![]()

1

Ivan Aguéli: Politics, Painting, and Esotericism

Mark Sedgwick

The life of Ivan Aguéli (1869–1917) takes us through some of the most important territory of the late nineteenth century. Born in Sweden, where he first encountered the Western esoteric tradition, Aguéli spent much of his adult life in the French avant-garde milieu. Settled in Paris, he painted, wrote, read, and spent time in jail for revolutionary offences. After converting to Islam in 1898, he moved to Cairo, where he was known as ‘Abd al-Hadi. He became a Sufi, and his translations from Arabic into French at the start of the 1910s introduced the work of the great mystic theologian Muhyiddin ibn ‘Arabi (1165–1240) to the Parisian esoteric milieu. It was also Aguéli who introduced the turn-of-the-century French philosopher René Guénon (1886–1951), founder of the Traditionalist movement, to Sufism and Islam.

Aguéli is notable as one of the earliest Western intellectuals to convert to Islam and to explore Sufism, and he is also notable as an artist, an anarchist, and an esotericist. This book treats all these different aspects of his life and activities, exploring various facets of his complex personality in their own right, and also showing how they all fitted together—how, in the end, esotericism, art, and anarchism found their fulfillment in Sufism.

Aguéli’s life and conversion show that Islam occupied a more central place in modern European intellectual history than is often realized. His life reflects several major modern intellectual, political, and cultural trends, some better studied and understood than others. As is well known, the late nineteenth century saw many groundbreaking painters, much radical politics, widespread interest in esoteric alternatives to Christianity, and growing knowledge (accurate or inaccurate) of the “Orient.” Aguéli, however, was one of only a very few Europeans to synthesize these trends into what was then still a very unusual destination: conversion to Islam.

This synthesis was idiosyncratic, but not unique. Echoes of parts of it, and occasionally all of it, are found in other individuals and in later periods, especially in the Traditionalist movement that derived in part from Aguéli, and that later adopted Aguéli as one of its canonical figures. Although apparently disparate, all the movements with which Aguéli engaged had something in common. Esotericism overlapped with art, as artists turned to the esoteric for help in their quest to see the world a new. Progressive and revolutionary approaches to art combined comfortably with progressive and revolutionary approaches to politics, and hence with anarchism, which in turn combined with resistance to colonialism. Resistance to colonialism encouraged a sympathetic approach to Islam, as so many of those suffering from the effects of colonialism were Muslim. Western esotericism also encouraged a sympathetic approach to Islam, since the apparently pure monotheism of Islam appealed to many who had rejected the Christian churches and Christian myth and doctrine but still hoped for access to the transcendent. Western esotericism also combined comfortably with the Islamic esotericism of Ibn ‘Arabi, and thus with Sufism. Many, then, combined art with esotericism, art with anarchism, or esotericism and anarchism with sympathy for Islam and Sufism. Aguéli combined all of these.

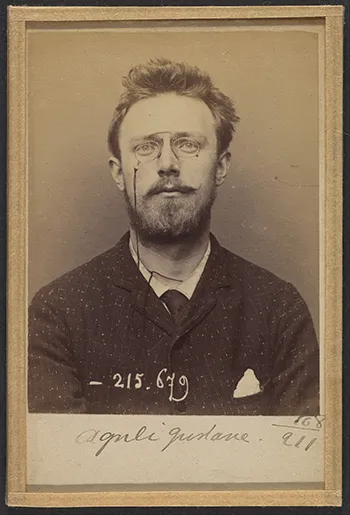

Figure 1.1 French police photograph of Ivan Aguéli, March 1894. Made by Alphonse Bertillon. Albumen silver print from glass negative, 10.5 x 7 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gilman Collection, Museum Purchase, 2005.

Aguéli’s Life

Ivan Aguéli started life in provincial Sweden as “John Gustaf Agelii,” but was known under a succession of different names that marked successive phases of his life. He replaced “John” with its Russian equivalent, “Ivan,” in 1889, when he was twenty, probably under the impact of his enthusiasm for the Russian literature he was then reading; this change was associated with the transition from his problematic schooldays to his first years as an artist in Sweden. The next change, when he replaced “Agelii” with “Aguéli,” marked his emigration from Sweden to France, which after 1892 became his primary domicile; not only does “Aguéli” look more normal in French than “Agelii,” but it is also easier to pronounce, and follows the rules of French orthography.1 The final change, to ‘Abd al-Hadi, marked his conversion to Islam and subsequent move from France to Egypt, in 1902; often he signed articles as “Abdul Hadi El-Maghrabi,” a pun, as although “al-Maghrabi” is a fairly common surname in Egypt, its literal meaning is “the westerner,”2 and Aguéli was, indeed, a Westerner. Egypt replaced France as his primary domicile, although he did spend 1909–13 back in France, and was expelled from Egypt by the British authorities, who suspected him of opposing their war effort, in 1916. After taking the first available ship to Europe, he was stranded penniless in Spain, where in 1917 he was run over by a train.

It was as a young man in Sweden that Aguéli (or Agelii, as he was known then) first encountered esotericism in the form of the work and followers of the Swedish Christian visionary and mystic Emmanuel Swedenborg (1688–1772). Swedenborg was a visionary in that his life was transformed by a series of visions of angels that inspired his later work, and a mystic in that he emphasized the transcendent reality (or “spiritual world”) of which the “earthly world” is a reflection, the connection of the human soul (“inner self”) to transcendent reality, and the central role of divine light (“heaven’s light”).3 Similar understandings, which may be termed emanationist (the earthly world “emanates” from transcendent reality), are found in many other thinkers and traditions, and may be traced back to Plato, or alternatively to the later Neoplatonic philosophers, of which Plotinus (died 270) is the most important.4 This understanding and genealogy of mysticism is not the only one possible, and has indeed recently been subjected to much criticism,5 but it is the most useful one in this context, as it is the scholarly version of the understanding to which thinkers from William Blake (1757–1827) to Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803–82), and from Aguéli to Kathleen Raine (1908–2003), subscribed.

Swedenborg’s followers never became numerous, but founded what came to be known as the New Church. After moving to Stockholm in 1888, Aguéli became friends with the family of a pastor of the New Church, Adolph Boyesen (1823–1916).6 Swedenborg was to remain of great importance to him throughout his life, and is discussed in many chapters in this book.

In Paris, Aguéli encountered a new form of esotericism, that of the Theosophical Society, and a new political engagement, with anarchism. The Theosophical Society had been established in New York in 1875 by Helena Blavatsky (1831–91), and by the time that Aguéli joined, it had become a global organization with headquarters in Adyar, near Madras (now Chennai), in India. Blavatsky, who had become a Buddhist, claimed to be in communication with hidden spiritual masters known as Mahatmas, but in fact drew on Neoplatonism, on the Western Hermetic-Kabbalistic esoteric tradition, and on understandings of Buddhism and Hinduism in her own writings,7 which were supplemented by the writings of many other Theosophists in a variety of books and journals. The teachings of the Theosophical Society were eclectic, and also broad: there was no central official creed that had to be adhered to. The Theosophical Society also had a political agenda, aiming at the “universal brotherhood of humanity,” which in practice often meant opposing European colonialism.8 The Theosophical Society, then, was important for its teachings and its reinterpretation of religious myth, and for the social and organizational framework it provided for the investigation of a variety of religious and spiritual ideas. It was not a major source of social identity for most of its members, as there was no need to “convert” to Theosophy away from any other denominational allegiance. It had little or no ritual.

The political agenda of Anarchism was much more radical than that of the Theosophical Society. It was part of the large family of political theory that can be described as socialist, but differed from the parliamentary or “democratic” forms of socialism that later became dominant in Western Europe, and from the Marxist-Leninist forms of socialism that later became dominant in Eastern Europe, in that rather than seeking to use the state, it saw the state as a major part of the problem. Even though “anarchy” is now generally understood as meaning “chaos,” the anarchists aimed at social justice, not chaos. Some of them used what was then called “propaganda of the deed” and is now called “terrorism” to promote their cause, resulting in a popular association between anarchism and terrorism, and even between terrorism and chaos. This, however, again misrepresents anarchism. Aguéli came to subscribe to anarchist theory and anarchist ideals; he was also close to Parisian anarchists who used propaganda of the deed, which is how he came to be arrested in 1894. The police photograph taken of him after his arrest is shown as Figure 1.1.

As well as encountering Theosophy and anarchism in Paris, Aguéli also became friends with a prominent animal-rights activist (and anarchist), Marie Huot (1846–1930, Figure 2.4). Huot was twenty-three years older than Aguéli and married; in what sense the relationship between her and Aguéli was romantic is unclear, but it was extremely close, and of lasting importance.

One of the most celebrated French painters of the period, Paul Gauguin (1848–1903), spent 1891–3 painting in Tahiti, and this was one reason that Aguéli began a series of trips outside Europe, starting immediately after his release from prison. He spent 1894–5 in Egypt and, in 1899, traveled to Colombo in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka). In 1898, under unknown circumstances, he converted to Islam; he had been studying Arabic and the Qur’an for many years. At this time, the Swedish painter Fritz Lindström (1874–1962) portrayed Aguéli in Muslim style in his 1898 painting “Ivan Aguéli”, now in the National Museum, Stockholm.

Soon after his return to France from Ceylon via India, Aguéli gained fame in France after one of the earliest and most successful acts of animal-rights activism. Huot had already used the propaganda of the deed in her campaign against vivisection, interrupting a lecture by Louis Pasteur (1822–95) in 1886, and on another occasion beating the physiologist and neurologist Charles-Édouard Brown-Séquard (1817–94) with a parasol. In 1901, she and Aguéli went to a bullfight in Deuil, a little to the north of Paris, where Aguéli fired at the bullfighters as they arrived at the bull-ring. No-one was killed, but one Spanish bullfighter was wounded. Public opposition to bullfighting, and thus support for Aguéli, reached the point where Spanish-style bullfighting was banned in France. At his trial, which took place in an atmosphere more favorable to Aguéli than to the wounded bullfighter, who had returned to Spain and did not appear, Aguéli was sentenced to pay a small fine and given a suspended sentence, even though he was arguably guilty of attempted murder.

The following year, in 1902, Aguéli moved to Cairo, where he assisted an Italian friend, Enrico Insabato (1878–1963), in publishing and writing for a bilingual Arabic-Italian periodical, Il Convito/Al-Nadi. Insabato’s objective in publishing this journal was to promote the image of Italy as a friend of the Arabs and Islam; Aguéli’s objective was probably to promote Islam and to oppose colonialism. Aguéli’s articles in Il Convito/Al-Nadi are discussed in several chapters of this book.

One of the Egyptians who wrote in Il Convito/Al-Nadi was ‘Abd al-Rahman ‘Illaysh (1840–1921), who helped Aguéli read classic Islamic texts, including some by Muhyiddin ibn ‘Arabi, the preeminent mystical writer of the Sufi tradition, and who admitted Aguéli into a Shadhili ṭarīqa (Sufi order). Sufism is often described as the mystical branch of Islam, and it is true that the greatest interest in the Arabic-language mystical philosophy and theology that resembles the thought of Swedenborg and can be traced back to the Arab and Islamic reception of Plotinus and other Neoplatonists is to be found among Sufis. Not all Islamic philosophers are Sufis, however—some are just philosophers—and most Sufis are not philosophers. Sufism is a major tradition of practice across the Muslim world, generally organized into lineages and groups known as ṭarīqas (a term normally translated as “order”), most members of which were, until the recent development of mass education, illiterate. Sufism itself has an important literature, but for most Sufis, ascetic practice and the example of the shaykh or spiritual guide has been paramount. ‘Illaysh became Aguéli’s shaykh.

Although a major tradition of practice across the Muslim world, at the start of the twentieth century Sufism was under attack from a rising group of modernist reformers, who tended to dismiss it as superstitious and obscurantist. ‘Illaysh was associated with the religious establishment based around al-Azhar, Egypt’s preeminent mosque and madrasa (later modernized into a state-run university). Aguéli thus stood with the traditionalist religious establishment against modernist reform.

Aguéli’s Context

Aguéli was not the only Western Sufi of this period. There was a long-standing interest in Sufism in Western Europe, going back to the beginnings of modern Orientalism. It can be dated to the publication in 1671 of the first translation of a Sufi text to be widely read in Western Europe, the Hayy ibn Yaqzan of Ibn Tufayl (1105–85), translated by Sir Edward Pococke (1604–91), the first ever professor of Arabic at the University of Oxford, and his son. The Hayy ibn Yaqzan was generally regarded as an expression of Deism, not of Sufism,9 but Sufism and Deism were then enduringly connected in Western Europe (and later the Americas) by another great British Orientalist, Sir William Jones (1746–94), in an important lecture given in 1789.10

Though there were Sufi texts in Western Europe during the eighteenth century, there were no Western European Sufis;11 post-Christian and non-Christian religious organizations (other than Jewish ones) were not established in Western Europe and America until the nineteenth century. The most important of these was the Theosophical Movement. Blavatsky and the Theosophists emphasized Buddhism, not Sufism, but one American who was active in Theosophical circles was interested in Sufism, and a Sufic Circle was established in America in 1887, though it did not develop enough to leave any mark on the historical record.12 During the 1890s, a German resident in Turkey, Rudolf von Sebottendorf (1875–1945[?]), seems to have joined the Bektashi ṭarīqa, though details are few; Sebottendorf later wrote a book on his rather occultist understanding of Sufism, published in Germany by the press of the German branch of the Theosophical Society in 1924.13 An American, Ada Martin (1871–1947), became a Sufi in San Francisco in 1911; her Sufi master, an Indian, Inayat Khan (1882–1927), published his first book in English on Sufism in London in 1914. Again, this was published by the local branch of the Theosophical Society.14

The historical circumstances that lie behind Aguéli’s Sufism, then, include the growth of alternative religious thought and of Orientalism during the eighteenth century, and the growth of alternative religious organizations, notably the Theosophical Society, during the nineteenth century. Behind these developments lie the Enlightenment, the Industrial Revolution, and the decline of the hegemony of the Christian churches, without which the developments in first religious thought and then religious organization could not have happened. Globalization and imperialism were also important, as these led to the increased availability of Oriental and Sufi texts in Western Europe, and then to the facility with which people like Aguéli, Gauguin, Sebottendorf, and Inayat Khan could travel around the world. When Pococke, the English translator of the Hayy ibn Yaqzan, traveled to Syria in 1630, the journey was a long and dangerous one by a sail ship; when Aguéli visited Ceylon, he bought a ticket on a steamship that followed a timetable.

Traditionalism

After the closure of Il Convito/Al-Nadi and the departure of Insabato in 1907, Aguéli returned to France between 1909 and 1913, partly for lack of money—he spent almost the whole of his life in severe financial difficulties. Back in Paris, he met the young French philosopher René Guénon, and in 1910–11 wrote in...