eBook - ePub

Energy and Security in the Industrializing World

This is a test

- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Energy and Security in the Industrializing World

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Provides detailed analyses of the related concerns of energy needs, the economy, and national security for developing countries—Argentina, Brazil, Cuba, India, Pakistan, South Africa, South Korea, and Taiwan.

The essays serve to underline the dangerous problem of nuclear proliferation for several of these countries have uneasy relations with their neighbors. In their detailed reviews of these eight nations—their plans and their capabilities—the contributors have provided a valuable source for a neglected area of international affairs.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Energy and Security in the Industrializing World by Raju G. C. Thomas, Bennett Ramberg, Raju G. C. Thomas,Bennett Ramberg in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & National Security. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Relationships among Energy, Security, and the Economy

RAJU G.C. THOMAS

With the oversupply of oil on world markets and the fall in international oil prices from $32-41 per barrel in 1980 to mid-1989 levels of $15-20 per barrel, the international energy crisis that followed the 1973 Arab-Israeli war appears to have passed.1 The world has shifted from devising strategies of crisis management to strategies—albeit rapidly fading—for avoiding similar crises in the future. Such were the lessons learned from the sustained energy crisis of the 1970s, which severely affected both the industrialized and developing countries for almost a decade.

For the Western industrialized nations, economic dependency and vulnerability in the hands of a small number of developing countries, mainly in the Islamic Middle East, came as a rude shock. In the crisis, only a radical reevaluation of Western diplomatic and strategic policy in the Middle East could keep the oil flowing to the West.2 Attitudes toward the Arab-Israeli dispute, particularly the Palestinian issue, had to be adjusted in the West—especially in the United States—so as not to alienate the conservative Arab oil-producing states. Whereas few Americans had previously known the difference between Persians and Arabs, or between Shiite and Sunni Muslims, these distinctions were quickly learned. Monarchies such as Iran and Saudi Arabia assumed considerable importance, both as major suppliers of petroleum and as markets for massive sales of military hardware, intended to reverse the flow of petrodollars.

The competition among the industrialized weapons suppliers, especially between Eastern and Western bloc countries, and the sudden accumulation of advanced weapons among oil-exporting countries of the Middle East threatened to upset the military balances that had prevailed among Israel, the conservative and radical Arab states, and Iran. At the same time, the prolonged oil crisis established the economic and strategic interdependence of the Western industrialized countries and the Islamic Middle East. It became clear that conflicts and domestic political upheavals in the Middle East could not be ignored, since every major disturbance implied the threat of a disruption in the oil flow to the West.

The economic consequences for the developing countries were no less severe, although the Western nations had substantially more prosperity at stake. For example, oil demand in the United States in 1973 was 28.61 barrels of oil equivalent per capita, compared with only 1.38 barrels per capita for the Less Developed Countries.3 Nevertheless, in many industrializing countries, such as India, Pakistan, and Brazil, economic shocks from the oil crisis led to severe foreign exchange shortages and the curtailment of various development programs. Unlike wealthy countries, low-and middle-income states were unable or unwilling at the time to trade arms for oil to correct their trade imbalances. (The notable exception is Brazil, which more recently has managed to step up its overseas sales of small arms and ammunition.) Instead, some of these states resorted to other economic tactics. For example, by encouraging unskilled and semiskilled labor to work in the Middle East oil-producing countries, India, Pakistan, South Korea, and Taiwan were partly able to offset the high cost of oil imports through petrodollar remittances from their “export” labor forces. Despite the economic near-catastrophes suffered as a result of the much higher oil prices demanded by the oil-exporting countries of the Middle East, the diplomatic strategy of the developing countries took on an unexpectedly supportive role for the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), in the hope of obtaining special economic concessions and trade and investment benefits.

An offshoot of the 1970s energy crisis was the belief by some of the developing countries that a long-term solution could be found by embarking on or accelerating nuclear energy programs. The dramatic drop in oil prices that began in the mid-1980s has not necessarily reversed the commitment to nuclear energy development in many industrializing states. The choice of this energy alternative, especially by countries with prevailing or perennial security fears—among them India, Pakistan, South Africa, South Korea, and Taiwan—has renewed the concern that resources and capabilities acquired in the nuclear energy sector could make more difficult the control of nuclear weapons proliferation.

While the world in 1989 is no longer in the midst of an energy crisis, it should be clear that there are underlying relationships among (a) a nation’s energy needs and external dependency; (b) its economic and political stability; and (c) its broader security concerns. The intensity of these relationships will, of course, vary from country to country in the developed and developing worlds, and within each country over time. Perhaps in the current framework of an international oil oversupply and low prices, the basic relationships may appear obscure, and “crisis prevention” inappropriate. Much of the new mood of optimism arises from oil discoveries, increases in energy efficiency, especially through advances in computerized automation, and the prospect of tapping alternative energy sources. However, none of these conditions appears to guarantee the longterm resolution of the energy problem. Lessons and legacies forgotten are no less relevant. For example, the rapid consumption of oil discovered in the Gulf of Mexico, the North Sea, and Alaska since 1974 only underlines the inevitable limitations of world oil reserves. Energy conservation through automation also has its limits. While computer technology may fine-tune energy usage in vehicles and buildings, such systems, costly in themselves, can only slow, not halt, the escalating demand for energy. Nor is there yet any clear alternative energy with the exception of atomic power, which in itself constitutes part of the “energy-economy-security” problem.

When dealing with security in the energy context, we are concerned with a broad and an unavoidably subjective connotation of the term. Such a maximalist interpretation encompasses economic, political, strategic, and military security as against the more familiar minimalist interpretation that focuses on military threats and defense programs alone. Economic security thus suggests national resource sufficiency and, in particular, access to goods and services in world markets at affordable terms. Political security suggests the maintenance of domestic stability, whether based on rule by the consent of the governed or on various degrees of authoritarian measures; either way, law and order prevail and economic, political, and social activities are conducted with little or no hindrance. Strategic and military security is partly outward-looking and may be guaged by the degree and intensity of perceived external threats and the military capabilities that can be marshaled to meet those threats. It is also partly inward-looking, in that it involves the diversion of domestic resources and services to meet those threats.

The energy crisis of the 1970s struck at the heart of all three forms of security concerns. For many industrializing countries, including India, Brazil, Pakistan, and South Korea, the periodic spurts in OPEC oil prices produced severe imbalances in foreign trade and severe dislocations in domestic economic plans. Whereas at one time the oil import bill was about 20-30 percent of their export earnings, it quickly rose to some 50-80 percent by the mid-1970s.4 Oil shortages and higher prices hit key economic sectors, including the fertilizer and plastics industries and air and road transportation services. The resulting inflation aggravated these countries’ economic troubles.

Economic crises invariably lead to political instability. As the people of a nation feel the effects of economic stress, they are likely to vent their anger on the government in power, whether democratic or authoritarian. The Indian democracy collapsed with the declaration of the “emergency” between 1975 and 1977 because of economic stresses and public dissatisfaction. On the other hand, authoritarian regimes in South Korea, Pakistan, and Brazil began to feel the pressures of political liberalization and potential revolution as a result of the economic crisis at home.

Strategic and military concerns arise more indirectly as oil exporters accumulate arms either to protect their economic resources and newfound prosperity, or simply because they can afford to buy sophisticated arms with surplus petrodollars, whether needed or not. Security issues arising from the new arms race are complicated by the competition among arms sellers from both the Western and Eastern bloc countries, which results in client military states such as American-backed Saudi Arabia and Iran under the Shah on the one hand, and Soviet-backed Iraq and Libya on the other. Oil importers, especially the advanced industrialized states, may also choose to deploy their military capabilities to protect their international energy sources and supply lines.

Instability may arise not only from new strategic relationships between the regional energy exporters and the internationally powerful energy importers but also from the relationships between developing countries themselves. Many of the new security concerns have been confined to the Middle East and South Asia, for which the oil crisis produced strategic interdependence. The massive purchase of arms from both West and East by oil-exporting states such as Iran, Saudi Arabia, Iraq, and Libya also contributed to the Indo-Pakistani arms race. Concerned about Pakistan’s military links with Saudi Arabia and with the Shah’s Iran, and apprehensive about the general arms buildup in the Middle East and possible arms transfers to Pakistan, India speeded up its decisions on weapons acquisitions from the industrialized states and other decisions on general force modernizations at home.5 The Indian focus on nuclear energy programs also raised the prospect of diversions to a nuclear weapons program and of Pakistani counterresponses to such Indian intentions.

Energy crises, in short, strike at both the economic and defense sectors. Energy policy options among the industrializing countries must, in turn, be adapted or even overhauled to take into account the dual effects on security and the economy, because the balance struck between defense and development programs is tied to fluctuations in the energy market, both at home and abroad. Defense and development programs invariably call for expensive imports of machinery and machine tools, and foreign exchange for such imports is depleted by undue dependence on foreign energy supplies.

The energy factor thus plays a crucial role in the traditional “defense versus development” debate in the industrializing world. This debate usually revolves around the impact of defense expenditures on the national economy or, conversely, how economic conditions affect a nation’s ability to embark on costly defense programs. There are two broad perspectives on the defense-development debate.6 On the one side are those analysts who depict the opportunity costs of defense programs in terms of the development plans of Third World states. On the other side are those analysts who emphasize the spinoffs of defense spending that are favorable for the economy through economies of scale in civilian sectors, mainly the electronics, aerospace, automotive, and shipbuilding sectors. However, the relationship between defense and development as affected by international and domestic energy pressures is seen in the constraints on defense purchases abroad because of depleted foreign exchange reserves, and the constraints on defense procurement at home in a sluggish and unstable economy caused by energy shortages.

In sum, it should be clear that a nation’s energy policy and management carry significant implications for both its security and economic domains. Energy shortages at home require adept diplomacy and adequate bargaining power abroad to fill the breaches. External and internal security, as well as external trade policies and economic development plans, have roots in the successful or unsuccessful management of energy policy. While the international energy crisis may appear to lie behind us, the basic linkages among energy, security, and the economy remain, and energy policy management must aim at either maintaining the present equilibrium or advancing to safer levels. As fossil fuels are rapidly depleted, energy crises will take new forms, and the current search for energy alternatives at home has tended to point to nuclear energy as the potential solution, which in itself poses security problems for the next decade.

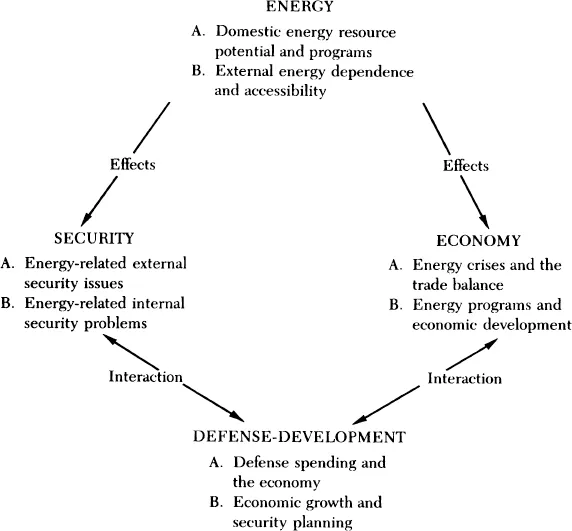

Figure 1.1 delineates the manner in which issues of energy, security, and the economy affect the broader aspects of defense and development planning. Such an analytical approach begins with an assessment of available domestic and external energy resources. Indeed, the degree of a country’s energy surplus, self-sufficiency, or deficiency is the determinant of the other issues of this study. On the supply side, a nation must determine its actual and potential domestic energy resources and then measure them against its actual and potential demand for energy. The shortfall between supply and demand will indicate the degree to which a country must rely on overseas purchases of energy.

External energy dependence raises problems of both accessibility and affordability. The question of accessibility concerns political obstacles that may have to be faced by a country in dealing with energy-exporting countries. Two significant cases are Israel and South Africa. Indeed, the beginning of the Arab oil embargo to the West and the ensuing worldwide oil crisis was provoked by the 1973 Arab-Israeli war and Western policies on the Palestinian issue. Neither Israel nor South Africa has had access to Arab oil at any time in the past, and the fall of the Shah of Iran in 1979 terminated Iranian supplies of oil to both countries. Politically more isolated, South Africa had to rely on purchases from “underground” suppliers that bypassed the international economic sanctions supported by almost all Third World countries, and on alternative domestic sources of energy. India, too, faced some difficulty. Despite its consistent support for the cause of the Palestinians, India had to engage in greater diplomatic maneuvering among the OPEC members of the Middle East than its Islamic neighbor, Pakistan, to ensure the steady supply of oil and oil products. Diplomacy became especially critical after the 1981 outbreak of war between Iran and Iraq, the two countries of the Middle East that had traditionally supplied much of India’s oil imports. Shortfalls had to be supplemented with extensive energy imports from the Soviet Union.

Fig. 1.1. Energy impacts on security and the economy

Similar problems were faced by countries such as Brazil, Argentina, Taiwan, and South Korea, all of which have had to cope with varying degrees of external energy accessibility and affordability. However, supplies from OPEC countries in areas of lower tension than the Middle East—Venezuela, Ecuador, Nigeria, Gambia, and Indonesia—as well as the emergence of Mexico as a major exporter of oil outside the OPEC bloc, helped to temper the political and economic severities of the oil crisis during the crucial 1974-83 decade. In the case of Cuba, which has been more isolated than most other Latin American countries, economic dependence on the Soviet Union was further increased. One of the lessons of the oil crisis era is that political accessibility to overseas sources of energy cannot always be taken for granted.

Economic affordability depends on the importing country’s ability to negotiate favorable prices, or—where such prices are officially nonnegotiable because of the OPEC cartel’s price fixing policies—to negotiate favorable lending and supply terms and to obtain other economic relief. The economic negotiating skills of nearly all of the energy-importing countries are taxed to the fullest in a crisis.

The effects of energy pressures are thus felt both in terms of security and in the economic arena. As delineated in figure 1.1, problems of external security arise from arms races fueled by petrodollars, or from temptations to use military force to resolve some of the repercussions of acute energy shortages that may cripple a country’s economy. Threats to internal security arise from domestic violence or revolutionary movements caused to some degree by energy-related economic dislocations and depressions. In the economic arena, governments must monitor the impact of severe trade imbalances and foreign exchange shortages on development programs if they are to minimize the adverse economic consequences.

The broader relationships among energy, security, and the economy may be considered from two dual, interacting perspectives by each country attempting to resolve the problems arising from these relationships (fig. 1.2). From the first perspective, each state must make two assessments, one relatively objective, the other more subjective: (1) the extent to which it is dependent on...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Lists of Tables and Figures

- 1 The Relationships among Energy, Security, and the Economy

- 2 India

- 3 South Korea

- 4 Pakistan

- 5 Taiwan

- 6 Argentina

- 7 Brazil

- 8 Cuba

- 9 South Africa

- 10 Energy and Security in Industrializing Nations: Prospects for the Future

- Contributors

- Index