![]()

Chapter 1

Shakespeare

First contact

It’s an agreed national ethic that we don’t like Shakespeare. In general knowledge quizzes, the Shakespeare question is left until last and finally approached with a sheepish grin; knowing nothing about Shakespeare is something to be proud of. Children who have never read or seen him groan at the mention of his name. In this respect, Shakespeare is the maths of English. He is also the only compulsory author in the English National Curriculum.

How have we allowed this to happen? Perhaps the first time you saw Shakespeare it was in an elderly, soft covered book. Somebody had written I have never been so Bord (sic) in all my life across the cast list, which contained such promising names as Titania (Queen of the fairies, apparently) and Puck. The teacher handed out the parts to some keen volunteers who read clearly and entirely without understanding for the next six weeks.

First contact with Shakespeare is a highly significant moment for children and deserves some careful planning on your part. This is generally true of openings; schemes of work and individual lessons often live or die in the first few moments.

Transforming your teaching of Shakespeare is easy, and is an object lesson in transforming your teaching in general. Like all teaching successes, it primarily requires thoughtful and focused planning, based on the gifts of the material and its connections with the children.

When considering pupils’ first contact with Shakespeare, there are things you can and should do, and there are things you shouldn’t, and in examining them, we will arrive at some preliminary principles about being a brilliant English teacher.

Don’t show the film first

Of course we want children to see Shakespeare; reading a play anywhere, and especially in a classroom, is an unnatural act, and much work has been done, especially by Rex Gibson, on how to bring Shakespeare to life. But starting with the film is a fatal error.

This isn’t only because there are more bad Shakespeare films than good ones, or because even good ones are still difficult for people new to Shakespeare, but because the biggest ally you have when teaching a text is the story. Children don’t want to spend weeks ploughing through a story when they already know how it ends. This is like watching a recorded football match when you already know the final score.

Don’t choose a play because you love it

It’s a significant principle that you choose teaching material for the pupils, not for yourself. You may have loved Twelfth Night at school, but then you were good at English, and this is a handicap for you now in a number of ways that we will look at later.

For example, many teachers choose a comedy, because adolescents like a good laugh. It’s an understandable decision. But comedy scripts are quite often not funny when read in a classroom. In the case of Shakespeare, the jokes usually have to be analysed. For example, in Twelfth Night, the comic character Feste constantly says things like “Bonos dies, Sir Toby; for as the old hermit of Prague that never saw pen and ink very wittily said to a niece of King Gorboduc: that is, is.” Any joke that has to be explained has already failed. If this is your hilarious secret weapon in selling Shakespeare to Year 9, you’re in trouble.

Many teachers choose Romeo and Juliet because it’s about adolescent love and because some years ago there was a massively popular film and these are good instincts; but be careful. One thing that children new to Shakespeare will often say is “Why doesn’t he just say what he means?” The teacher needs to be able to explain that Shakespeare doesn’t use complex expression (as they see it) just to show off, or to be difficult. For example, a thirteen-year-old coming to this speech of Mercutio’s:

O, then I see Queen Mab hath been with you.

She is the fairies’ midwife, and she comes

In shape no bigger than an agate stone

On the forefinger of an alderman

Drawn with a team of little atomies

Over men’s noses as they lie asleep –

is likely to have his worst fears about Shakespeare confirmed.

Don’t start with context

A lively understanding of context will enrich any study, but in the stage of “first contact” you must above all else be making connections between the pupils and the material. Many children come to Shakespeare with the received attitude that he’s alien, ancient and difficult. Despite the fact that he deals with murder, seduction, incest, prostitution, comedy, war, betrayal, disguise, deception, ambition, sex, cannibalism, jealousy, violence and the supernatural, children know by cultural osmosis that he’s boring. Doing pictures of the Globe theatre or knowing that Juliet, as well as being four hundred years old, was also a boy in tights, will only serve to reinforce the perceived distance and alienness of the text.

Make the connection

I used to work through the plays, with children reading, explaining bits and trying to make it interesting as I went along. They weren’t bad lessons, though I imagine most of the children were quietly bored most of the time. When I started planning with the clear focus of connecting children to the text, my lessons changed dramatically.

Here is an extended example of first contact, in this case between a Year 9 class and A Midsummer Night’s Dream, a very popular play. I’ve set this out in some detail because we can find a number of generic principles and practices that can be adapted for other texts – and not only Shakespearean texts. Although the Dream is a comedy, and frequently chosen for the (in my view highly questionable) reason that children like fairies, I have chosen to focus on non-comedic and non-fairy issues in the play’s opening.

A group of nobles from Athens appears and discusses getting married, or “nuptials”. After some time, more characters arrive and a family dispute is presented to the Duke. In terms of first contact with Shakespeare, this is all quite unpromising. There are fairies in the cast list, which don’t generally impress adolescents; people’s names are unpronounceable or, in a few cases, potentially obscene; and of course the language presents serious difficulties. A simple statement like “our nuptial hour draws on apace” is probably meaningless to most of the children, and this is only the first line of the play.

It is a simple matter to make this first contact something the children will enjoy, remember when they go home, and want to get on with next time. You just have to consider what the point of connection is between the pupils and the text. A girl wants to marry a boy, but her father objects. In fact he prefers another boy. This is in no sense uninteresting to most fourteen-year-olds. Many of them live with this kind of outrageous parental interference on a daily basis. They have opinions about it.

So you have decided on your point of contact, which will highlight issues with which pupils can identify, and about which they will have opinions. Opinions are a major weapon in the brilliant teacher’s armoury, and we will come to them again in later chapters. Adolescents contain large numbers of opinions, and allowing them into your lessons will generate energy and involvement. Pupils are more interested in judging Hermia’s father than in understanding him, and this is the legitimate business of an audience, anyway. So now you just have to construct a lesson that focuses on issues, attitudes and opinions around Hermia’s predicament. From now on the planning is easy. You simply have to provide a structure that focuses where you want to focus. This structure will involve pupil and teacher activity and the editing of the text in order to manage pupils’ first contact with it.

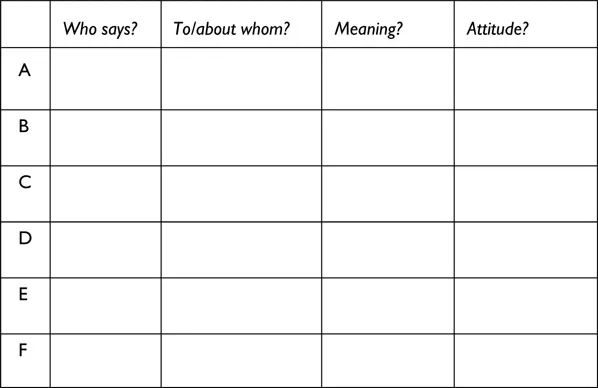

Having made this straightforward planning decision I sat down and made a simple lesson activity. It took me about twenty minutes. What is set out below is a pupils’ activity sheet. They worked on this in pairs. They had no idea that it was connected with Shakespeare; they had not at that point been given the books. The activity is self-contained; you can answer the questions using only the information on the sheet, never having read the play. Try it yourself now.

Table 1.1 There is a problem …

| Theseus is the Duke |

| Egeus is Hermia’s father |

| Hermia loves Lysander |

| Demetrius and Lysander both love Hermia |

| A | This man hath my consent to marry her … |

| B | I would my father look’d but with my eyes! |

| C | … Or else the law of Athens yields you up, Which by no means we may extenuate, To death, or to vow a single life. |

| D | This man hath bewitched the bosom of my child … |

| E | But I beseech your Grace, that I may know The worst that may befall me in this case, If I refuse …? |

| F | You have her father’s love, Demetrius; Let me have Hermia’s; do you marry him! |

| |

This is the central activity, and its objective is to support pupils in understanding a situation and its related attitudes. Let’s consider some key features of this simple activity.

It edits the text

In fact, as editing goes, this is fairly drastic! But in general editing Shakespeare is a good thing. You have never seen a production or read a text that wasn’t edited. Shakespeare can stand editing; reverence isn’t a practical attitude, and Shakespeare is a practical writer. The editing here points at the central focus, obviously; it also presents children with their first contact in the form of tiny, manageable bits of text set into the context of a structured activity. Even so, the text isn’t easy for them; I love Lysander’s joke in F, and I want them to see the comedy there (“I’ll marry the daughter, you can marry the father, he seems quite keen on you!”) because it’s modern, accessible, sarcastic humour, but just the grammatical inversion of do you marry him will make children read it as a question and lose the point. In fact I added the exclamation mark myself to try to avoid this.

It’s structured

As well as being focused on a particular aspect of the text, the activity is structured. The provision of a simple table to complete is powerfully focusing; it generates purpose and concentration.

It’s oral pair work

We need especially here to build confidence, and working in pairs enables pupils to explore and try out different interpretations in an oral arena where things don’t become crystallised too early and where they don’t feel too exposed.

This pair discussion builds to a whole-class version of the family argument and possible solutions to it. But in itself it is not the full picture. As an activity it still needs to be set into the context of the pupils’ experiences. They need to see this family dispute in the context of others.

The personal context

This lesson (and in fact the whole study of the Dream) began with a discussion of family rows. We will talk elsewhere about the openings of lessons, but a sound principle is always to begin concrete; don’t begin abstract. Asking “What do families argue about?” as your opening salvo might work, but it’s a big question, and might simply provoke an uneasy silence as the pupils try to understand what kind of answer you might want. Awkward silences like that at lesson beginnings must be avoided at all costs. They are painfully hard to recover from. There are two tricks to ensure that this doesn’t happen: ask a concrete question (“What was the last family row in your house about?”); and invite two minutes’ jotting before the discussion, so everyone has something to say.

This builds into a whole-class discussion about typical causes of family arguments, and the teacher makes a list of pupil suggestions on the board – bedrooms, food, curfews, and, inevitably, boyfriends and girlfriends. Some anecdotes are exchanged. Some discussion of fair and unfair sanctions is included. This could all take twenty minutes, and is then followed by the There is a problem … sheet.

It’s quite possible that transitions between activities are the most important learning moments in your lesson. When children make the connections themselves, it’s especially rewarding, and strongly indicative that the lesson is going well. In this lesson pupils will often say, as they do the structured activity, “This is like what we were talking about earlier.” You have created a progression (and in fact it’s a constructivist progression), which means that they bring understanding to the text. After the activity, you move on to the text itself, and again they will often see the links for themselves. What you have done is present two layers of warm-up, the first associating the text with their own experiences and so providing confidence as well as engagement, and the second moving everyday themes closer to Shakespeare’s language. Now it’s time to read the text.

People worry about reading Shakespeare, especially when approaching (say) a mixed-ability Year 9 class with their first play. It helps to remember that Shakespeare is the archetypal mixed-ability author. All teachers know that everyone went to Shakespeare’s theatre; in fact, the most expensive seat at the Globe cost thirty times as much as the ch...