1

Monasteries

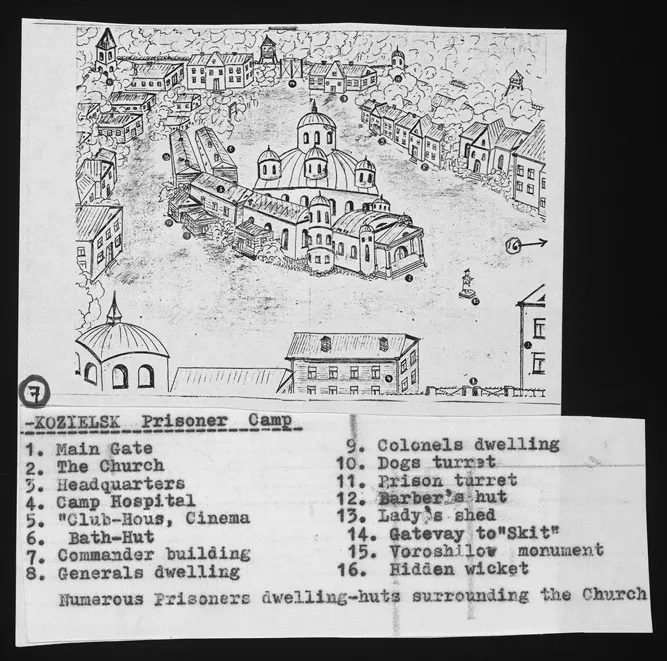

In the distance, on the left side of the road, a high long wall glistened white. Silhouetted against the sky behind the wall were the rooftops of a number of buildings dominated by the bulbous outline of a dark blue church cupola. As we approached the wall, we saw that it was reinforced on the outside by a high barbed wire abatis and dotted with many wooden mushroom-shaped towers inside which we saw machine guns and huge searchlights.1

Since 17 September the Red Army had captured between 230,000 and 240,000 members of the Polish military, including around 10,000 officers. The army had no expertise in dealing with large numbers of prisoners or in running prison camps, so the task was entrusted to the only Soviet organisation capable of operating on such a vast scale: the NKVD. Within two days of the invasion preparations were in place: on 18 September NKVD Convoy Troops were put on a war footing and instructed to take charge of the reception points to which the Polish prisoners of war were being taken. On 19 September the head of the NKVD, Lavrenty Beria, ordered the establishment of the Administration for Prisoner-of-War Affairs, or UPV (Upravlenie po Delam Voennoplennykh), to be run by NKVD Major Pyotr Soprunenko under the supervision of Beria’s deputy and close colleague, Vsevolod Merkulov. Regimental Commissar Semyon Nekhoroshev was to act as the UPV’s commissar. A total of fourteen prison camps were made ready to receive Polish prisoners of war. Of these, seven were transit camps, four were labour camps and three – Kozelsk, Starobelsk and Ostashkov – were designated as special camps where officers, prominent state and military officials, intelligence agents, counter-intelligence agents, gendarmes, prison guards and police would be held. Each camp was situated in a different region of the Soviet Union: Kozelsk lay 200 miles south-east of Smolensk in Russia, Starobelsk in the eastern part of Soviet Ukraine about 150 miles from Kharkov, Ostashkov lay 150 miles west of the city of Kalinin (now Tver) in Russia’s freezing north.

Higher-ranking and staff officers were to be sent to Starobelsk; police and prison guards to Ostashkov; privates from the German part of Poland were to be divided between Kozelsk and Putyvl camp in Ukraine. When it became obvious that Starobelsk could not hold all the officers, several thousand were sent on to Kozelsk, which thus became an officer camp.2

Given the sheer number of Polish prisoners captured by the Red Army, the Politburo swiftly decided that privates and non-commissioned officers would be released and sent home. In civilian life these (mainly young) men were labourers, drivers, agricultural or factory workers; they were of no strategic or political interest to the Soviet authorities. Since it was impossible to separate officers from men effectively in the field the process of sorting took place within the camps themselves. As a result, between early October and mid-November thousands of men arrived in the three special camps only to be sent back home again, in some cases returning on the train in which they had just arrived. Residents of the Soviet zone of occupation went first, followed by those whose homes were in German-occupied territory, who were handed over to the German authorities in a prisoner exchange. Others were sent to work on roads and in mines within the Soviet Union. The chaos of those first weeks is hard to overestimate: on 14 October 1939 Starobelsk camp held over 7,000 men, including 4,813 privates and NCOs, 2,232 officers and 155 others. By 1 April 1940 there were 3,893 prisoners, almost all of them officers. In Kozelsk the camp population halved from a total of nearly 9,000, mainly privates, to 4,599, mainly officers. A total of 16,000 men passed through Ostashkov camp: after 9,400 privates and NCOs were released to the Germans and others transferred to work in the mines, the camp population settled at 6,364.3 It was not until mid-November that camp numbers finally stabilised and a routine was established.

The three camps were housed in former monasteries or convents whose occupants had been massacred during the revolution, their buildings then ‘repurposed’ for use by the NKVD. The sites bore grim witness to the violence of the recent past: in Starobelsk, formerly an Orthodox clerical seminary, tombs in the old graveyard had been uncovered; prisoners found skulls and bones buried in shallow earth in the grounds; bullet marks scarred the walls. Ostashkov camp occupied the remains of the magnificent Nilova Hermitage on Stolbny Island in Lake Seliger. Prisoners making repairs to the monastery cellars came across bones and scraps of fabric, even part of a gun. Two of the original monks had apparently survived and still worked there; one of them – ‘a tall man, with expressionless face and deep-sunken eyes [who] looked like a walking corpse’ – never spoke.4

Despite the NKVD’s fearsome reputation for efficiency, honed in running the vast network of Soviet labour camps known as the Gulag, camp commanders faced a considerable logistical challenge in financing and organising the provision of food, material and medical supplies for so many prisoners of war arriving simultaneously and at such short notice. Transports comprising hundreds of Polish officers and enlisted men streamed daily into camps which, despite hasty preparations, were in no fit state to accommodate them. In Kozelsk, construction of the bunks had only just begun when the first prisoners arrived; there was not enough straw for mattresses and a lack of sheets, blankets and pillows; a chronic shortage of brooms, cloths and bins made cleaning the camp next to impossible; while the toilets (inadequate in number) had no roofs or walls. Food supplies were unevenly distributed, with many essential items missing and an almost total lack of fresh food.

As to the matter of vegetables, the situation is bad indeed. We have enough potatoes for three or four days and now they are not bringing them to the camp, because the region did not complete a supply plan and all the local potatoes are being sent to Moscow. There is no cabbage at all and no hope of obtaining any.5

It was dusk when Bronisław Młynarski passed through the gates of Starobelsk, along with a group of around a thousand men. The only order they received on arrival, shouted by a revolver-wielding politruk from the steps of the church, was to find themselves somewhere to sleep for the night. Młynarski had managed to stick with his cheerful group of friends and together they went in search of shelter. Every building was already full to bursting, every spare inch of muddy ground occupied by men stretched out on coats or blankets. As darkness fell, bringing with it a penetrating cold, the friends decided to take a look inside the smaller of the two churches. It had already acquired a nickname: ‘the Circus’ (or, sometimes, ‘Shanghai’). Upwards of a thousand men lay on cramped bunks piled up to the ceiling on a precarious metal scaffold. On the floor sleeping men squeezed together like pilchards. The entire space reeked of unwashed bodies and dirt. A young reserve army doctor, Zbigniew Godlewski, arrived in Starobelsk in early October. He found the building so intimidating it was a month before he dared enter it:

The ranks and ranks of bunks, the darkness, the noise of people swearing and shouting. As soon as I entered some cried out: ‘Shut the door!’ while others shouted: ‘There’s no harm in a little fresh air.’ Immediately, I was asked whom I had come to visit. As I did not answer immediately, cries went up: ‘Look! A stranger’s come to spy on us. Something’ll go missing, that’s for sure. Or maybe he’s a sneak.’ I was swiftly surrounded by several people. Fortunately, I remembered the name of my acquaintance and they recognised me from chopping wood.6

Józef Czapski described the Circus as a strange and intimidating place, to be entered as one would a jungle. His close friend, the engineer Zygmunt Mitera, lived there, as did a lively group of students from the Academy of Arts in Warsaw and an avant-garde poet from Kraków, Lech Piwowar, who had married just a few weeks before the outbreak of war. In the centre of the church was a stage that had apparently been used for party and komsomol [Communist Youth League] meetings. Several prisoners slept underneath it, entering and exiting via the prompter’s box. The larger church building remained locked throughout their stay; rumour had it that it was used to store grain which was sent to the front to feed German soldiers. On the summit of its cupola was an Orthodox cross. ‘[It] did not reach upwards in a proud vertical line. Corroded at its base by the rust of time, it hung crooked and inert.’7

In the confusion created by the departure of the enlisted men some officers saw an opportunity. With registration yet to begin, restless young men weighed up their future prospects: was it worth the risk to try to escape?

Dr Zbigniew Godlewski’s journey to Starobelsk echoed that of many of the captive officers: after losing contact with his division when it came under German attack near Warsaw, the young doctor had wandered ever further eastward, tending to the wounded as best he could before eventually falling into the hands of the Red Army as he tried to escape home from Białystok. Separated from his friend and fellow medic, Barć, Godlewski spent his first night in the camp alone, falling fast asleep in a stone trough resembling a coffin, his army rucksack serving as a pillow. The following morning Barć reappeared carrying a bowl of lukewarm porridge which he had somehow – miraculously – managed to obtain from a kitchen somewhere within the crowded camp. Godlewski was delighted to be reunited with his friend but noticed Barć seemed agitated, scarcely able to conceal his impatience while Godlewski ate his breakfast. As soon as the porridge was gone Barć spoke. He had a plan, he declared: the enlisted men and NCOs from Ge...