All of us now live in a world of media on demand. We receive the news we want, how and when we want it, in whatever degree of depth we prefer, on the devices of our choice. In the days of traditional mass media, when there were few ways to learn about news, information was published and broadcast with the idea that the audiences who needed it would seek it out. Households subscribed to daily newspapers. Commuters listened to drive-time FM radio in their cars on their way to and from work. Families tuned in to six o’clock and eleven o’clock local news broadcasts. With the advent of a public Internet, new mobile technology, and to some degree years earlier, the non-legacy news outlets created in the early days of cable TV (specifically CNN, and later, CNN’s Headline News, which introduced the twenty-four-hour news cycle), viewers were liberated from the fixed time slots and delivery methods of the old mass media model. Although in the pre-Internet days of the early 1980s, the kind of multimedia journalism we think of today was not possible, CNN’s cable news experiment was among the first to change the viewer’s relationship to the media. More significant changes evolved slowly with the development of cable and satellite television, and the proliferation of channels throughout the 1980s.

Beginning in the 1990s, widespread Internet access made convergent journalism truly possible for the first time by allowing the Web to serve as a new platform for the dissemination of news and information that was accessible to consumers on their own schedules. The Web-based news model did two important things: It allowed news consumers to pick and choose which stories they wanted to follow and in how much depth, and it freed consumers from the limitations of TV time slots and newspaper press deadlines. It was not quite yet what we now think of as news on demand, but it was a radical departure from the traditional mass media model.

Convergent journalism has come of age. It is now at a point of maturation. Indeed, most news has been converged for years. Most print and broadcast outlets have websites and blogs. Many routinely post photos, videos, and slideshows. Some boast podcasts. Others host live online events. Most are active on social media. Some even curate social media content, occasionally covering breaking stories half a world away. This is good news for those with roots in traditional journalism who lament the end of the field as they know it. The truth is that the only people predicting the end of journalism are those still living in a pre-converged world—which is to say not many. Thanks to smartphones and the global networks that connect them, even the developing world is quickly converging. Passionate, dedicated journalists adapt and learn the new tools and practices instead of mourning the old ways. In fact, flexibility and the desire to perpetually retrain to stay on top of the latest changes and developments in technology may be the single most important characteristic of an entrepreneurial journalist.

How we Got here

Journalism’s professional orientation has long united its practitioners and students. Journalism is rare among academic disciplines in that it, in a way perhaps similar to forensics (debate) and sports programs, allows students ample opportunities for real world practice while still enrolled in college. There are few collegiate activities outside of sports that routinely send enthusiastic students to conferences and trade shows. Anyone harboring doubts about the future of journalism need only attend a college journalism conference to have their faith renewed for good.

Journalism has always been more than a job for those who do it. Journalists share a strong culture. Until the 1970s, journalism ran like a medieval guild where young men who started as copy boys rose slowly through the ranks over years to become reporters, editors or copy chiefs. The vast majority of reporters were male and lacked formal education. They learned on the job by immersing themselves in their news beat over decades. This now-obsolete model of the hard-bitten journalist was similar to Raymond Chandleresque gumshoe stereotypes.

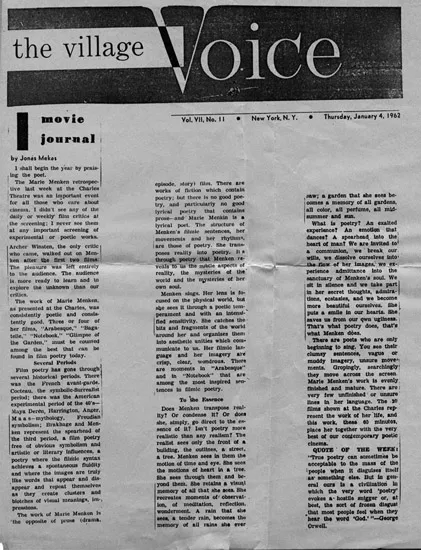

Figure 1.2 The Village Voice remains the first and most famous alternative newsweekly. Photo by Bigjoe5216 / Wikimedia Commons.

The image of the hard-drinking, hard-living journalist who made his bones by becoming a political insider with connections across the city began to fade in the mid-1950s, with the advent of the alternative press. The earliest and still best-known alternative newspaper is New York’s Village Voice, a weekly tabloid that covered the counterculture that was beginning to coalesce (at least in large coastal cities) during Eisenhower’s famously conservative postwar 1950s. For the first time in hundreds of years, the alternative press changed the newspaper’s business model by running the kinds of advertisements the mainstream dailies refused to print—mostly for pornography and prostitution (advertised as escort services or massage parlors). Although the Voice initially charged a cover price, it eventually sold enough ads to support the distribution of copies throughout New York City for free. Other alternative weekly newspapers ultimately followed the Voice’s lead and offered free circulation instead of paid subscriptions. Circulation continued to grow as newspaper companies installed honor boxes (which allowed readers to take copies without putting coins in a slot) on city sidewalks alongside the dailies’ coin-operated boxes. As young people started moving back to the cities following the suburban exodus of the middle class in the postwar years, alternative weeklies enjoyed a surge in readership and popularity. By the 1990s alternative weeklies had themselves become the mainstream, largely eschewing the kind of extensive investigative reporting they had become famous for a generation earlier in favor of expanded arts and entertainment coverage, and lifestyle features. Instead of picking up the paper to read about political corruption or pressing social issues, most people browsed alt weeklies for their extensive events calendars, arts reviews, and movie times listings. Although they did not much resemble Voice co-founder Norman Mailer’s vision for alternative journalism, the weeklies were selling ads and doing well through the 1990s. But the alt weekly renaissance would also ultimately end.

For the alternative press, the end began with an early Web browser called Netscape and the funny-sounding search engine Yahoo! Within a few years, Craig-slist, a peer-to-peer online marketplace, went national, and soon those ads for pornography and prostitution that had previously been the exclusive domain of alt weeklies began moving online. In 2000, when Craigslist expanded nationally from its local San Francisco Bay Area home, the ad-supported alternative weekly business model began to falter. It would take several years for alt weeklies to feel the full effect of Craigslist’s classified domination, but eventually, just like their peers at daily newspapers, journalists working at weeklies began expressing legitimate worry about their futures. It was at this time that talk of alternative models not just for reporting news but also for financing it emerged. At first hope came from strange places—namely philanthropists.

Although it would be decades until the converged newsroom would become a reality, way back in 1975 an old-time Florida newspaperman known for his starched white oxford shirts and natty bowties changed the future of journalism in ways he could never have imagined at the time of his death in 1978. Nelson Poynter’s legacy, now known as the Poynter Institute, began its existence as Modern Media Institute, a school for journalists that owned controlling stock in Poynter’s St. Petersburg Times Company, which publishes the Tampa Bay Times. Poynter’s dream was two-fold. Not only did he want to protect his newspaper from marketplace demands, but he wanted to help train working journalists to improve their craft.1

Poynter’s experiment has endured, enjoying years of success as a training ground for journalists. Today, the Poynter Institute and its extensive website Poynter.org are among the best-known resources in journalism. Every day new and experienced journalists turn to Poynter for onsite and online training, webinars, tutorials, news, tips, and job leads. After years in the spotlight and consistent Pulitzer Prizes, the future may not be so bright for the Tampa Bay Times, which remains one of few news entities owned by a nonprofit organization. Toward the end of 2014, high-profile media blogger (formerly for Poynter.org) Jim Romenesko wrote about the Times’ precarious finances. Quoting from an email he received from an anonymous staffer, Romenesko blogged about a “crisis situation” in which the paper was “on the brink of doom” over financial shortfalls.2

Although the Times’ unusual business model remained a curiosity for the first couple decades after Poynter’s death, it became a topic of serious consideration in the early years of the millennium, when those in the news business started seriously looking at alternative business models to keep print journalism alive. “[B]eleaguered industry veterans longingly turn their collective gaze to the Times and Poynter for inspiration,” Times veteran Louis Hau wrote in Forbes in late 2006.3 At around the time of the Forbes article, desperation over the decline of the traditional for-profit newspaper model led some to cling to the nonprofit model like a lifeboat. But the news industry was about to become much more complicated. Soon it was not just the business model but the platform itself that would undergo unprecedented change.

By 2005 the concept of the “Web-first” newsroom had taken hold in traditional newspaper offices everywhere. The radical new idea—that instead of an online regurgitation of the exact contents of the print edition, a newspaper’s stories would break on the paper’s website, then get the full treatment in print—was not winning over many fans. The paper’s writers and editors remained convinced that print contained the paper’s most exclusive real estate, and that no one would go online to read a story that was also available in print. In this pre-smartphone era with the introduction of Apple’s first iPhone still a couple years off, few used mobile devices to access the Internet, and no one used them to read newspaper stories. But newspaper and magazine publishers were becoming increasingly aware of the need to publish online. The big question was what to publish. Breaking news stories such as trial coverage opened the door to a new kind of reporting, as journalists were for the first time free of rigid deadline pressures and were newly liberated to post content before an editor could read it. This simple alteration in workflow flipped the newsroom power dynamic. Writers and reporters rejoiced while editors wondered how they could maintain quality control (or simply control) in the twenty-four-hour newsroom.

At the Philadelphia Weekly, an alternative weekly newspaper, the move online was straightforward. Like at many newspapers and magazines in the early days of online publication, the exact conten...