![]()

On stage is a Bible, a half bottle of whiskey and a piano with a metronome on top.

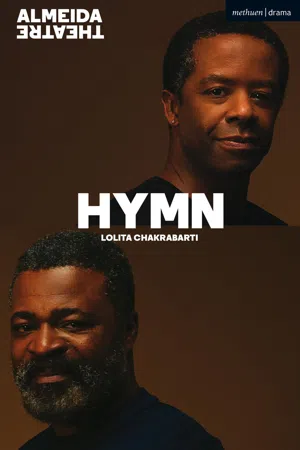

Two actors, male, 50, black, enter. They both wear black face masks. They start the metronome, regard the audience and consider the objects.

One actor picks up the Bible. He will play Gil.

The other picks up the bottle. He will play Benny.

In silent agreement the two men remove their masks.

It begins.

Benny What the hell . . .! Get off me! Mooove your fuckin’ hands . . .!

The sound of breaking glass, a tussle and the metronome stops.

Benny, very drunk, is thrown out of a pub. A door slams.

A street

January.

That’s not nec-ess-ary. NOT NECESSARY! Y’ave to ask nicely man! Been a shit day, I jus’ wanna drrrink. People to stan’ next to. You want the custom not the custom-errr. Don’t care ’bout meee, as long as I Pay My Way, cost you nothin’. But how long can any of us do that? Y’ever done a jigsaw mate? I’m tellin’ you, you’re missin’ some crucial fuuuckin’ pieces and I should know! And here’s a gift, if you try a right hook, get your staaance sorted or you’ll never connect, and you’ll just be ano-ther mug punchin’ air.

You owe me maaan! I’ve invested hard cash in your shit-hole, my money’s in your jukebox and I’ve not got what I paid for. I’m not leavin’! I wan’ wha’s mine! I’ll stay right here and finn-ish my juiice!

He brings out the bottle of Scotch as someone passes by.

What you lookin’ at? You don’t know me. I’m not what any of us thought. Your burger’s drippin’ and I’m tellin’ you, you won’t get that oil outta them jeans. Dinnner and a show. I thank you. Now fuuuck off!

As he takes a bow he stumbles but protects the bottle.

Steady as she goes! What you gonna do tomorrow, Benny? She laid it down. D’you pick it up? Tha’. Is. The. Question.

Gil, at the piano, plays the opening chords of ‘Lean on Me’ (Bill Withers).

There it is! My man! My tuuuune! Music to stan’ next to.

Benny animates his bottle of scotch as if it is singing to him. He sings the chorus . . .

‘Lean on me, when you’re not strong . . .’

Bet you’re watchin’ me. Always lurkin’ in the shadows out o’reach. I got twelve hours. Do it Benny boy, no-one neeeed know. My head’s spinnin’. No son, the world’s spinnin’ and you’re in the saaame place you aaalways were.

Church

The next morning.

Gil sings the next verse of ‘Lean on Me’ (Bill Withers) with the congregation.

Gil

‘Please swallow your pride . . .’

Gil steps up to the podium with his Bible to speak.

That was Dad’s favourite. He played it for Mum at their golden wedding anniversary and asked her to dance. They were so devoted. You could feel it.

Gil opens his Bible.

This was Dad’s favourite too – ‘Praise the Lord. Praise God in his sanctuary; praise him in his mighty heavens . . . for his acts of power . . . his surpassing greatness. Praise him with the sounding of the trumpet . . . with the harp and lyre . . . with the strings and pipe, praise him with the clash of . . . resounding cymbals’. I can see him now, nodding his head, eyes closed, as though listening to heavenly music.

Gil brings out some handwritten pages and regards the large congregation.

Augustus Clarence Jones was born eighty-six years ago in St Mary, Jamaica. He married our mum just before they came here in 1960 and rented a room in a house on George Road. They saved and saved and eventually bought that house where they’d have four kids who gave them eight grandchildren. George Road is our family home and Cleo, Diane, Sweetie and me made sure it was well lived in. Dad, a tailor by trade, ‘a master of cloth’ Mum used to say, turned his hand to everything – plastering when I put a hole in the bathroom wall, woodwork when Sweetie broke Mum’s sideboard, metal work when Cleo jammed the front door key in the lock. Diane of course didn’t do things like that. He also made my first communion suit by hand. Every cut, every stitch was his. A man of many talents.

He worked alone in the back of his first dry cleaning shop on the High Street. When he came home to the shouting and tears, the records and TV, the shrill conversation and door slams he rarely raised his voice but when he did, all sound stopped. That was Dad. I once asked him how he could stand it. My sisters were driving me mad. It was one of the few man-to-man talks we had. He said all he heard was music. He said ‘Gilbert, music is silence, sound and time. If you listen son, you’ll hear it too.’ A master of cloth and a bit of a poet then. An impressive figure of a man in his trilby hat and gold tie pin. That was Gus.

Gil puts away his pages to speak from the heart.

Dad called this church the Big House where he was just one of the kids. He loved to sing here. I used to squirm when his voice boomed across these aisles, rarely in tune, sliding in and out of the melody. I was ten, eleven and Mum would cut her eyes at me not to laugh. But he never cared, he just sang louder.

He worked so hard, built everything from the ground up, bought his first business and...