- 462 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

The Media Student's Book

About this book

The Media Student's Book is a comprehensive introduction for students of media studies. It covers all the key topics and provides a detailed, lively and accessible guide to concepts and debates.

Now in its fifth edition, this bestselling textbook has been thoroughly revised, re-ordered and updated, with many very recent examples and expanded coverage of the most important issues currently facing media studies. It is structured in three main parts, addressing key concepts, debates, and research skills, methods and resources. Individual chapters include:

- approaching media texts

- narrative

- genres and other classifications

- representations

- globalisation

- ideologies and discourses

- the business of media

- new media in a new world?

- the future of television

- regulation now

- debating advertising, branding and celebrity

- news and its futures

- documentary and 'reality' debates

- from 'audience' to 'users'

- research: skills and methods.

Each chapter includes a range of examples to work with, sometimes as short case studies. They are also supported by separate, longer case studies which include:

- Slumdog Millionaire

- online access for film and music

- CSI and detective fictions

- Let the Right One In and The Orphanage

- PBS, BBC and HBO

- images of migration

- The Age of Stupid and climate change politics.

The authors are experienced in writing, researching and teaching across different levels of undergraduate study, with an awareness of the needs of students. The book is specially designed to be easy and stimulating to use, with:

- a Companion Website with popular chapters from previous editions, extra case studies and further resources for teaching and learning, at: www.mediastudentsbook.com

- margin terms, definitions, photos, references (and even jokes), allied to a comprehensive glossary

- follow-up activities in 'Explore' boxes

- suggestions for further reading and online research

- references and examples from a rich range of media and media forms, including advertising, cinema, games, the internet, magazines, newspapers, photography, radio, and television.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part I

Key concepts

1 Approaching media texts 9 | ||||

Case study: Visual and aural signs 32 | ||||

2 Narratives 42 | ||||

Case study: CSI: Miami and crime fiction 66 | ||||

3 Genres and other classifications 74 | ||||

Case study: Horror as popular art 98 | ||||

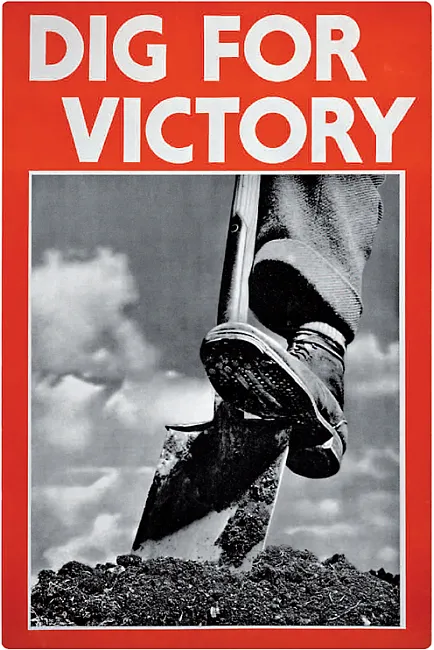

4 Representations 106 | ||||

Case study: Images of migration 129 | ||||

5 Globalisation 138 | ||||

Case study: Slumdog Millionaire: global film? 163 | ||||

6 Ideologies and discourses 172 | ||||

Case study: The Age of Stupid and climate change politics 194 | ||||

7 Media as business 204 | ||||

Case study: Music and movies – digital and available 228 | ||||

1

Approaching media texts

Part of the ‘taken-for-grantedness’ of broadly semiotic or constructionist approaches is media discussions of spin, or PR (public relations). News media often make minute interpretation of signs, debating what a celebrity’s facial expression or a politician’s choice of phrasing ‘really’ signifies. See Chapter 11. |

Roland Barthes (1915–80) French literary theorist, critic and philosopher who applied semiotic analysis to cultural and media forms, famously in Mythologies (1972, originally published 1957), a collection of essays wittily working with ads, wrestling, Greta Garbo’s face and so on. |

Intertextuality: the variety of ways in which media and other texts interact with each other, rather than being unique or distinct. |

Ferdinand de Saussure (1857–1913) French linguist who pioneered the semiotic study of language as a system of signs, organised in ‘codes’ and ‘structures’. The Russian theorist Volosinov, however, suggested the term ‘decoding’ tends to treat language as a dead thing, rather than a living and changing activity. |

Semiotic approaches

The word ‘media’ comes from the Latin word ‘medium’ meaning ‘middle’. ‘Media’ is the plural of this term. |

Semiotics is a theory of signs, and how they work to produce meanings, or the study of how things come to have significance. This includes signs devised to convey meanings (language, badges) as well as ‘symptoms’ (as in ‘that’s the sign of swine flu’). |

Table of contents

- Praise for this new edition

- Praise for previous editions

- Guided tour

- More praise for this new edition

- Student feedback

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Part I Key concepts

- Part II Debates

- Part III Research methods and references

- Glossary of key terms

- Index

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app