same time, however, as he struggled to develop a poetic voice whilst continuing his studies at medical school, he wrote a sonnet that begins:

Had I a man’s fair form, then might my sighs

Be echoed swiftly through that ivory shell

Thine ear, and find thy gentle heart; so well

Would passion arm me for the enterprize;

But ah! I am no knight whose foeman dies;

No cuirass glistens on my bosom’s swell;

I am no happy shepherd of the dell

Whose lips have trembled with a maiden’s eyes.’

This does not suggest confidence or arrogance about his appearance. Whilst he may have adopted a characteristically ‘poetic’ form of dress, growing a moustache, turning down his collar and tying a ribbon around his neck ‘à la Byron’ (as opposed to the current fashions for high collars and neckerchiefs) he was clearly still self-conscious and unaware of the charisma that drew so many to him. Later, he would often analyse his complex relationship with women, writing with similar self-deprecation to Benjamin Bailey, 18-22 July 1818, ‘I do think better of Womankind than to suppose they care whether Mister John Keats five feet hight [sic] likes them or not.’

Henry Stephens (later the inventor of the famous ink of the same name) lodged with Keats when studying medicine and later recalled that Keats was ‘swift-witted’ and offered an early physical description. Keats had a ‘thin face, prominent cheekbones, well-formed nose and receding forehead’. He considered his look ‘more of the Poet than the Philosopher’. This was generous from a man who later wrote disparagingly of Keats as medical man and poet, perhaps influenced by the fact that Keats passed his exams first time whilst he did not.

Later we will follow ‘swift-witted’ but ‘aloof’ Keats, with chin raised, fluffy moustache on his top lip and large observant eyes, around the wards of Guy’s Hospital and there we will see a young man barely out of his teens against a backdrop of some kind of hell. Keats was intense and acutely sensitive and alive to the world but he was not ‘unworldly’. Training as a doctor at Guy’s Hospital, when surgery was in its infancy and savage to a degree we can barely imagine, he would have witnessed suffering that intensified feeling and offered grim source material for his later poetry. We won’t be watching a young man likely to be rendered incapable of coping with the barbs thrown at him by the press, however angry he may have felt.

At this point, it is tempting to wonder how Keats spoke. Of course, unlike the scratchy recordings we have of other nineteenth century poets such as Tennyson, we have nothing to even hint at his real voice. Recent readings of his poetry by famous actors, available on YouTube, for example, tend to the plummy ‘posh’ or RADA pronunciation. Benedict Cumberbatch and Tom Hiddleston, for example, offer wonderful readings in mellifluous tones, but they surely do not sound like a young man in his early twenties from a pub in central London. An interesting article in the New York Times of October 2009, by Micah Lidberg, reflects on this very topic in light of the then newly released film Bright Star, directed by Jane Campion. Like Lidberg, I was struck by how like the dialogue of the period the script was; it was presented in an authentic way by the lead actors, Ben Whishaw as Keats and Abbie Cornish as Fanny Brawne. Some of what Keats says comes from his letters, and as Lidberg points out, Campion peppers the script with references and words that Keats himself uses, even as she puts them in the mouths of other characters.

Harsh critics accused Keats of ‘Cockney rhymes’, and we could, therefore, assume a cockney accent, especially as some of his spelling suggests he is writing, obviously quickly and conversationally, as he speaks. However, as Lidberg points out, other poets such as Blake and Tennyson used similar examples which suggests that with an ear for dialect, Keats would have made sure he was not embarrassed in his many and varied conversations with his peers. He himself wrote of identifying with others present in any room he entered.

A friend once commented that Keats read his own poetry badly, but others found his readings captivating, ‘tremulous’. I have to admit that my favourite recitals of the poems are by Ben Whishaw, as Keats. He seems to me to have adopted an unaffected tone, without unnecessary theatricality, pomp or drama. Of course, this is all imagination; we will never know.

As yet, we do not see a frail archetype. Later, written descriptions of Keats are offered by a number of friends and acquaintances in the ‘Keats Circle’ and not one of them suggests frailty or weakness. The poet Barry Cornwall (real name Bryan Procter) claimed he had ‘never met a more manly and simple young man’. Charles Brown, the close friend with whom he lived for much of his writing life, described him as ‘though thin, rather muscular’. He had auburn or brown hair and hazel eyes and a ‘peculiarly dauntless expression’, Joseph Severn noted, all ‘trembling eagerness’. His Oxford friend, Benjamin Bailey, like Mathew, considered ‘… the form of his head was like that of a fine Greek statue’. Others suggested he had an ‘inward’ contemplative look. These, I think, are those later remembered memories that idealised Keats; as Stanley Plumly says in the marvellous Posthumous Keats, the descriptions were ‘postponed, elevated or distorted by memory, even grief’. Poet Andrew Motion, Keats’s biographer, suggests that all these descriptions amount to a picture of a man at once ‘feminine and robust’.

As a younger reader, I was not familiar with these descriptions, and ‘my Keats’ was influenced by the images available in books, or on display at Wentworth Place (now known as Keats House) in Hampstead. Of course, we are now allowed even greater access via many internet sites, but in addition to the classic poses, we are offered any number of weakened imitations, produced posthumously and infected with that ‘ideal’ of the sensitive and ‘poetic’, the ‘Romantic’. There are some hideous offerings; some are rotated, or reimagined by fans and professionals alike, suggesting Keats looked anything from twelve to perhaps forty. Some are given the wrong attribution, and to add to the confusion some are labelled incorrectly – we have pictures of Shelley or Byron as Keats.

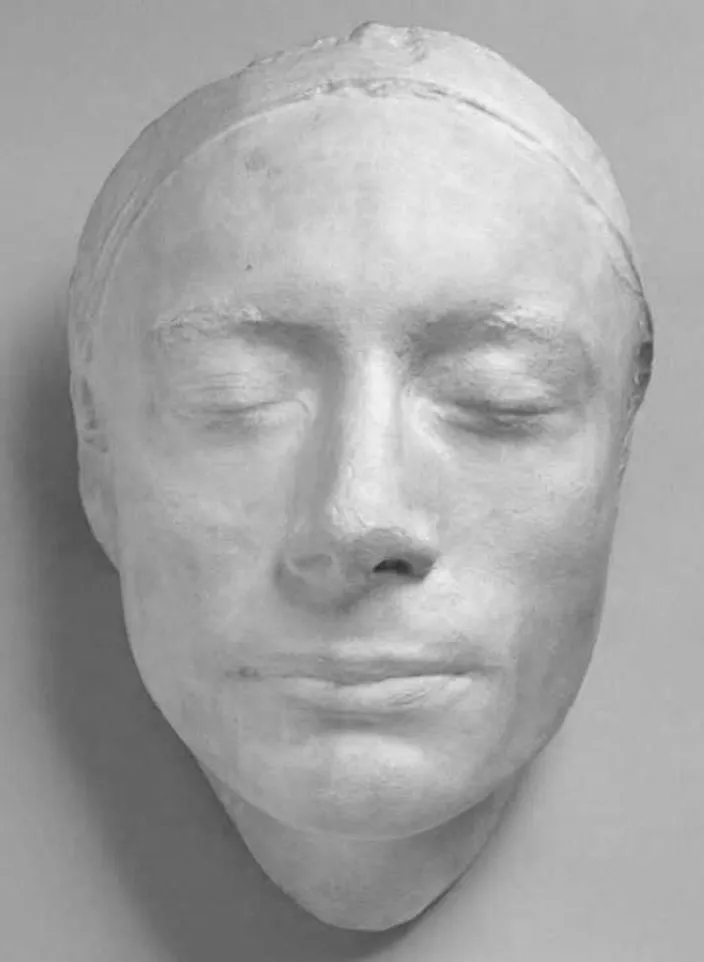

Those first impressions, as I walked around the as-yet-unrestored house in Hampstead, have the most meaning for me and it is an excellent place to get to know the real Keats even now. One of the most affecting images was the life mask taken of him by artist Benjamin Robert Haydon in December 1816, when Keats was just 21. Nicholas Roe, in his biography Keats, describes the process by which the life mask would have been taken. It was not for the faint-hearted. The ‘hair was swept back under a towel and tight about the ears and neck. With his skin greased, eyes and mouth shut and breathing through straws in his nostrils, he felt Haydon apply the cold, clammy plaster.’

He would have to remain still for several hours as the plaster gradually set, but the result is wonderful. It shows the sunken cheeks and the strong features of the descriptions, and his mouth, though by necessity tightly closed, indicates that top lip protruding slightly over the lower. John’s sister, Fanny, loved it, although she was disappointed with the mouth and of course there is no sense of the eagerness and vitality in his eyes (although they are clearly large) or the colour of his skin, or hair. Roe describes the face as full of ‘power and serenity’; I saw, and see, a beautiful young man, strong and firm of feature.

Keats life mask, by Benjamin Robert Haydon, 1816. (National Portrait Gallery NPG 686)

Keats, by Joseph Severn, 1817. (Victoria and Albert Museum F.90)

There is a charcoal sketch from about the same time, made by friend Joseph Severn. I have a poster of this image from the Keats-Shelley House in Rome looking down on me as I write and can appreciate why it was a favourite amongst his friends – Charles Cowden Clarke describing it as ‘most perfect’. It reflects the face in the mask but is so much more animated and full of intention and indicates that at this time he wore his hair long, in natural curls. This look is replicated in Benjamin Robert Haydon’s sketch of Keats for his monumental Christ’s Entry into Jerusalem, a painting which features many famous contemporaries in the crowd. It wasn’t exhibited until 1820, after Keats’s first major haemorrhage. It must have been a chilling reminder to his friends of how vital and alive the man once was.

In 1819, Severn painted a famous miniature of Keats which has been much copied and re-interpreted, not least by William Hilton, a contemporary of Keats. The two portraits show a man at once young and earnest and at the same time, in the Hilton especially, more powerful and certain of his place in the pantheon of great poets. I have never liked the miniat...