This is a test

- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

In an attempt to cope with the profusion of tools and techniques for qualitative methods, texts for students have tended to respond in the following two ways: "how to" or "why to." In contrast, this book takes on both tasks to give students a more complete picture of the field. An Invitation to Qualitative Fieldwork is a helpful guide, a compendium of tips, and a workbook for skills. Whether for a class, as a reference book, or something to return to before, during, and after data-collection, An Invitation to Qualitative Fieldwork is a new kind of qualitative handbook.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access An Invitation to Qualitative Fieldwork by Jason Orne, Michael Bell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Scienze sociali & Antropologia. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

© Matt Raboin

1

The Multilogical Approach

The “job talk” is one of the great rites of academic passage. Candidates spend hours honing what usually represents years of work into a 45 or 50-minute presentation. They worry about what to include. They fuss with the layout of the slides. They stand in front of the mirror trying out different outfits. They practice in front of friends and mentors. They struggle to sleep well the night beforehand.

Mike had endured all that (including the struggle to sleep well). And he had just finished giving the real thing, the actual job talk, at a prestigious East Coast university. He thought the presentation went great. The talk clocked in right on the money at 45 minutes, and Mike made hardly a verbal stumble. So he was feeling good. But nevertheless a little anxious too: The talk was for a position he desperately wanted.

Mike was confident about his argument, drawn from a chapter of his dissertation, an ethnography of the meaning of nature among the residents of an exurban village in England. He thought he had a tight academic case about the relationship between social class and whether villagers thought fox-hunting—a controversial blood sport which the British parliament later banned—was cruel. Middle-class villagers thought fox-hunting was cruel if they were politically left, and thought it wasn’t if they were politically right. Regardless of their party and politics, working-class villagers also thought it was cruel, unless they were (or a close relative was) employed by the fox-hunt. Mike hadn’t found a single exception to these patterns in his fieldwork, which supported the larger theoretical point he was trying to establish about how ideas of nature reflected social ideas.

Mike put down his notes, flashed a smile at the classroom of professors and students, and asked, “Are there any questions?”

Immediately, a hand went up in the back corner of the room.

“Yes?” Mike invited.

A grey-haired man wearing a tweed blazer lumbered to his feet.

(“Uh-oh,” thought Mike.)

“Mister Bell,” began the grey-haired man.

(“‘Mister Bell’? Uh-oh for sure … .”)

“I have only one question for you. In what way would you distinguish your work from fiction?”

Needless to say, Mike didn’t get that job. He did get an academic job eventually (and even published his dissertation at an academic press).1 Otherwise we probably would not have been given the chance to write this book. We also would not have written it if stories like this—stories that show a continuing doubt in some quarters about qualitative fieldwork methods and a corresponding defensiveness among its practitioners— weren’t still so common.2 The situation has much improved in our own field, sociology, since Mike gave that ill-fated talk in 1992. Qualitative fieldwork is now regularly accepted in most of the leading sociology journals and a sociology department with no qualitative methodologists would be considered odd. Geography and education departments are also now generally welcoming of qualitative fieldwork and anthropology always has been. The situation remains more mixed, however, in political science, economics, business, psychology, and the health sciences.

We offer this book to aspiring qualitative fieldworkers in all fields. We offer it both to those seeking to improve their understanding and practice of qualitative fieldwork and to those seeking to persuade others of its value. We offer it, too, as a new synthesis of qualitative fieldwork as a contextual science* attuned to the multiple logics of any instance of social life—and the relations, interactions, constraints, histories, regularities, and creative surprises that shape these logics and that these logics afford.

Contextuality and Intercontextuality

Consider the context of Mike’s ill-fated job talk. The meanings and consequences of Mike’s talk were highly contingent on how those in the room understood it—on the logic (really, the logics) they brought to bear on the talk and how the context of the talk encouraged or discouraged various logics for evaluating it. Most obviously, the talk’s success depended in part on how well Mike met the standards of academic performance. Did he speak well? Did he dress well? Were the slides nicely done? Was there an appropriate mix of theory and evidence? Did he clearly connect the work to important academic questions and literatures? Did it seem to offer something new?

But given that Mike did eventually get a job using this same talk (albeit with a few modifications), we can assume the relative success of the talk was not contingent on Mike’s performance alone. Other logics also danced around in the context. Not necessarily logical logics, however—at least from Mike’s point of view! The logicalness of any particular logic in our multi-logical world is something we may all have different opinions about. At the very least, the grey-haired man understood the talk quite differently from how Mike did.

Fortunately, although that questioner did not trust Mike’s ethnography, many others did. No one else asked him a direct question like that (thankfully, says Mike). He did get many other questions, of course, each one a consequence of how someone understood what Mike had presented and why they were attending his talk. Graduate students who were pondering their own future job talks responded differently than faculty members with votes in the selection process. Undergraduates attending for extra credit points in a course took it differently again. Everyone brings at least a different logic to a situation. There were as well differences of subdisciplinary interest, theoretical predilection, and personal political views. Given our usual social concern for matters of gender, sexuality, class, race, age, looks, and so much more, audience members probably also considered Mike’s presentation in light of how they identified themselves and how they identified Mike with regard to these characteristics, even if subconsciously. More logics yet.

But these varying reactions did also depend upon Mike. People from different universities were responding to what he—a wavy-haired white male then in his early thirties, exhibiting the class competencies of many years of university training—said about a topic not commonly dissected by American academics: British fox-hunting. Likely, most people in those lecture rooms had never heard a talk on British fox-hunting—and assuredly not one delivered by Mike. These talks were situations that the people in them had never exactly encountered before, as familiar as most features of these situations no doubt were to them. And they responded to them in ways that differed at least a little bit from how they had responded to other talks they had experienced.

What everyday evidence like these varying reactions suggest to the qualitative fieldworker is that different people in different situations will understand differently and accordingly act differently. It also suggests that different people in the same situation will understand and act differently. We should put the matter more strongly: No one situation is ever the same for everyone in it, because of our differences.

Let’s get this down as tightly as we can. One situation, many logics. Many situations, many, many logics.

In short, when we speak of context in this book, we don’t mean uniformity of experience for all concerned. Nor do we mean that those in a context are leaves passively floating along a stream of social life. (Mike’s questioner definitely diverted the flow of events.) People shape context and are shaped by it—a two-way effect we call the contextuality of a social situation.

Contextuality is infinitely complex—and we do mean “infinitely.” We have only been scratching at the surface of understandings and actions elicited by, and involved in, Mike’s job talks that year. Yes, it was all university people in university settings engaged in a familiar kind of university event. But the people involved had different histories, different concerns, different positions within the event. And while his particular job talk was much the same as any other (or people would not have recognized it as a job talk), it was also unlike any other. Indeed, if it had been exactly the same, and if everyone in it had responded in exactly the same way, those involved would probably have been deeply disturbed and questioned their own sanity. Life isn’t like that.

So contextuality is not constancy. Not only does any one context contain potentially huge diversity within it, no one context is ever completely the same as another. Thus, given the variation and complexity of real life, a complete rendering of contexuality is beyond what science can achieve. Perhaps it would be theoretically possible to render it completely, but practically speaking it could not be done.

Indeed, a strong case could be made that a complete rendering of contextuality is actually theoretically impossible—especially when we consider an event of far more consequence to far more people than Mike’s talk so many years ago.

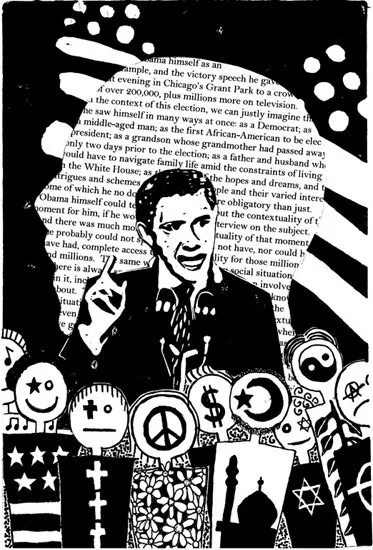

Consider the many meanings involved in the election of Barack Hussein Obama on November 4, 2008 to the office of President of the United States. Nearly 130 million people voted in that election. Many were overjoyed with the result. And many were not. Their reasons for approval or disapproval varied widely. Moreover, Obama’s election had many meanings for most people involved in its context—not just one meaning per person, as our surface scratching up above perhaps implied. No doubt some meanings were more consequential than others for each person, but each still experienced a multitude.

Take Obama himself and the victory speech he gave that evening in Chicago’s Grant Park to a crowd of over 200,000, plus millions more on television. Obama likely saw himself in many ways at once. As a Democrat. As a former US senator. As a middle-aged man. As the first African-American to be elected president. As a grandson whose grandmother had passed only two days prior to the election. As a father and husband who would have to navigate family life amid the constraints of the White House. As the bearer of the hopes and dreams—and the intrigues and schemes—of millions and millions of people, many of which he did not personally support, given the inevitable compromises of building a political coalition.

Obama himself could tell us much more about the contextuality of that moment for him if he would consent to an interview on the subject. And there was much about the contextuality of that moment he probably could not speak to, for he did not have, nor could not have had, complete access to its contextuality for those millions and millions. The same would be true of any social situation: There is always so much going on for every person involved in it, including much that they do not understand or know about.

One person, one situation, many logics.

Moreover, a person’s involvements actually extend beyond any one situation, making a complete rendering of contextuality even more difficult. For we bring our lives with us wherever we go. What we do in any one place and moment has implications that stretch elsewhere and else when. The significance of a context lies in how it matters for more than that one spot in the continuum of space and time. Otherwise, why be bothered about what goes on in it?

Just as importantly, what happens in other situations far away in space and time shapes what happens in the situations of our own little struggles and enjoyments. Any one context almost always—and maybe really and truly always—has consequence for another.

In this book we refer to this interdependent consequence of context as intercontextuality, the connection any one context has to many others. A contextual science must also be an intercontextual science, looking at the bigger in the smaller and the smaller in the bigger—or, to use terms often favored by social theorists, looking at the macro in the micro and the micro in the macro.

Take Obama’s gender. As historic as his victory was from the perspective of race relations in the US, there was nothing novel in him becoming the 44th man in a row to be elected president. One would not have to be a deep student of social life to recognize that there is a long social history of assumptions and privileges associated with the distinctions we make between men and women, not least with regard to politics and power. The context of masculinity and patriarchy came into that speech at Grant Park and went on beyond it, reinforcing some presumptions about gender but also opening up others, given that Obama’s main primary challenger had been a woman, Hilary Rodham Clinton—but a woman who had gained prominence to a significant degree because of her husband, President Bill Clinton.

Which is all a long way round to say that a social situation has a lot more going on than immediately meets the eye, and its implications extend from one situation to the next, ever varying and ever connecting.

A Multilogical Method for a Multilogical World

Researchers often seek a more unified and stable image of the empirical world than we have been describing here. But qualitative fieldwork typically does not yield such confidence—although not because of any necessary lack of accuracy. Rather, the closeness and detail of qualitative fieldwork give researchers a deep appreciation of the complications and contradictions of real social life. Thus, while the qualitative fieldworker seeks to understand the interdependent consequences of context, she or he does not imagine a seamless world that is all one vast weave of threads, webs, or wires. Social life is not The Matrix. There is no single Architect or Source, no unified master logic to which all must comply, aside from the occasional Anomaly. There are indeed important connections across space and time, as one context intercontextually reaches into others. We very much need to understand these connections, which we often have trouble seeing from the perspective of an individual life or locality. But the social is also replete with differences, conflicts, disconnections, and resistances. We need to pay equal attention to these disjunctures, and not necessarily with an eye to eliminating them or folding them into an ever-grander theory of everything. Very often it is the disjunctures which give us hope and opportunity, not merely dismay and confusion.3

Let’s take another look at Obama’s 2008 victory speech. His election was, of course, vigorously contested by his challenger, Senator John McCain. Although Obama won 68 percent of the Electoral College, the US’s singular means of tabulating votes state by state, he received less than 53 percent of the popular vote. This outcome was far from clear over the course of the campaign. Only three months before the election, national polls had shown McCain with a ten-point lead. Both sides had reason to hope and both sides saw opportunity. Each side tried tactics that had not been used before. The Obama campaign used social media such as MySpace and Facebook that had barely even existed in the previous presidential election, raising an unprecedented level of contributions from small donors. John McCain chose as his running mate the first woman Republican vice presidential candidate, Governor Sarah Palin. Despite the increasing precision and frequency of polls, no one really knew how it would turn out until close to the end. There were simply too many...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Other Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents in Brief

- Contents in Detail

- Preface

- 1 The Multilogical Approach

- Ways of Relating

- Ways of Gathering

- Ways of Telling

- Notes

- References

- Glossary Index