This is a test

- 246 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Clinical Orthopedic Examination of a Child

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

It's always been said, "Children are not young adults, " and the examination of a child needs to be conducted with emphasis on the physiologic differences in a growing child. Clinical Orthopedic Examination of a Child focuses on pediatric examination, a topic not much explored in the regular orthopedic texts. A child's difficulty in verbally expressing his symptoms needs to be kept in mind during the examination, thus the examining surgeon has to be very observant in picking up even minor details that could help in diagnosis. This book serves as an essential companion to orthopedic surgeons, general practitioners, and professionals as well as being a welcome addition in pediatric orthopedic clinics.

Key Features

- Reviews an unexplored topic of Pediatric Orthopedic examination with comprehensive clarity

-

- Has an algorithmic approach with step-by-step descriptions, complete with illustrations

-

- Provides helpful tips and insights to orthopedic surgeons, professionals, and trainees for accurate diagnosis and treatment

-

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Clinical Orthopedic Examination of a Child by Nirmal Raj Gopinathan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Medical Theory, Practice & Reference. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Approach to a Child in the Outpatient Clinic

Nirmal Raj Gopinathan

1.1 Introduction

1.2 The Environment

1.3 Communication with the Parents/Caretakers

1.4 Communication with the Child

1.5 The Art of Examining a Child

Bibliography

1.1 Introduction

As is rightly said, clinical examination is an art that every resident/clinician needs to master to be a successful practitioner. The modern advances in diagnostic modalities can neither undermine the importance of clinical examination nor be a substitute for it. The art of examining a child should be entrusted to the trainee from the beginning of residency, as it is imperative to elicit key history and findings that can be easily masked otherwise. The examination of a child needs further training and practice as the comprehensive skills of a child may not match an adult counterpart and the clinician needs to be more talented and capable of picking up minor details. We will cover the basic aspects under four headings, as depicted below.

1.2 The Environment

The examination room must be well lit and child-friendly. It will be of help to have a few puzzles, activities, or cartoon characters painted on the walls of the clinic to create a child-friendly atmosphere. A crowded clinic will not be friendly. It will add to the stranger anxiety and apprehension the child experiences in addition to their pain/suffering, and the clinician will not be able to establish a rapport or examine the child properly. A spacious, less crowded room allows the child to run and play and will provide the examiner an opportunity to observe the child’s activities, motor function, coordination, gait, etc. Avoid wearing a white coat/apron while examining a child. Remember to use a hard couch for examination as a soft mattress may conceal the clinical findings like exaggerated lumbar lordosis in a child with hip flexion contracture.

1.3 Communication with the Parents/Caretakers

The clinician must learn to establish a rapport with the parent and the child, which is the basic minimum requirement of examination. The clinician must give adequate attention to every detail the parents state. Parents constantly observe the child and will be better at picking up even a minor finding or gait abnormality, and the clinician should never ignore their concerns. It is amazing to observe how well a grandparent can give a relevant history or clinical finding that helps in making a diagnosis.

Sit and talk to the parents so that they understand that you are not rushing/hurried, and you are giving adequate time for their child. Try to answer their questions and ease their concerns, which is very helpful in establishing rapport and gaining the trust of the entire family. Try not to dismiss parents’ concerns immediately as it may spoil the relationship. Try to explain in simple language and assure them that few conditions like in-toeing just require observation. Sometimes parents bring recorded activities of the child at home. They can be asked to make a video on their smartphone, which can help to show the characteristic presentation that may not be elicitable in the clinic in the follow-up visit.

Remember that the parents may be stressed due to the multiple opinions given by family members and friends, and they require a warm and comforting conversation. The clinician must also develop a tolerance for the continuous interjections by parents while examining the child instead of losing patience. In cases where the clinician comes across an agitated caretaker or the parents are accusatory, argumentative, or not willing to follow instructions, it is advisable to maintain a calm demeanor and outline the recommendations in a quiet and firm manner.

1.4 Communication with the Child

It is obvious that the child will be anxious and frightened by attending the clinic and being examined by a stranger. It may not be of help to threaten the child, as is commonly said by parents in the clinic – “The doctor is going to give an injection,” which simply increases the child’s apprehension and eliminates the element of cooperation and understanding that can be established. Be friendly and talk to/engage with the child before going to the examination. Be playful and have something like a cartoon character, toy, etc. (do not offer candy as this may be a choking hazard) that can be used to distract a child. Talk to the child about his/her school, friends, teachers, and keep them engaged and distracted. This will also help in establishing a healthy rapport, and the child will start trusting the examiner. A frightened, apprehensive child will not allow a clinical examination, and the entire exercise will be futile and non-informative.

1.5 The Art of Examining a Child

The examination starts by observing the child entering the clinic. The examiner should start examining the child without touching the child or engaging with them. Observe the child’s activity before the examination like walking around, running, trying to climb or hop on a chair, or when a child attempts to play with a revolving chair, which can give you an idea of their coordination and upper and lower extremity function. A child with hemiplegic cerebral palsy (CP) will not sway/swing the involved upper limb in comparison with the normal side. He/she may keep it flexed from the elbow with limited exertion during running. Observe the footwear and its wear characteristics. Observe any kind of orthotics or prosthetics used.

Always examine the child in the presence of parents or guardians as this will make the child comfortable and will avoid unnecessary medicolegal issues. Respect privacy, even if it is a small child. Treat patients and parents with dignity and respect the child’s privacy while undressing the child. Although adequate exposure is required to examine the child properly as a whole, try to cover the genitals and breasts (in an adolescent female). Avoid undressing the child in front of other children and attendants as this will hurt the child’s dignity and self-respect.

Talk to the parents and the child and explain what you are going to do. For example, it is important to explain to the mother of a child with a clubfoot that the manipulations and maneuvers done on the foot are not painful/do not hurt the child. It is important to gain the confidence of both parents and the child to successfully manage the condition. Rub your hands to make them warm and be gentle not to aggravate any pain as the child will try to avoid examination with cold hands or if you start the examination by hurting the child. Do not examine the pathological part first if you believe it is going to hurt. Examine the normal or non-painful side/part first and then gradually drift to the affected side/part, assuring that you will try not to hurt the child. Also, it will be useful to strike up a conversation and distract the child while carrying out the examination. Do not get annoyed if the parents tell you that the other side is affected; explain why you are doing so, which will help you gain their confidence.

Try to avoid words like “pain” and “hurt” while examining the child as these words will increase the child’s apprehension and will spoil an uninterrupted examination. Explain to the parents that some part of the examination may inflict pain and is necessary for diagnosing the disorder. In such circumstances, assure them that you will try to limit the discomfort, which will sound reasonable. Pouncing upon the child for examination will make the parents and the child apprehensive.

Sometimes, the child will be afraid of being examined on an examination couch or especially when you try to position the child prone. In such instances, you may examine the child in the parent’s lap, or you can ask the parent to palpate to help localize the areas that hurt or do simple maneuvers such as elicit passive range of motion and give instructions for an active range of motion examination. Sometimes you may not be able to examine or elicit the findings initially as the child is not consoled and apprehensive. During those times, it is advisable to examine the child later when being fed or when the child sleeps. It is especially important not to assume findings as a result of an inadequate examination. It is also not necessary to get frustrated as not all children are the same and it takes a lot to pacify some of them.

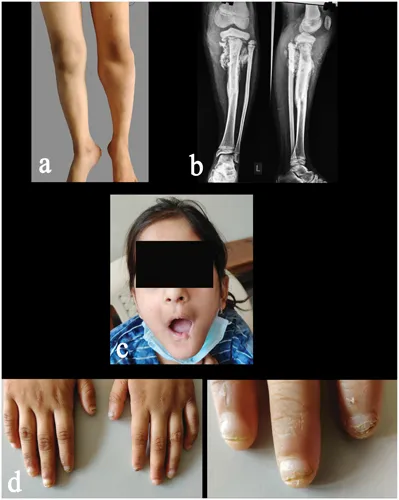

Examine the child as a whole from head to toe. For example, a child with progressive foot deformation may have spinal dysraphism (Figure 1.1), and observing the telltale signs like a tuft of hair in the back will be of help in establishing the diagnosis (Figure 1.2). It is imperative to examine the child from head to toe to avoid missing valuable findings and the time frame in which the conditions can be managed easily. Look for dysmorphic, syndromic, and neurogenic causes and also examine whether the child is hyperlax at the time of presentation (Figures 1.3– 1.5).

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half-Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword I

- Foreword II

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Editor

- Contributors

- 1 Approach to a Child in the Outpatient Clinic

- 2 Biometric Measurements and Normal Growth Parameters in a Child

- 3 Examination of Gait in a Child

- 4 Evaluation of Congenital Limb Deficiencies

- 5 Examination of Pediatric Shoulder

- 6 Examination of Pediatric Elbow

- 7 Examination of Pediatric Hand and Wrist

- 8 Examination of a Child with Birth Brachial Plexus Palsy

- 9 Examination of Hip Joint in a Child

- 10 Examination of Knee Joint in a Child

- 11 Examination of Foot and Ankle in a Child

- 12 Evaluation of the Spine in a Child

- 13 Examination of a Child with Cerebral Palsy

- 14 Peripheral Nerve Examination in a Child

- 15 Evaluation of Swelling/Tumor in a Child

- 16 Evaluation of a Child with Short Stature

- 17 Evaluation of Pediatric Limb Deformities

- 18 Miscellaneous Topics

- Index