![]()

Part I

Assessing the Evidence

![]()

1

Introduction

Knowledge assumed

Principle of energy balance Procedures for testing aerobic fitness, including prediction of maximal oxygen uptake

EARLY OBSERVATIONS

Physical activity and physical fitness have been linked with health and longevity since ancient times. The earliest records of organized exercise used for health promotion are found in China, around 2500 BC. However, it was the Greek physicians of the fifth and early fourth centuries BC who established a tradition of maintaining positive health through ‘regimen’ – the combination of correct eating and exercise. Hippocrates (c.460–370 BC), often called the Father of Modern Medicine, wrote

all parts of the body which have a function, if used in moderation and exercised in labours in which each is accustomed, become thereby healthy, well-developed and age more slowly, but if unused and left idle they become liable to disease, defective in growth and age quickly.

(Jones 1967)

Modern-day exercise research began after the Second World War in the context of post-war aspirations to build a better world. Public health was changing to focus on chronic, non-communicable diseases and the modification of individual behaviour. Whilst Doll and Hill worked on the links between smoking and lung cancer, Professor Jeremy Morris and his colleagues set out to test the hypothesis that deaths from coronary heart disease (CHD) were less common among men engaged in physically active work than among those in sedentary jobs. In seminal papers published in 1953, they reported that conductors working on London’s double-decker buses who climbed around 600 stairs per working day experienced less than half the incidence of heart attacks as the sedentary drivers who sat for 90% of their shift.

Subsequent studies by Morris and others, in particular Morris’ close friend Ralph Paffenbarger in the US, confirmed that the postponement of cardiovascular disease through exercise represents a cause-and-effect relationship. For their contribution, Morris and Paffenbarger were, in 1996, jointly awarded the first International Olympic Medal and Prize for research in exercise sciences.

In the 50 years since Morris’ early papers, research into the influence of physical activity on health has burgeoned. This book is not a comprehensive account of this literature; rather it is an attempt to illustrate its extent, strengths and weaknesses and to help students understand the process of evaluation of evidence. Our emphasis will be on topics that comprise major public health issues. But first, it is necessary to ‘paint a picture’ of some relevant features of today’s societies.

MODERN TRENDS

Just three behaviours – smoking, poor diet and physical inactivity – are the root cause of around one-third of deaths in developed countries. These risk factors often underlie today’s leading chronic disease killers: heart disease, cancer, stroke and diabetes. Sadly, three modern trends will increase the prevalence of these diseases in the twenty-first century. These are the epidemic of obesity, inactivity in children and the increasing age of the population.

Epidemic of obesity

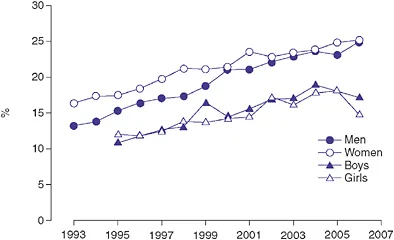

In parts of the world such as North America, the United Kingdom, Eastern Europe and Australasia, obesity prevalence has risen three-fold or more in the last 25 years. Nearly one-third of American adults are obese, and rates in England are the worst in Europe, with 24% of adults obese and a further 38% overweight in 2006, with no real slowing of the upward trend (Figure 1.1). Moreover, all the signs are that the increase in obesity is often faster in developing countries than in the developed world. For example, in South Africa, nearly 60% of black women have been reported to be either obese or overweight. Even in China, where the overall prevalence is below 5%, rates of obesity are almost 20% in some cities.

While the figures for adult obesity give rise to concern, those for children presage an even more major public health problem – perhaps one of the most consequential of the twenty-first century. Serious weight-related problems that may be expected to lead to life-threatening disease in adulthood are already being diagnosed in obese adolescents. In England, 16% of children aged between 2 and 15 were classed as obese in 2006, an increase from 11% in 1995 (Figure 1.1); and in the US almost one in three children and adolescents is either overweight or obese. The problem is global, and increasingly extends into the developing world. For example, in Thailand the prevalence of obesity in 5–12-year-olds rose from 12% to 15% in just two years.

The health hazards of obesity and the ways in which physical activity influences weight regulation are discussed fully in Chapter 6, but one general point will be made here. For many people today, everyday life demands only low levels of physical activity and hence energy expenditure. The average decline in daily energy expenditure in the United Kingdom from the end of the Second World War to 1995 has been estimated

as 3,360 kJ (800 kcal) (James 1995), the equivalent of walking about 16 km (10 miles) less. A large population-based study in which Swedish women recalled retrospectively their daily physical activity at ages 15, 30 and 50 years found a decrease over the last 60 years of the twentieth century equivalent to 45 minutes of brisk walking (approximately 3 miles) (Orsini et al. 2006). The modern phase of the obesity epidemic (from 1980 onwards) is therefore probably mediated more by inactivity than by overeating (Prentice and Jebb 1995).

Inactivity in children

The high prevalence of sedentary behaviours in children and youths partly explains their low total levels of physical activity. In industrialized countries young people typically watch 2–2.5 hours of television each day (Marshall et al. 2006), but in America around 40% of children in some ethnic groups watch at least four hours daily (Andersen et al. 1998). Total ‘screen time’ is even higher among those with access to computers and video/DVD games. For example, Canadian children aged 10–16 are spending, on average, six hours per day in front of a computer or television screen (Health Canada 2007).

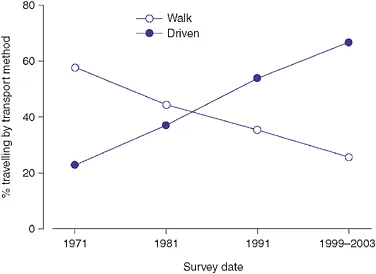

Another factor contributing to low levels of physical activity is the general decline in children’s walking and cycling, and the dramatic decline in physically active transport to school. For example, the percentage of Australian children (aged 5–14) that walked to school halved between 1971 and 1999/2003 (van der Ploeg et al. 2008). The corollary is, of course, that more children are being driven to school (Figure 1.2). In the United Kingdom the number of primary school children travelling to school by

car has doubled in the past 20 years, despite the fact that a majority of these trips are under 1 mile (Black et al. 2001).

Estimates of overall physical activity levels in children world-wide show a marked decline as age increases, with a particularly steep fall in girls. For example, by the age of 15, only 41% of English girls reach the recommended 60 minutes of moderate-intensity activity daily. In Canada – a country long committed to monitoring and increasing physical activity levels – objective pedometer evidence indicates that 91% of children and young people do not meet the guideline of 16,500 steps per day (Health Canada 2007), raising the prospect that self-report (the basis of most descriptive data) may underestimate the extent of inactivity.

Thus the summary by the World Health Organization (WHO) that ‘in many countries, developed and developing, less than ...